12. Lean and Other Cost-Reduction Strategies in Supply Chain Management

12.1.3 Other Cost Management Tools

12.2 Lean Supply Chain Management Principles

12.2.1 Seek Leadership and Growth Strategy

12.2.2 Seek a Strategic Customer Value Focus

12.2.3 Seek Single Source and Reliable Suppliers

12.2.4 Seek to Build Trust Based Alliances with Ethical Supply Chain Partners

12.2.5 Seek a Demand Pull, Synchronized Supply Chain

12.2.6 Seek to Maximize Flow and Eliminate Supply Chain Flow Constraints

12.2.7 Seek Supply Chain Agility

12.2.8 Seek Continuous Improvement

12.2.9 Seek Reduced Cost Through Waste Elimination

12.3 Other Cost-Reduction Strategies

12.3.1 Procurement Partner Competition

12.3.2 Standardization and Commoditization

12.3.3 Combined Organization and Opportunity Analyses Cost Strategy

12.4 Other Topics in Lean and Other Cost-Reduction Strategies in Supply Chain Management

12.4.1 Transforming Lean Procurement Principles in Service Organizations

12.4.2 Mistakes in Lean Implementation

12.4.3 Collaboration as a Cost-Reduction Strategy

Terms

Computerized maintenance management system (CMMS)

Lean supply chain productivity cycling process

Mixed model scheduling

12.1. Prerequisite Material

12.1.1. Cost Management

Cost minimization is one the primary functions of supply chain managers and operation managers in general. To aid in accomplishing this task, firms often establish a cost management program. Cost management is an ongoing process of managing the uses of an organization’s funds to minimize the cost of operations. A cost management program involves an ongoing planning and cost estimating process for projects and programs, budgeting costs for the firm as a whole, and controlling costs. This is a broad topic that impacts planning in all functional areas within a firm. A detailed discussion of this subject is beyond the scope of this book and is not the focus of this chapter (which is, instead, on cost strategies). For a detailed discussion on cost management, see Carter and Choi (2008, pp. 44–79).

While cost management is a continuous program, many applications of cost management projects are undertaken in supply chain departments. Typically for supply chain organizations, cost management is used to support a larger cost-reduction strategy. To accomplish this, a cost-reduction team is established whose role is to seek out and find areas in the supply chain department cost structure that can be reduced (Fawcett et al., 2007, p. 445). The composition of this team is similar to as a cross-functional team (see Chapter 10, “Developing Partnerships in Supply Chains”). The focus here is on identifying cost-reduction areas and tactics on projects, processes, policies, and practices. To accomplish cost-reduction goals, a cost driver analysis is often undertaken.

12.1.2. Cost Driver Analysis

To reduce costs in a firm, a cost-reduction team needs to identify what drives costs. A cost driver analysis determines the processes, activities, and decisions that actually result in supply chains costs (Fawcett et al., 2007, p. 251). Cost drivers can be unique to a product or practice. For example, a cost driver might be the amount of inventory a firm is willing to permit. An excess of finished inventory increases or drives up the costs of insurance, taxes, handling, and so on, but it provides a quick response to customer demand surges in highly volatile markets. Also, excess logistics equipment such as trucks can drive up capital expenditure costs, maintenance costs, obsolescence costs, and so on, but excess transportation equipment might be beneficial in volatile transportation situations where a firm might possibly have to outsource their trucking needs. In such situations, shortage of availability might be very expensive.

Cost analysis can include the following elements (Carter and Choi, 2008, p. 37):

• Determine the competitive structure of the industry (for example, highly competitive market situation with lower costs for services or higher costs in a monopolistic economic environment).

• Determine the market structure (for example, international or domestic).

• Determine cost drivers and supplier pricing trends.

• Determine the cost impact of other trends (for example, changes in technology, new processes.).

Ideally, cost analysis will indicate what reasonable costs (or prices paid to a supplier) should be in terms of the market, industry, supplier’s cost structure, and the client organization’s needs.

12.1.3. Other Cost Management Tools

To support cost analysis efforts in cost management, a number of analyses are available. Other tools useful in cost management include the following (Fawcett et al., 2007, p. 254, Carter and Choi, 2008, pp. 60–62; Wincel, 2004, pp. 162–178):

• Price analysis: Price analysis is a comparative study of item prices in the market. It is used to help understand price availability in a competitive marketplace.

• Total cost of ownership: Total cost of ownership (TOC) seeks to determine the total cost of acquisition, use, maintenance, and environmental disposal of products, processes, and equipment. It is used to determine the true total costs of an item (see Carter and Choi, 2008, pp. 54–58).

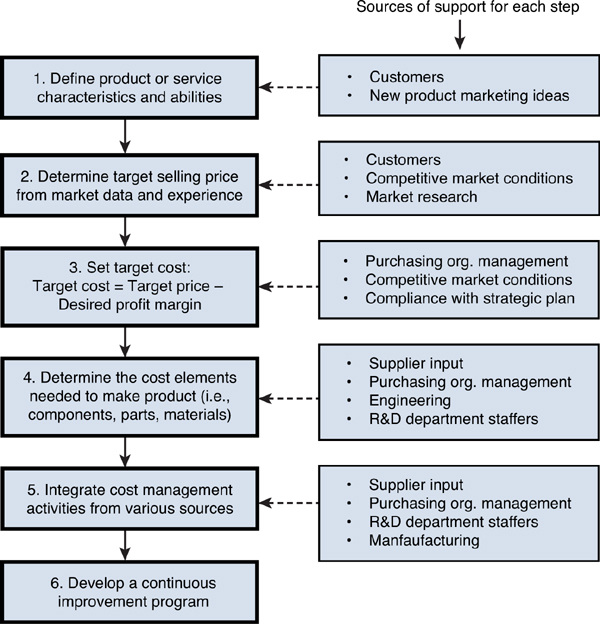

• Target costing: Target costing is a methodology that seeks to establish a fair price for a product by starting with the product’s estimated costs and what a firm expects in terms of profit. It figures existing market prices for supplier provided goods and services, then works backward, determining what a purchasing firm can afford to produce, while still making a profit. The steps in a target costing process are presented in Figure 12.1.

Figure 12.1. Steps in a target costing process

Source: Adapted from Ellram (1999); Matthews and Stanley (2008, Figure 3-8, p. 94).

• Cost control and improvement: This specifically identifies the annual price improvement and cost-reduction tasks consistent with industry and commodity conditions. It employs short- and long-term efforts to find opportunities that can be benchmarked against industry practices and uses collaboration with suppliers to improve agreements.

• Value management: Value management (VM) can be defined as a collection of various efforts to capture and retain improvements at each step in the value chain of a supply chain. It determines the entire supply chain value stream cost elements to identify cost opportunities. It provides valued added workshops to facilitate the identification of design-based savings and institutionalize VM data collection methods to aid in supplier/purchaser cost-reduction strategies.

• Supply chain process improvement: This introduces process improvement techniques to the supply network and creates an institutionalized process improvement focus. It includes cost control methods and utilizes modeling of the supplier network to explore and implement cost-reduction strategies.

To guide any of the cost management program and analyses mentioned here, a firm must determine an overall cost strategy. There are many different cost strategies. Some are focused on limited areas in a supply chain, and others are global, covering an organization’s overall approach or guiding philosophy of operations. One global strategy that has developed into a field of management is lean management.

12.1.4. Lean Management

Lean management involves the use of a set of principles, approaches, and methodologies that can be applied individually or collectively to guide organizations toward world-class performance. Lean can be implemented as a process, project, program, principle, approach, methodology, or philosophy. It can be applied to individual processes, individual departments or entire organizations as a project for short-term efficiency improvements or extended, longer-term programs, where projects are undertaken to permanently install lean for continuous process improvement.

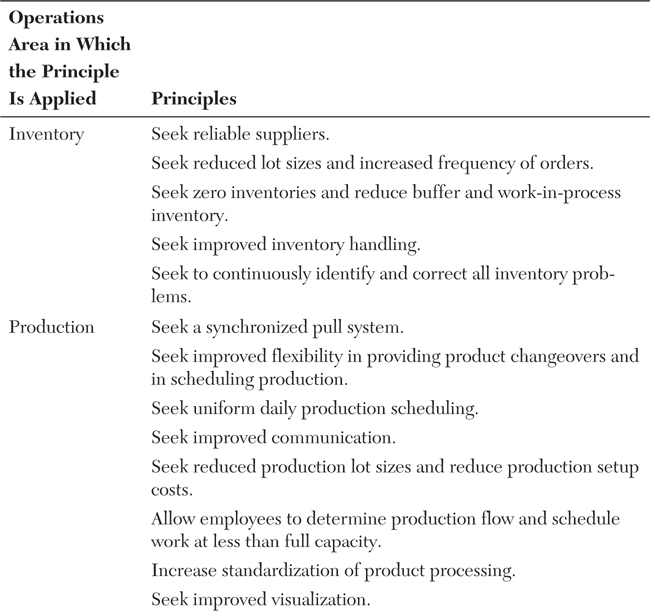

Lean management applies a series principles used to eliminate waste of all kinds that rob efficiency and add needless cost to operations. By eliminating waste, the respective operating costs are reduced. Some of the lean management principles are presented in Table 12.1. These and other lean management principles were originally developed by the Toyota Corporation as a program to improve efficiency by eliminating waste in its production system. The principles have evolved through contributions from scholars and practitioners to be the most commonly known cost management strategy. The principles have also been adapted for use in supply chain management (Wincel, 2004; Kerber and Dreckshage; 2011, Schniederjans et al., 2010; Zylstra, 2006).

Table 12.1. Lean Management Principles

Topics in lean management have been a dominant cost-reduction strategy for decades (Schonberger, 1982). Their subsequent use in supply chains (Wincel, 2004) as a best practice (Blanchard, 2007, pp. 95–97) has become second nature for most supply chain managers. Therefore, its coverage as a cost-reduction strategy can be viewed as mandatory in any supply chain book exploring cost-reduction strategies.

12.2. Lean Supply Chain Management Principles

A lean supply chain is one where there exists no waste and no inefficiencies. Few supply chains ever fully implement all the principles of lean management to actually eliminate all waste and inefficiencies. Seeking a lean supply chain should simply be viewed as a strategic cost-reduction goal that is continuously sought under a lean supply chain management program. To operationalize a lean supply chain management program requires the application of lean management principles within the context of a firm’s supply chain.

Lean supply chain management principles are derived from a larger set of lean management principles dealing with broader operations management areas of responsibility (for example, inventory, production, human resources, quality, and facility design). As such, the applicability of these principles to supply chain management includes a broader management perspective that impacts all areas of operations management.

The following subsections cover a number of select lean supply chain management principles that can be used collectively as a cost-reduction strategy.

12.2.1. Seek Leadership and Growth Strategy

A lean supply chain project or program requires a driving force of effort from a leader for implementation (Dolcemascolo, 2006). For firms that focus on their supply chain as a strategy for competitive advantage, the creation of an upper-level organizational position such as vice president of supply chain management should be a requirement. In addition, supply chain executive training sessions on lean supply chain ideas should be undertaken to help managers develop into lean leaders who champion, promote, and motivate the implementation of lean principles within a firm’s supply chain (Martin, 2007). Reflecting the support of upper management for a lean supply chain, a champion might also use lean training, problem solving, and other groupings to help champion the use of lean principles within the firm’s supply chain. Successful leaders avoid waste in organizational change by giving direction and improving the efficiency of change by coordinating the steps toward a lean supply chain.

12.2.2. Seek a Strategic Customer Value Focus

Focusing on customer needs is a driving force in all supply chains (Christopher, 2011, pp. 6–7). Communication and Internet technologies have empowered customers to use global markets to acquire products and services; so in turn, firms must compete in those global markets. One of the main ways to be successful in such a competitive environment is to offer customers greater need satisfaction opportunities than other firms. This is achieved in a lean supply chain by having lean principles directly impact the value given by the product (for example, enhanced product or service quality, reduced costs) and having the supply chain provide exceptional (for example, quick response) delivery. Lean supply chain management can generate value and become a competitive advantage for firms that utilize its synergy (see value proposition in Chapter 1, Section 1.6).

12.2.3. Seek Single-Source and Reliable Suppliers

Having fewer but reliable supply chain suppliers reduces administrative costs (as compared to having a larger numbers of suppliers). Moreover, a smaller number of suppliers should be able to provide quicker responses, because both partners are more familiar with each other due to increased frequency of contact (that is, a greater amount of ordering per supplier will occur because there are fewer suppliers in the network) (Mangan et al., 2008). When a firm has only one or a small number of suppliers, the purchasing organization is more dependent on them, resulting in a greater need for supplier reliability. That dependency should be a shared concern of the suppliers because they realize failure to deliver a product or service can be disastrous for the client firm. In some situations, this puts psychological pressure on the supplier to do the job right every time. Supplier reliability might also include timely communications and responsiveness of the supplier to solve problems and meet customer demand issues. Reliability also works both ways in lean supply chain management. Purchasing firms should seek to establish long-term contractual relationships with suppliers to assure them of continual support and future business (Martin, 2008).

12.2.4. Seek to Build Trust Based Alliances with Ethical Supply Chain Partners

One of the most common approaches for developing trust in supply chain partners is for all partners to maintain high ethical standards in all business activities and behaviors. If the suppliers observe the purchasing firm in a supply chain seeks to maintain ethical values of fair play, they may come to understand and habitually act in a similarly ethical manner toward the client firm. Even in fairly short-term transactional or supply chain alliances with suppliers, the notion that a client firm conducts business in an ethical way helps to establish an implied standard operating procedure of ethical conduct.

Ethical conduct can help avoid waste and save time and money. For example, the unethical conduct of suppliers sending knowingly poor quality goods will waste time and result in wasteful costs of scrapping goods, reprocessing them, or returning the items. One of the lessons of lean management principles is that establishing an atmosphere in supply chains that seeks to build trust and empowers members will aid trust building and foster pride throughout the supply chain. To implement this kind of environment, the lean supply chain principle suggests that the contracts should include compensation plans that reward supply chain partners for ethical conduct efforts. Part of those efforts should be to work toward building trust by bringing suppliers together to work in teams on problem solving. Working together while displaying ethical conduct and seeing how each can help the supply chain as a whole will build trust among members.

Another lean supply chain tactic for building trust is to offer long-term contracts to supply chain partners. All contracts have time limits, but the longer contracted time of a supplier’s service will signal a more trusting relationship in business.

12.2.5. Seek a Demand Pull, Synchronized Supply Chain

In a demand pull system (see Chapter 1), customers place orders before the products are produced or services are delivered. Synchronizing the supply chain with demand pull simply means each supply chain partner is viewed as a customer. When the final downstream customer places an order, it triggers a sequential and systematic chain of customer demand requests back upstream from the final customer all the way through the entire supply chain (Arnseth, 2012d). The key is to manage the demand pull transactions for each supply chain partner in such a way that minimum time and effort are needed to process the demand request, thus reducing wasted time. As lean principles in supply chains are applied in addition to the demand pull synchronized supply chain network, efficiency caused by waste removal is inevitable. Why? Because what is produced and delivered in the supply chain and all the effort to generate the product occurs without waste (for example, overproduction, inventory piling up).

What do many firms that are dependent on forecasts of customer demand do if they cannot wait for customers to place orders ahead of time and pull demand through the production and supply chain systems? One tactic is to segment forecast demand into two categories: certain demand and volatile demand. The certain demand category has to be estimated, but might be only half of the forecast demand that a firm with a high degree of certainty knows will be experienced during a particular time period. The other half can be designated as volatile demand and is considered at risk for the same time period. The certain demand can be produced reliably without wasteful overtime costs or layoffs. Also, the supply chain contracted logistics costs can be bid out in competitive transportation markets, because of the certainty and known demand requirements. This helps reduce supply chain costs on the known demand and permits more to be spent on volatile demand planning efforts. The risk inherent in volatile demand can be outsourced to avoid potentially costly fluctuations (for example, the bullwhip effect).

12.2.6. Seek to Maximize Flow and Eliminate Supply Chain Flow Constraints

Under lean principles, we seek a level and stable production schedule and therefore, a level and stable set of requirements regarding the use of supply chains. This lean supply chain principle suggests stability from stable production scheduling needs to be integrated over the entire supply chain (Nicholas, 2011, p. 393; Kerber and Dreckshage, 2001, pp. 41–51). This principle further advocates that all product flows be in small and frequent amounts, continuously pulled by customers with little variation in production, inventory levels, labor levels, and so on. When variation of any kind is present in any area of the supply chain, it can create congestion, retard flow, and cause wasted time and effort. To maximize flow, we seek an entire supply chain guided by the firm’s level and stable production schedule. Ideally, it will be one that has a fixed number of goods seamlessly scheduled for shipping, production, and distribution that does not require a quick shift up or down over the planning horizon. This means all processes or supply chain activities that contribute variation in production should be investigated for improvement, modification, or even elimination.

Production scheduling variation is not the only limiting factor maximizing product flow through a supply chain. Supply chain flow constraints surface from time to time, which also need to be managed. A supply chain flow constraint might be a supplier that takes too long to deliver goods or a local ordinance or regulation that slows the speed limit to such an extent that it inhibits timely deliveries. Some constraints can be dealt with quickly (for example, replacing a supplier), but other constraints might be impossible to avoid or change (for example, changing laws). Any flow constraints that can be identified should be restructured or eliminated in supply chains where possible. Where it is not possible to eliminate supply chain constraints, other means should be found to compensate and enhance flow. For example, if a speed limit law increases transit time (thus, increasing delivery time), then perhaps new equipment can be used in truck loading and unloading to reduce the time for those tasks (that is, making up for the increased transit time).

The goal of this principle is to maximize flow throughout the entire supply chain (Kerber and Dreckshage, 2011, pp. 67–69). Identifying bottlenecks that create flow congestion, reduce system efficiencies, and reduce performance in the supply chain is essential for eliminating them. Bottlenecks in the production area can be caused by poor equipment that breaks down and delays production, ill-trained employees who cannot complete work on time, or technology that cannot make products fast enough to meet customer demand. Bottlenecks in supply chains can be caused by unaligned capacity in a network, supplier failures of delivery and support, geographic distances that hinder transportation systems, distribution centers whose procedures are outdated or inefficient, or information systems that provide misinformation.

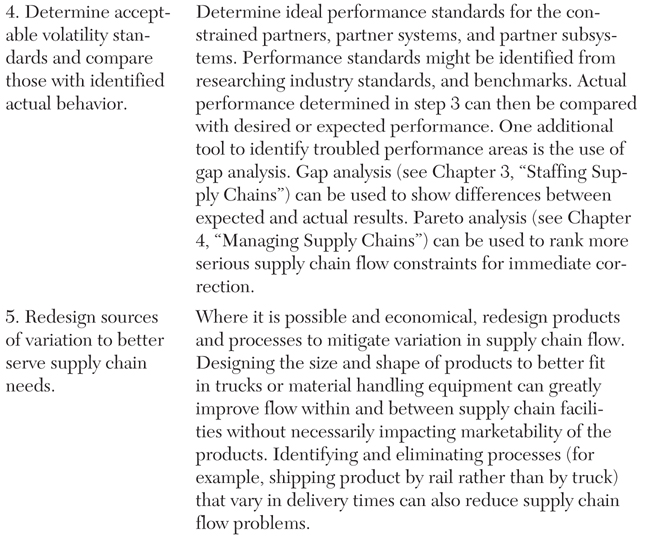

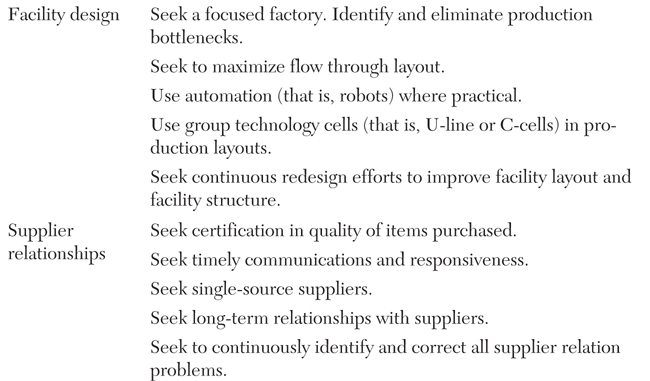

Implementing a lean supply chain management principle of a demand pull system, the synchronization process will often reveal bottlenecks within and between supply chain partners. Bottlenecks in supply chain suppliers can also be caused by supplier service variability (some partners moving faster than others, for example). The slower supply chain partners represent a potential supply chain flow constraint. The imbalance in flow creates congestion, which can in turn lead to bottlenecks. Table 12.2 describes a process to identify supply chain flow constraints.

Table 12.2. Finding Supply Chain Flow Constraints within Lean Philosophy

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2010, pp. 87–89).

Under this principle, lean supply chain information systems are key elements for controlling and enhancing supply chain flow. With highly integrated information systems, supply chain partners can quickly communicate shifts in demand that can avoid costly bullwhip impacts, which add supply chain flow congestion and contribute to other product-flow problems.

12.2.7. Seek Supply Chain Agility

In a customer-focused demand pull environment, lean supply chain operations must be responsive to market changes (Nicholas, 2011, p. 85). They need to be agile (see Chapter 9, “Building an Agile and Flexible Supply Chain”) and able to quickly alter products, processes, and even the supply chain network as changes emerge from customers, both internal and external. While a firm’s production operation can become agile in meeting customer demand changes by lean methods such as mixed-model scheduling (that is, multiple products can be produced without major changeovers in production cells), supply chains, in contrast, permit agility in redesigning network configuration (that is, altering supply chain partners) and flexibility in their capacity to serve customers. One tactic to enhance lean supply chain agility is to redesign and acquire transportation and material handling equipment that possesses a wide range of performance capabilities. Flexibility in equipment capacity permits easy modification to meet shifts in customer demand requirements as needed. In addition, highly flexible information technology may also be critically important to implementing this principle. For example, some radio frequency identification (RFID) tags (see Chapter 2, “Designing Supply Chains”) can be easily reprogrammed to provide additional information as changes in product identification numbers or other product features are altered. Another lean supply chain tactic that can be used to implement this principle is to have highly cross-trained personnel to handle a variety of jobs. These added skills in supply chain staffers allow rotation of personnel from purchasing functions (for example, a purchasing agent moved to a supplier evaluation task). Cross-training can also prevent a breakdown in a supply chain during employee absences (for example, fill in for other supply chain employees absent due to heath or vacation reasons).

According to Amir (2011), the combination of agility and lean supply chain management is a principle referred to as leagile and is a suitable way to exploit both approaches, lean and agile. Basically, it requires selection and setting up of a material flow decoupling point. The positioning of the decoupling point depends on the longest lead time and, at the same time, customer willingness to tolerate a time lag in the decoupling effort. It also depends on the point at which variability in product demand dominates. Downstream from the decoupling point, all products are pulled by customer demand consistent with the lean supply chain management principle. In this way, part of supply chain is market driven, as it should be, by demand. Upstream from the decoupling point, the supply chain is essentially forecast driven. This combined approach enables a level schedule and opens up an opportunity to drive down costs upstream, while simultaneously ensuring that downstream at the decoupling point there is an agile response capability for delivering to an unpredictable demand in the marketplace.

12.2.8. Seek Continuous Improvement

Continuous improvement (CI) must be implemented throughout the entire supply chain and by all supply chain partners (see Chapter 4, “Managing Supply Chains”). For the purchasing firm and its partners, CI may involve advancing visual management in facilities (for example, the use of white boards to post activities where everyone can see them), education, and personnel training to build cross-training skills, education in quality control statistical control methods (for example, to provide continuous monitoring of quality progress), transportation law education, and redesigning physical facilities to improve material handling and product flow. Supply chain partners need to continuously look for ways to add value. Parts suppliers might seek less-expensive, more durable, more aesthetically valued parts for use in supply chains. For example, a supplier component that reduces the weight of a product can create a ripple effect across a supply chain by reducing transportation costs and handling. Teaming supply chain and production personnel might help supply chain managers develop shipping schedules to reduce costs (for example, shipping at low-volume times of the day that might permit a shipping discount). Teaming quality management personnel with supply chain managers can prove beneficial. High quality can benefit the entire supply chain, and low quality can hurt it. High-quality products reduce customer returns. Returns cause wasteful transportation because goods have to be replaced or might even cost the firm valued customers. Inventory managers can be teamed with supply chain managers to help balance small, frequent, lot-sized orders from suppliers to downstream retail customers to minimize costs across the entire supply chain, yet still act to serve the market demand.

12.2.9. Seek Reduced Cost Through Waste Elimination

All the lean supply chain principles previously mentioned can contribute either directly or indirectly to eliminating waste in supply chains. Waste within a supply chain partner’s operations and waste between partners are related to one or all three primary resources of labor, materials, and technology. Lean supply chain management principles seek opportunities for the avoidance of waste within a supply chain partner’s operations. For example, under lean, more frequent shipments to a fewer number of facilities is the norm. A supply chain network to support this type of shipping arrangement can help in negotiating lower-cost contracts with transportation partners. Suppliers also do not have to manage large transportation systems, but focus instead on a fewer number because of the reduction in facilities, which saves time and money. In addition, the same arrangement under lean provides an opportunity to reduce administrative efforts and achieve economies to scale in contracts downstream with distribution and warehousing, because these organizations will be doing business with a fewer number of supply chain partners.

Sourcing supply chain goods is a critical decision in supply chain management. Selecting materials, parts, component supplies, and suppliers can have a substantial impact on the firm’s ability to control waste. Planning decisions on sourcing are usually determined at the strategic level of supply chain planning. Whether to make products or deliver services within the business firm or allow external supply chain partners to handle these tasks can be strategically important in helping avoid waste. For example, suppose a customer demand surge is anticipated in a supply chain that is greater than the supply chain’s capacity to handle it. Third-party logistics (3PL) partners can be contracted for supply chain services in the same way that actual production activities can be contractually outsourced. This tactic can help avoid bullwhip effect wastes that can occur if the firm moves from a stable system to a highly volatile demand situation. Such a strategy helps avoid wasted resources and minimizes rushed and costly decisions that focus on short-term flow problems with potentially wasteful long-term investments in supply chain resources.

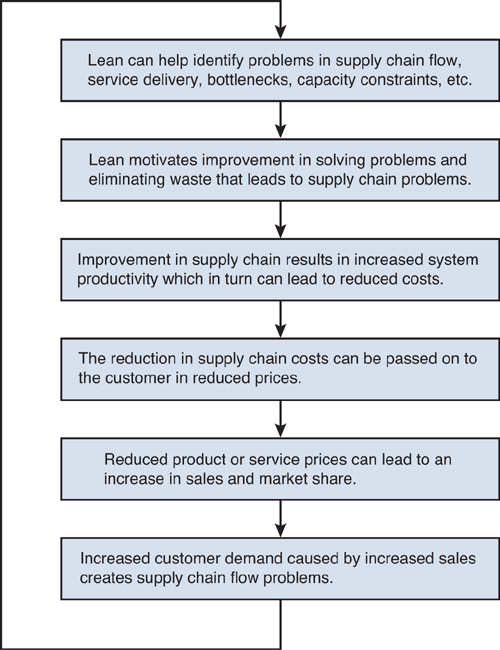

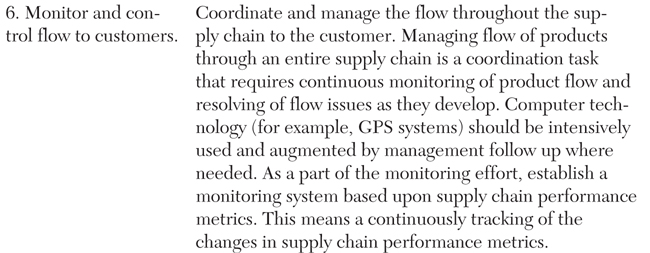

The justification for the application of lean supply chain principles is to improve the value of the supply chain to the organization by reducing waste and becoming more cost efficient, helping the firm increase profitability and market share. The impact of the lean supply chain management strategy is illustrated in lean supply chain productivity cycling process listed in Figure 12.2. Making the lean supply chain management productivity cycling process work well requires reduction of waste. Reducing wasted resources reduces costs, and the cost reduction lowers customer prices, helping make products and services more competitive and consequently increasing market share and profitability.

Figure 12.2. Lean supply chain productivity cycling process

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2010, Figure 2, p. 14).

The lean supply chain principles presented in this section illustrate how the principles are interrelated. Lean supply chain principles are actually intertwined; that is, they relate to one another and require integration, one with the other, to maximize potential benefits.

12.3. Other Cost-Reduction Strategies

Lean-based strategies are invasive and can completely encompass a firm’s cost-reduction strategy. Other strategies are more focused on limited domains (for example, procurement) within organizations. Cost strategies available to reduce or control costs for organizations are as numerous as there are costs to be controlled. Some listed here afford users opportunities that, when combined with lean supply chain management principles or other cost strategies, can create a comprehensive cost management program.

12.3.1. Procurement Partner Competition

In most supply chains, procurement represents the largest long-term cost item. To help ensure the best price for supplies, a firm should seek a pure competition environment that is highly competitive with large numbers of suppliers helping to create market pressure that will force prices down, helping to contain costs. In some situations, the purchasing firm should adopt a strategy to help build those competitive markets. A proactive role in fostering competition on bidding prices by suppliers is a part of this strategy. A tactic for this strategy is a reverse auction. A reverse auction is a process where a supplier offers a fixed duration bid in a purchasing event hosted by a purchasing firm (Blanchard, 2007, p. 82). While potential bidding suppliers have to be prequalified to meet the purchasing firms other needs, the purchasing organization’s hosted event collects and shares bid prices with other suppliers offering bids. The reverse auction is usually accomplished over the Internet (giving rise to the terms e-auction or e-sourcing). Suppliers are then allowed to revise bids during the fixed time period of the auction in hopes of getting the contract. Bidding helps to reduce the prices charged, which reduces the cost to the client firm.

12.3.2. Standardization and Commoditization

Under the standardization and commoditization strategy, and wherever possible, products and services should be transformed into standardized products that use standardized components (“Global Manufacturing...,” 2011). Standardization reduces customization of products and components, thus reducing the need for larger inventories and associated costs. In addition, as products and components end their life cycles and become obsolete, fewer inventory items are needed, and that means fewer will become obsolete. In fact, the component parts may actually have their life cycles extended (for example, a standardized screw that can be used in hundreds of products will last as long as the oldest product in the set of hundreds).

Standardization of services reduces the number of service skills and tasks needed to perform jobs. That can help reduce service costs and training. In addition, standardized services provide opportunities to use the same sets of service related supplies (a form a standardizations of supplies), reducing those costs.

The downside of this strategy is that it can increase competition. Transforming a product or service into a commodity (that is, an undifferentiated product or service) means other competitors can offer a similar product or service. Some balancing of customization with the standardization of the product is called for in using this strategy.

12.3.3. Combined Organization and Opportunity Analyses for a Cost Strategy

This cost strategy is similar to the basic organizational strategic planning process (see Chapter 1). It has two parts represented by two types of analyses: (1) an organization analysis and (2) an opportunity analysis (Carter and Choi, 2008, pp. 60–62). The organization analysis looks internally at the supply chain organization, seeking to determine how the supply chain functions can be streamlined and reorganized to cut costs and improve effectiveness and productivity. A reorganization and realignment of supply chain functions takes place to reduce costs in the short term. This is followed by the opportunity analysis, which looks externally to determine any best-in-class practices in various industries of cost management practices that can be applied to the firm’s supply chain department.

12.3.4. Centralized Buying

Under a centralized buying strategy, an organization-wide buying agreement can be used for cost management purposes, whereby one department or specific supply chain professional is given total authority and responsibility of purchasing for an entire organization (Carter and Choi, 2008, p. 64). Consolidating purchases for entire departments or divisions gives the person in control greater clout to obtain a better purchasing price and therefore can reduce organizational costs. This strategy also reduces administrative costs by reducing the need for multiple decision makers and purchasing personnel. One tactic useful in the implementation of this strategy is pool buying (that is, the consolidation of purchasing requirements from multiple departments or divisions of a purchasing firm into a single order). This helps lower the price because of the volume of business with the suppliers is attractive, so it is worth lowering prices to obtain the contract. It helps reduce the supplier’s costs, because the firm can run larger production runs and experience economies-to-scale cost reductions.

The downside is that there are fewer decision makers to glean information from the purchasing firm’s internal customers. Also, it can slow the procurement process down if there are not sufficient numbers of procurement staffers to process requests from distant divisions in the firm.

12.3.5. Outsourcing

Outsourcing (see Chapter 13, “Strategic Planning in Outsourcing”) supply chain activities to reduce costs is a common strategy in a cost management program (Schniederjans et al., 2005, pp. 10–11). The act of engaging suppliers to provide goods to a purchasing organization is an act of outsourcing production and procurement tasks needed to produce and deliver the supplier’s goods. The cost advantages of outsourcing are rooted in the use of others to do the work for the client firm. This strategy reduces costs when used by a client firm to perform a supply chain task where an outsourcer can provide a service cheaper than the client firm. Supply chain firms all have core competencies (see Chapter 1) allowing them to perform some activities better than other firms. They also have noncore activities that outside firms excel in (and perhaps with less expense to the client firm). Those noncore activities are the candidates for outsourcing. If a price can be negotiated for less expense, costs can be reduced by outsourcing those tasks.

12.4. Other Topics in Lean and Other Cost-Reduction Strategies in Supply Chain Management

12.4.1. Transforming Lean Procurement Principles in Service Organizations

Organizations have transformed lean management principles from manufacturing to service organizations in supply chain functions like procurement. Arnseth (2012d) found such a transformation for a global procurement organization, Capital One Financial Corporation. Utilizing the following lean principles, Capital One was able to transform administrative and service activities connected to their financial transactions into a lean supply chain management environment. Lean procurement changes reported include the use of the following principles:

• Use of operational visibility: Use of massive white boards (that is, marking boards on which notes and other messages were written) allowed them to keep track of the steps involved in complex procurement projects. The white boards allow management to keep up-to-date on progress (and lack thereof) and to identify problems to reposition efforts quickly in order to correct and improve service flow on slow progress projects.

• Use of work segmentation: Segmentation of tasks required for procurement projects so each task could be tracked to help identify and avoid wasted time updating personnel on the current status of progress, as well as helping to locate wasted efforts and remove them. The firm identified processes that needed to be changed to avoid disruptive and wasted efforts. For example, some internal customers brought in disorganized and incomplete procurement contact information that would delay the procurement process. Internal customers were encouraged to improve the completeness of their procurement documentation or would face delays in processing.

• Use of cross-functional teams: Applying Pareto analysis, the firm employed teams to figure out ways to fast-track low-complexity projects, improving flow. Learning what worked best, the same principles were eventually applied to high-complexity projects.

• Empowering employees: Building transparency in job opportunities, the firm allowed employees to select the types of job assignments they believed would be of most interest, rather than having the firm select and assign staff to jobs, which increased motivation and improved efficiency for the firm.

• Use of education to transform the organization: Creating a program called key initiative (KI), forums were initiated that allowed team members to quickly share information on lean implementation tactics and new ideas that emerged over time. Staffers were able to think “out loud” and learn in public.

• Use of continuous improvement: As a part of the KI, weekly meetings were also used to integrate members from other departments to see the status of projects and share ideas for continual improvement.

The reported impact resulted in eventual acceptance of lean supply chain management principles. The benefits included a faster flow of procurement documents in less time and greater consistency in delivery and contract outputs. Contracting cycle time was reported to have dropped by 80%. In addition, the lean principles were, after some anxiety, quickly accepted, altering the culture in procurement practices in record time.

12.4.2. Mistakes in Lean Implementation

Supply chain activities are often highly connected to successful use of equipment (for example, trucks, material handling, technology). Unless the equipment is well maintained, it may result in costly repairs, product failures, and unsafe conditions. Poor maintenance results in costly waste that runs counter to lean supply chain management principles. Fitzgerald (2011) has suggested several practices in the implementation of lean supply chain management programs that should be avoided as they relate to equipment maintenance, including the following

• Inadequate measurement of lean maintenance implementation: Failure to measure the maintenance function before and after a lean maintenance program has been implemented should be avoided. Using a computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) (that is, computer software that can compile maintenance records, review work orders, track spare-parts inventory) can help supply chain managers make informed decisions about buying versus repairing and utilizing preventative maintenance. It is important to invest time to create work processes and train supply chain personnel in order for the CMMS to correctly report operational performance metrics needed to monitor maintenance performance and avoid wasted effort.

• Lack of lean educators: Most lean supply chain management programs are lacking instruction, which leads to less than desirable outcomes. The implementation of lean needs to become a culture within a supply chain organization and the greater organization as a whole. To accomplish cultural change requires the use of corporation coaches and mentors backed by upper-level management.

• Failure by overreaching on an implementation project: Selecting an initial project that is too big or too complex dooms the program and future initiatives to failure, discouraging future use and damaging the motivation needed to implement the project quickly and successfully. Selecting a smaller and less-complex initial lean supply chain project will likely result in immediate success and provide momentum for future lean initiatives. The firm should plan to obtain a series of initial successes whereby lean projects help to quickly move an organization’s cultural acceptance of the principles.

• Failure to build organizational support and promote the idea of lean supply chain management: Without constant reminders by upper management and maintenance managers of what lean supply chain management means, how it is implemented, and what value it contributes to the organization, staffers may not feel it is worth the effort to implement. Consistency and reinforcement of the lean directive from top management down through supervisors to operators and maintenance personnel must be visible to all. As employees start to associate the implementation of lean with the successes it brings, the culture will change to better support lean principles.

• Avoid shortfalls of needed resources: To make lean happen requires education, training, skill development, and time. It necessitates resources. In addition, to aid in making lean happen requires a willingness to listen to employee lean suggestions and, where possible, to implement them, even if it involves some risk to operations. The real potential of lean supply chain management principles will always be realized through the employees who implement them. They are closest to the implementation, so who better to know what might work?

12.4.3. Collaboration as a Cost-Reduction Strategy

Competitors tend to own the same technology and equipment use the same processes and understand the same business needs and wants as any firm in a particular industry or marketplace. Sometimes, a firm may have excess capacity that it would like to transform into an alternative source of funds, whereas others might need the extra capacity. Indeed, in many industries, as one firm increases sales, another competitive firm might have a decrease. Sharing warehousing, distribution, and manufacturing resources may be a cost strategy that can provide unique and beneficial improvements for both firms. According to Siegfried (2012), competitors collaborating to share resources can be a useful cost-reduction strategy. Referred to as a horizontal collaboration, working with a peer competitor to share resources must be in accordance with U.S. antitrust laws. Siegfried (2012) suggests that to enter into a horizontal collaboration for mutual cost-reduction benefit will require several prerequisites considerations:

• A trusting relationship: A solid working relationship that will build trust based on openness is needed. An initial outsourcing arrangement between two competitors might be a useful tactic. This would include sharing financial information relative to the alliance as well.

• Identify areas where performance can be enhanced: While collaboration is exploratory, there may be known areas where competitors excel and can bring resources to the table as an enticement for horizontal collaboration. The supply chain area of joint collaboration can and should be comprehensive, including procurement, manufacturing, and distribution.

• Establish joint planning committees: Both companies need to enhance transparency and cooperative planning by have meetings of a joint steering committee to regularly examine and address process improvements, service levels, inventory issues, and other operational areas of concern related to the alliance. The committee should include vice president-level members and executives from manufacturing, finance, logistics and planning. The meetings should be held face to face (to build trust) at corporate headquarters, at least on a quarterly schedule.

• Establish a willingness to work together attitude: Problems may develop with this type of alliance, and both parties must be mentally conditioned to work together, regardless of how challenging the problems that surface may become.

The results of this cost-reduction strategy reported by Siegfried (2012) include significant cost savings in fixed costs and capital investments, exceeding the firms’ expectations. Other benefits include the opportunity to afford resources that the firms individually could not invest in, but benefit by sharing.

12.5. What’s Next?

Cost volatility trends appear to be the major concern now and into the future. Cost management is predicted to be at the top of the list of concerns for supply chain managers. Several studies suggest cost management is now more than ever a critical success factor for supply chains going forward. According to a survey by the Aberdeen Group (“Globalization and...,” 2011), cost management concerns were the top two pressures for global supply chain managers looking forward in 2011. According to IDC Manufacturing Insights (“Reducing Overall...,” 2012) a survey of 350 supply chain managers found 80% of the respondents thought reducing overall supply chain costs was the number one supply chain priority for 2013. Miller (2012), looking at critical success factors for the year 2012, echoed the cost management concern theme, suggesting that efforts to reduce costs are what is needed. One tactic that can be used to deal with increasing cost trends is to use purchasing contracts. The present volatility in prices (costs) and their trend upward could be reduced in the short term by offering a longer-term purchasing contract that takes into consideration future reduced prices (similar to long-term loan rates offered by banks in fund construction of homes and buildings). Another tactic to support a cost management program is suggested by the World Economic Forum (“Outlook on...,” 2012). They propose unpacking the sources of potential supply chain costs into different components, to separate policy drivers from other factors (for example, infrastructure weaknesses) as a means to focus corrective cost-reduction efforts more efficiently and to eliminate waste.