4. Managing Supply Chains

4.2 Managerial Topics in Planning/Organizing Supply Chains

4.2.1 Leading with an Entrepreneurial Spirit

4.2.3 Developing a Procurement Plan

4.3 Managerial Topics in Staffing Supply Chains

4.4 Managerial Topics in Leading/Directing Supply Chains

4.4.1 Leadership Styles and Obstacles

4.4.2 Leading Evolutionary Change in Supply Chain Departments

4.5 Managerial Topics in Monitoring/Controlling Supply Chains

4.5.1 Setting Up an Internal Monitoring and Control System

4.5.2 Monitoring External Demand with Market Intelligence

Terms

Cause-and-effect diagrams or fishbone diagram

Committee of sponsoring organizations (COSO)

Continuous improvement (CI)

Failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA)

Groupthink

Opportunity flow chart

Pareto charts

Should-cost modeling

Social loafing

4.1. Prerequisite Material

In a general sense, managing a supply chain is an act of working and bringing people together to accomplish a desired set of supply chain goals and objectives using available resources efficiently and effectively. The basic functions of supply chain management involve the same functions all managers perform, which includes planning/organizing (that is, deciding what needs to be done to accomplish goals and generating plans to enact them), staffing (that is, recruitment and hiring personnel for jobs), leading/directing (that is, motivating and guiding people to do their jobs), and monitoring/controlling (that is, checking progress against plans and ensuring compliance) to achieve a common purpose (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Management). To carry out these basic functions, managers are expected to perform a variety of roles, including interpersonal coordination and interaction with subordinates, peers, and superiors to communicate, motivate, mentor, and delegate work activities. Besides decision making, managers are also expected to provide an informational role of sharing and analyzing information.

The three management functions of planning/organizing, staffing, and leading/directing were introduced in the presentation on organizational design and strategic planning in Chapter 1, “Developing Supply Chain Strategies,” and Chapter 2, “Designing Supply Chains.” The staffing function was topically introduced in Chapter 3, “Staffing Supply Chains.” The focus of this chapter is to build on these foundations with additional topics.

4.2. Managerial Topics in Planning/Organizing Supply Chains

Some managers wait until a problem occurs to manage it. Better managers develop contingency plans just in case a problem comes up. Great managers establish a contingency roadmap for problem resolution that builds from the organization’s mission statement through policy development and everyday events. Because of the diversity of problems and management issues that surface in any supply chain, only a cursory treatment of select planning topics can be presented here. The topics discussed include leading with an entrepreneurial spirit, managing complexity, and developing a procurement plan. Other related topics are presented in subsequent chapters.

4.2.1. Leading with an Entrepreneurial Spirit

In any stage of a product life cycle, but more so for the Introduction Stage, leaders should encourage employees to think like entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs start up companies in the Introduction Stage of the product life cycle. They have to be adaptive, creative, innovative, and enthusiastic. Such spirit will unlock avenues of productivity and motivate employees to make substantial contributions.

To encourage supply chain personnel to think like entrepreneurs, Anderson (2011) suggests three managerial tactics: encourage experimentation, encourage what-if thinking, and appreciate the value of influencers. Experimentation can be encouraged by undertaking small projects that experiment with new ideas. What-if thinking can be encouraged by running though scenario problem solving exercises such as disaster planning, rapid customer growth modeling, or geopolitical disturbances. A manager needs to be able to influence employees and subordinates. While some managers rely on positional power, those who can genuinely influence others have real power to motivate and cause an organization to advance toward goals. A tactic to make everyone an influencer is for the manager to project a positive attitude. Other tactics might include proposing a continual set of new ideas to solve problems or to reexamine and modify ways for staff to do their jobs.

In summary, the key to an entrepreneurial spirit is for managers to encourage communication and change ideas. They should encourage development of new ideas as if the employees were starting up a new business operation. By doing so, new contributions and innovations will be an inevitable outcome.

4.2.2. Managing Complexity

Every component within the supply chain can add complexity and problems for management. There are many types of complexity in supply chains. Examples of a source complexity can include product complexity caused by an overly complex product design. Such a design might lead to an increased size of a supply chain globally to support the product. The processes used to produce a product can be highly complex, requiring substantial assembly work, thus adding distribution complexity of planning efforts to link the global assembly facilities. Network complexity can be created when the number of hubs in a network increases, requiring more effort to communicate and control it. Customer complexity can occur as customers demand more service options or when the customer base expands downstream or upstream as the supplier base increases to meet increased customer demand. The need for greater interaction with more numerous suppliers adds complexity in planning roles.

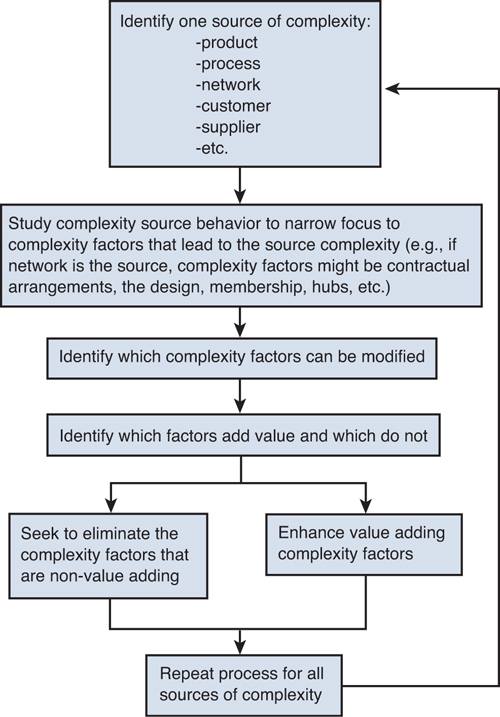

Regardless of the source of complexity, it needs to be planned for and managed. One conceptual modeling approach to aid in planning the management of sources of supply chain complexity is presented in Figure 4.1. The conceptual model in Figure 4.1 suggests that a source of complexity in a supply chain (and there are many) should first be identified and then studied to identify complexity factors or factor complexity. A customer may be a complexity source, but it is complexity factors such as the way the customer communicates with the firm to place orders or return merchandise that may be the complexity factor causing the problem. To aid in this planning task, several quality management methodologies can be used to break down complexity sources into complexity factors (see Table 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Conceptual model for managing complexity

Table 4.1. Quality Management Methodology Useful in Complexity Management

Source: Adapted from Table 7 in Schniederjans (2010), pp. 21–22.

After the complexity factors have been identified, a determination of those that can be modified as opposed to those that cannot must be made. Assuming contractual and other constraints permit some modification, the next step in the conceptual model requires identification of those complexity factors that are value-added from those that are not. It should be understood that some complexity is actually a good thing. Customers may value a complex set of product offerings, making the diversity of those products within a distribution system a complexity challenge. The complexity factors that contribute value should be encouraged (or at least allowed), while those that are non-value-adding should be minimized or eliminated. Finally, the process of managing complexity as presented in Figure 4.1 needs to be repeated for each possible source of complexity. This repeating process, like the quality management methods in Table 4.1, needs to be viewed in the context of continuous improvement (CI) (that is, a never-ending sequence of quality activities ideally leading to perfection). Indeed, in the case of supply chain management, the need for repetition of the complexity modeling process is particularly urgent and critical because of the nature of dynamic changes undertaken in supply chains.

4.2.3. Developing a Procurement Plan

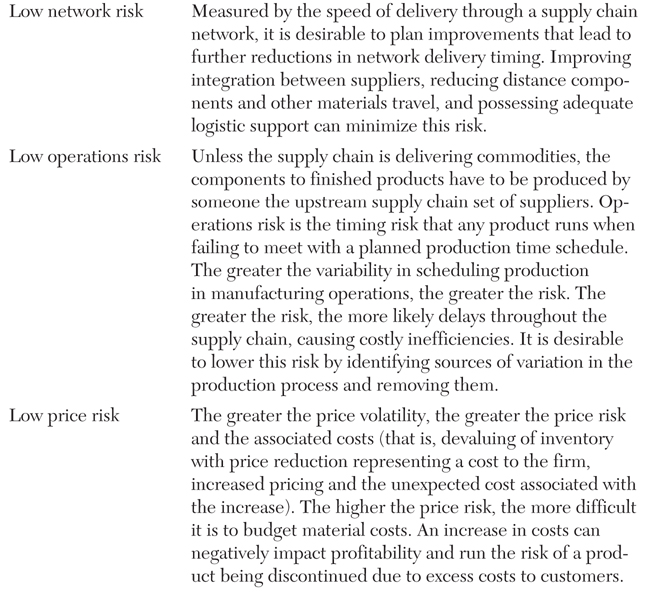

There are many dimensions to planning an organization’s procurement operations. The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) (www.ism.ws/) suggests a formal statement be used: procurement management plan (that is, defines how supply management will oversee the procurement process). This plan covers such issues as contracts to be used, personnel assignments and responsibilities, documents, coordination activities for supply chain partners, and internal production/reporting requirements. The plan also designates the management of lead times and risk, processes to identify qualified suppliers, and performance metrics that will be used for monitoring and control. To develop the procurement management plan requires an understanding of critical success factors (CSFs) in establishing such a plan. Table 4.2 describes commonly considered procurement CSFs.

Table 4.2. Procurement Plan Critical Success Factors

Table 4.2 also illustrates a variety of risk taking required in planning procurement. Among other things, managing a procurement department involves managing risks. Many possible tactics can be implemented to manage procurement risk. One tactic to reduce risks with uncertain demand is through options contracts. An options contract is one where a buyer prepays a small faction of the product price in return for a commitment from the supplier to reserve the use of the supplier capacity up to a defined level. Like a reservation (it is actually referred to as a reservation price or premium) for a future order of goods from a supplier, the buyer has the option of purchasing goods up to the capacity limit for a given period of time. If the buyer chooses not to exercise the option, the reservation price payment is lost. Some options contracts can set a fixed price for the future purchase of items or allow the supplier to set a flexible price, where the supplier can charge an additional amount or price per unit (referred to as the exercise price) once the buyer exercises an option to purchase items. Although this approach removes some sourcing risk from the buyer, it can increase price risk if suppliers are given the flexibility to set any exercise pricing they desire.

Another risk minimizing tactic is though the use of portfolio contracts. In a portfolio contract, a buyer enters into multiple contracts with different suppliers. They have different prices and levels of flexibility, which allow the buyer to hedge against inventory shortages from any one supplier. By having a mixture of suppliers that offer low-price/no-flexibility/fixed-quantity contracts, average-price-with some-option-flexibility contracts, and spot market purchasing (that is, open market with no contractual arrangements for price or quantity), a buyer can hedge against shortages and price increases.

Although it might seem consistent with Japanese methods of supplier relations to establish long-term contracts, these tend to invite all the risks and difficulties presented in Table 4.2. Binding a firm to a long-term commitment is risky. It could lead to greater uncertainty for financial risk by wasting money on inventory that might not be needed because of declines in customer demand, network risks in shipping goods not demanded, operations risks in producing goods not demanded, greater price risks because of inevitable pricing changes over a longer period of time, higher innovation risks of obsolescence for inventory no longer demanded, and greater supplier risks in situations where long-term low prices during inflationary periods creates unfairly low prices that weaken and hurt the profitability of suppliers. However, if flexibility can be built in to a long-term supplier relationship, the mutual supply chain partners working together to help one another can eliminate many of the risk factors. Chapter 11, “Risk Management,” discusses this collaboration.

4.3. Managerial Topics in Staffing Supply Chains

Chapter 3 introduced the topic of staffing, and now this section builds on that foundation by covering topics such as building teams and mentoring programs.

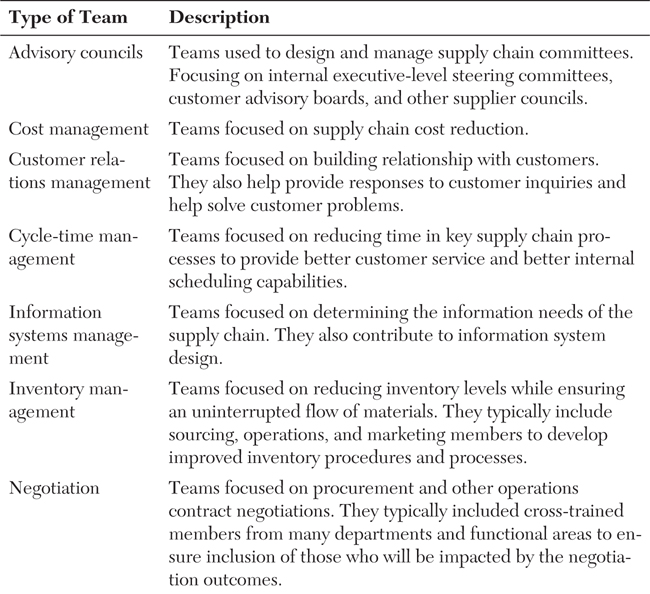

4.3.1. Building Teams

Many teams serve the planning and managing needs in supply chain management departments (see Table 4.3). However, team effort does not always lead to success. Teams that are poorly run have resulted in negative outcomes, such as increased costs, stress, and lower group cohesion (Lussier and Achua, 2004, pp. 263–265). In general, effective teams can be described in the context of four characteristics presented in Table 4.4 (Dunphy and Bryant, 1996; Cohen and Bailey, 1997).

Table 4.3. Types of Supply Chain Teams

Source: Adapted from Table 14.3 in Fawcett et al. (2005), p. 445; Carter and Choi (2008), p. 166.

Table 4.4. Characteristics of Effective Teams

Source: Adapted from Table 5 in Schniederjans et al. (2010), p. 112.

How can teams become more effective? It starts with staffing the right leadership and participants and defining their roles. Leadership can guide teams and help them evolve toward achieving their objectives. Lussier and Achua (2004, p. 267) have suggested guidelines that can be used to aid teams to become more effective:

• Seek to develop trust and norm expectations.

• Seek to identify team strengths and build on them.

• Seek to place emphasis on team recognition and team rewards.

• Seek to recognize individual needs and try to satisfy them in a timely manner.

• Seek to recognize team needs and try to satisfy them in a timely manner.

• Seek to support team decisions.

• Seek to empower teams to accomplish their work.

• Seek to provide teams with work that will motivate and challenge them.

• Seek to develop team capabilities and flexibilities to deal with change.

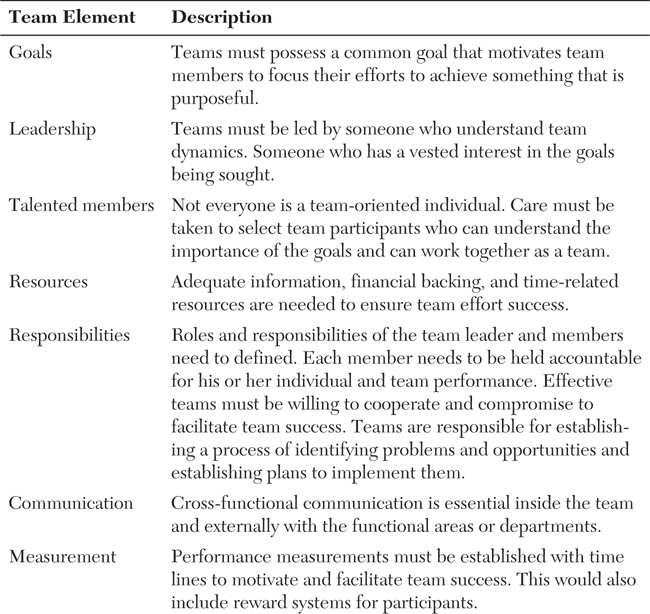

To staff and build a team requires a basic understanding of the elements used in their creation. Table 4.5 lists a number of basic team-building elements. Team building also requires a balancing of advantages that teams bring to a firm with the disadvantages (see Table 4.6).

Table 4.5. Team-Building Elements

Table 4.6. Advantages and Disadvantages of Teams

Source: Adapted from Table 14.5 in Fawcett et al. (2005), p. 447; Flynn (2008), pp. 101–103.

Some firms have extended their use of teams by allowing them greater autonomy through self-management. In self-managed teams (SMTs), the role of the leader is to facilitate processes and support team members, rather than focusing on traditional command and control functions. In SMTs, leaders set the general direction and goals, and team members make decisions on their own (and develop implementation plans). Characteristics of SMTs include the following:

• Having the authority to manage their work, set goals, plan, staff, schedule, monitor quality and implement decisions

• Members having a broad base of experience to avoid outside management but when needed expert support is included

• Coordination and cooperation to be independent of other teams and to handle their own coordination efforts

• Internal and flexible leadership where members often rotate as leaders within the team

The benefits of SMTs reported in the literature include the following:

• Employees are involved in controlling tasks whereby they are free to make original contributions and advancements.

• The leader has time for new or other planning activities.

• Employees have opportunities to learn and develop.

• Employee motivation and job satisfaction are increased.

4.3.2. Mentoring Programs

Today’s lower-level manager may become a mid-level manager or even an upper-level supply chain executive. One of the best strategies to ensure adequately trained and experienced personnel exist to staff mid-level and upper-level management positions is to use a mentoring program. A mentoring program involves upper-level managers mentoring subordinates. Mentoring is a process for informal education or knowledge exposure as well as for providing psychosocial support to the recipient (that is, protégé) on topics relevant to work, career, or professional development. Mentoring involves informal communication transmitted by phone, Internet, video conferencing, or other technologies, as well as face-to-face communications over a sustained period of time, between a person who has greater knowledge or experience (the mentor) and a person who may have less (the protégé).

Roach (2011) believes that mentors act as guides to help protégés navigate workplace challenges. They provide insight to ensure mistakes are not repeated and common pitfalls are avoided. Mentors can provide opportunities for protégés to discuss ideas in a safe and trusted environment. Roach suggests that successful mentoring programs can be characterized by the following organizational factors:

• Programs should be open to all employees.

• Expectations of mentoring relationships should be understood by all participants.

• Mentor training or knowledge is needed for mentors.

• Flexibility in mentor assignments is needed.

• Confidentiality and integrity of participant interactions are maintained.

• Measurable targets are set and monitored frequently.

• Technologies are used to ensure consistency, timeliness, and frequency of interactions.

Mentoring programs not only help to provide adequately trained staff are available when needed but also increase retention rates, lessening the need for staffing in the first place (Roach, 2011).

4.4. Managerial Topics in Leading/Directing Supply Chains

Providing leadership and directing the activities of a supply chain permits managers to set a course and guide employees along that course. The topics discussed in this section include leadership styles and obstacles and leading evolutionary change in supply chain departments.

4.4.1. Leadership Styles and Obstacles

Leadership is an integral part of the group phenomenon. There can be no leadership without followers in a group. Leadership is an influencing mechanism for guiding members of a group with a course of action to achieve specific goals. Leadership involves initiating a social structure (that is, a formal hierarchy with a leader on top). Some managers utilize a style of leadership to express their approach to leading an organization. There is considerable research on leadership styles (that is, a collection of leadership models and approaches used to implement leadership in an organization), and Table 4.7 describes some of the most common types. These styles can be used (and have often been used) as a model for implementing leadership in an organization.

Source: Adapted from House and Podsakoff (1994, pp. 58–64).

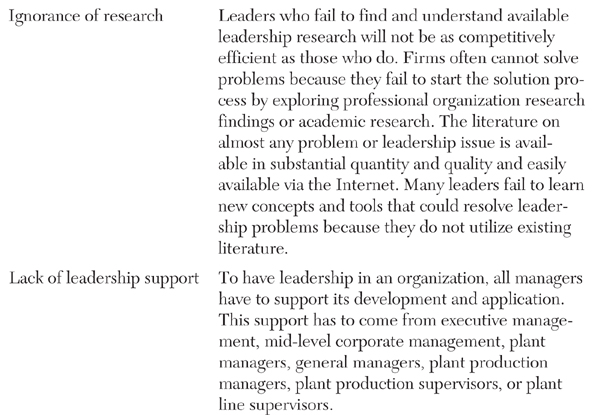

Implementing a style of leadership is not without difficulties. There are always obstacles that prevent supply chain managers from managing areas of responsibility. In addition to the external reasons (for example, organizational resource constraints), some obstacles to leadership are self-inflicted by leaders themselves. Table 4.8 describes a number of these self-inflicted obstacles to leadership. They should be viewed as behaviors that can and should be avoided.

Table 4.8. Obstacles to Leadership

Source: Adapted from Table 6 in Schniederjans et al. (2010), pp. 114–115.

4.4.2. Leading Evolutionary Change in Supply Chain Departments

The stable environments that supply chains historically operated in did not demand the rapid adaptation required today. The supply chain leaders who actively pursue organizational strategies that encourage developments needed to make overnight changes in supply chains will position their firms to evolve or reorganize based on up-to-the-minute world-market changes.

Supply chains and their departments need to change and evolve to meet the rapid demand shifts. Evolutionary leadership is the means to implement that change. Arnseth (2011a) suggests successful evolutionary leadership will include an orientation toward innovation, performance outcomes, a customer focus, and diplomacy. Innovation orientation refers to a constant reexamination of corporate activities as they relate to a firm’s business model, both inside and outside. Suppliers will increasingly be asked to find applications of innovation in the performance of their missions. Performance outcomes orientation refers to a movement toward overall outcomes, rather than traditional contract cost outcomes. Supply management should look at the value side of things (for example, suppliers who work with a manufacturer to produce new cost-saving solutions through alternative materials or better quality) rather than just costs. The customer-focus orientation refers to moving supply chains into more customized networks to serve individual customers. For customers like Wal-Mart that primarily focus on a customer cost-reduction policy, the supply chain should be customized to focus primarily on just a cost-reduction objective. The diplomacy orientation refers to use of tact in negotiations to gain advantage or to find a mutually acceptable solution to a common problem or issue. Long-term suppliers may be needed for organizations. Being nonconfrontational and polite in negotiations is one way of being diplomatic. Although transactional partners who are meant to be short-term supply chain partners might not need the same treatment, in the longer term a firm might not know which firms will end up being long-term suppliers. It is a better policy to be diplomatic with all suppliers.

4.5. Managerial Topics in Monitoring/Controlling Supply Chains

It is not enough to set and lead an organization’s supply chain objectives. Managers must know the progress they are making toward those objectives and when corrective control is needed. The topics discussed in this section include setting up internal monitoring and control systems and monitoring external demand with market intelligence.

4.5.1. Setting Up an Internal Monitoring and Control System

The management function of monitoring usually refers to establishing appropriate supply chain metrics to track system performance for reporting to management. The management function of controlling refers to maintaining supply chain compliance based on designated metrics, which can be used to identify where a supply chain needs to be brought into compliance. Key to both functions are supply chain metrics.

Supply chain metrics literature is substantial and is organizationally specific in application. Supply chain metrics can be grouped by type of performance in various aspects and locations within a supply chain network. Some of the more typical performance areas include monitoring for control purposes of assets, cost, customer service, productivity, and quality. Table 4.9 describes some specific supply chain performance metrics.

Table 4.9. Supply Chain Performance Metrics

Source: Adapted from Table 16.1 in Bowersox et al. (2007), p. 378.

To use metrics, monitoring and control systems need to be established. Unique to the supply chain they serve, these systems need to be customized to help each organization achieve its objectives. To help organizations plan monitoring and control systems, professional consultants are commonly utilized. Professional organizations are also devoted to developing monitoring and control systems. For example, the committee of sponsoring organizations (COSO) provides several comprehensive frameworks on guidance in enterprise risk management and internal control and fraud deterrence. The goal of this organization is to improve all organizational performance and governance while reducing the extent of fraud in organizations (www.coso.org/aboutus.htm).

Based on their frameworks, COSO suggests that effective and efficient monitoring is best achieved by

• Establishing a foundation for monitoring, including support for and by upper management, adjustments to organizational structure, and a baseline understanding of internal control effectiveness

• Designing and executing monitoring procedures that seek to evaluate control information used to address risks to organizational objectives

• Assessing results and reporting them to appropriate parties

COSO developed the framework in response to executive needs for effective ways to better control their firms and help ensure that organizational objectives related to operations, reporting, and compliance are achieved. This framework has become widely used as an internal control framework in the United States and has been adapted or adopted by numerous firms in countries around the world. COSO framework implies that five components are needed to establish an effective monitoring and control system applicable to supply chain management, as follows:

• Establishing a control environment foundation that guides the discipline and structure of the system

• Risk assessment, involving the identification and analysis of relevant risks to achieving predetermined objectives

• Monitoring control activities, including policies, procedures, and practices related to achieving objectives and any risk-mitigation strategies that are carried out

• Monitoring information and communication support for all control components at the individual employee level to ensure they can carry out their respective duties

• Monitoring external oversight of internal organization controls by management or by designated parties outside the process

Some have questioned the usefulness of the COSO system (Shaw, 2006) in light of recent U.S. government legislation, but few can deny the framework is an ideal place to begin the process of developing monitoring and control systems.

4.5.2. Monitoring External Demand with Market Intelligence

Monitoring the external supply chain partners upstream and downstream sometimes requires a more complex approach than just using metrics. This holds particularly true when examining future customer demand and how it may impact the entire supply chain. Yet monitoring customer demand is essential to avoid waste and inefficiency in a supply chain.

In the Introduction Stage of a product life cycle (refer to Chapter 1) when demand gradually begins to increase, there are always risky situations where demand could drop off completely because a product turns out to be a market failure. Alternatively, demand could shift into the Growth Stage of the product life cycle. To manage either of these situations in the most efficient and effective manner requires market intelligence (Mullan, 2011). Market intelligence (MI) involves gathering and analyzing information about a firm’s markets to determine opportunities and plan further strategies to deal with customer demand. Although MI is not a new approach in business, it has not been fully appreciated or fully utilized in the supply chain management field. Table 4.10 describes some of the areas where MI can be applied to support supply chain decision making and assessment.

Table 4.10. Supply Chain Market Information Analysis Applications

Source: Adapted from Mullan (2011), p. 24.

Mullan (2011) suggests there are four areas where MI can be used to gain information applicable to managing a supply chain: supply market analysis, category/commodity intelligence, supplier health/performance, and financial risk management. In addition to proving product consumption and price-forecast planning information, the market analysis helps managers identify capacity changes that impact pricing and product availability to customers and trends in raw materials and currencies that could be useful for planning current and future supply chain scenarios.

The product category/commodity MI information helps identify category cost drivers, commodity should-cost models, and market inflation and deflation trends, all of which help operations decision making for product planning. One particularly important feature of this is the capacity of MI in helping identify the product life cycle, which in turn aids overall product and supply chain network planning.

Another informational dimension of MI in managing upstream suppliers is its ability to assess the financial stability and overall health of suppliers. MI helps identify how well suppliers have the capacity to deal with demand shocks and adapt to downstream supplier and manufacturing needs for growth or expansion. In this regard, it helps in managing risk that a manufacturer faces in dealing with upstream suppliers.

4.6. What’s Next?

Control of supply chain operations has been tightening for the past couple of years because of the recessions in many countries. It appears that the trend is for further tightening for the foreseeable future (“Globalization and...”, 2011). Factors such as the desire to cut costs have driven many firms to use tactics and strategies like outsourcing to achieve lower product costs. Supply chain departments have responded to such strategies by building longer and more diverse supply chain networks. As a result, the issue of controlling these supply chains has offered great challenges to managers. These challenges have not gone unnoticed in the literature. The Aberdeen Group (“Globalization and...”, 2011) found in their survey of supply chain managers that most view the level of control and coordination with external supply chain partners has become a strategic critical success factor looking forward through the year 2015. To deal with the control issue, it is recommended that firms channel their customers’ and other stakeholders’ desire for visibility into a dual role. One role would be to provide information for the stakeholders and managers to use for monitoring and controlling their supply chains and other operations. Advances in mobile and other communication technologies permit monitoring of the flow of goods and services as far upstream as the first-, second-, and even third-tier suppliers through the operations transformation process to the customers. For example, customer order tracking systems, similar to those used by the U.S. Post Office or United Parcel Service (UPS), not only provide information to customers but can also be used to monitor third-party logistics (3PL) supply chain partner performance.

Other surveys suggest that an increase in control of various components of supply chains is essential going forward. KPMG International (www.kpmg.com/) has stated that with the growing number of design centers around the world and other dispersed R&D activities, there is a growing need for better governance and controls for the R&D function (Global manufacturing...,” 2011). They caution that failure to do so can end up in tax disputes with various government authorities. To control costs, they predict a trend involving two cost-control actions: (1) collaborating more closely with suppliers, and (2) consolidating operations sites. Miller (2012) has forecast a similar trend in control consolidation. Some supply chain industry sectors, like warehousing, have found to be currently in fragile situations. This fragility is due to the inability to visualize what is happening across an entire supply chain network. They suggest to counter this lack of visibility firms need a centralized system of supply chain command and control.