9. Building an Agile and Flexible Supply Chain

9.1.1 Agile and Flexible Supply Chains

9.4 Other Topics Related to Agile and Flexible Supply Chains

9.4.1 Agility and Global Business

9.4.2 Achieving Agility with Supply Chain Synchronicity

Terms

Automated guided vehicles (AVG)

Cellular manufacturing

Change management

Flexibility manufacturing systems (FMS)

Flexible manufacturing systems (FMS)

Interactive freight systems (IFS)

Knowledge management technologies

Milestones

Quick-response manufacturing (QRM)

Sales and operations planning (S&OP)

Service-oriented architecture (SOA)

9.1. Prerequisite Material

9.1.1. Agile and Flexible Supply Chains

Agility can be defined as a business-wide capability that integrates organizational structures, information systems, logistics processes, and a philosophical orientation (Amir, 2011). Agility as a concept in planning evolved as a response to ever-increasing levels of volatility in customer demand markets. It is viewed as a market-response strategy. In situations where demand levels are unstable and the customer requirements for variety increases, a much higher level of agility is required to meet those needs. An important characteristic of an agile organization is flexibility and adaptability. To meet the challenge of demand volatility, organizations need to focus efforts on achieving greater agility such that they can respond in shorter periods both in terms of volume change and variety change. According to Amir (2011), the origins of agility as a business concept relates to flexible manufacturing systems (FMS) (for example, automated systems like the automated guided vehicles [AVG] used for quick production-line changeovers). Originally, manufacturing flexibility and adaptability were achieved through automation to smooth the progress of swift changeovers and reduced setup times. This in turn enabled a greater responsiveness to changes in product mix and production quantities.

Flexible supply chains are those that can adapt quickly to market needs and deliver products and services to customers in a timely manner. Nagel and Dove (1991) extended the idea of manufacturing flexibility to other areas of business, and from this, the concept of agility as an organizational orientation originated. One definition of agility by Yusuf et al. (1999) encompasses the notion that firms successfully explore their own competitive base on characteristics of speed, flexibility, innovation, quality, and profitability through the integration of reconfigurable resources and knowledge to provide customer driven products and services in a fast changing market environment.

Agile supply chains are the alliances of legally separated organizations (for example, suppliers, designers, producers, logistics) distinguished by flexibility, adaptability, and quick, as well as effective, responses to changing markets (Rimiene, 2011). Agile supply chains are those that utilize strategies aimed at being responsive and flexible to customer needs. While agility focuses on increased responsiveness (for example, speed of delivery) and flexibility in what is delivered, there is a costly downside to this strategy. For example, the cost of speedy delivery, like express mail, is greater than regular first-class mail. These costs are assumed to be supported by the customer who values the responsiveness. In a competitive environment, the costs are often absorbed by the seller who must look internally to reduce overall costs of the supply chain. Agile supply chains often look upsteam in their production efforts or from their suppliers to find cost reductions to support the agile response initiative downstream nearest the customers. One of the strategies often used to reduce the cost in agile supply chains is the implementation of principles of lean management (Borgstrom and Hertz, 2011). (The topic of lean management in supply chains is presented in Chapter 12, “Lean and Other Cost Reduction Strategies in Supply Chain Management.”) Lean management is often connected to supply chain agility, where tradeoffs between reducing costs (via lean management) is balanced with improved responsiveness (via agility and flexibility).

The only way to have agile and flexible supply chains is to undertake ongoing programs that move an organization toward agility and flexibility. Each step is usually undertaken as a project that needs to be managed. The systematic process of managing projects is known as project management.

9.1.2. Project Management

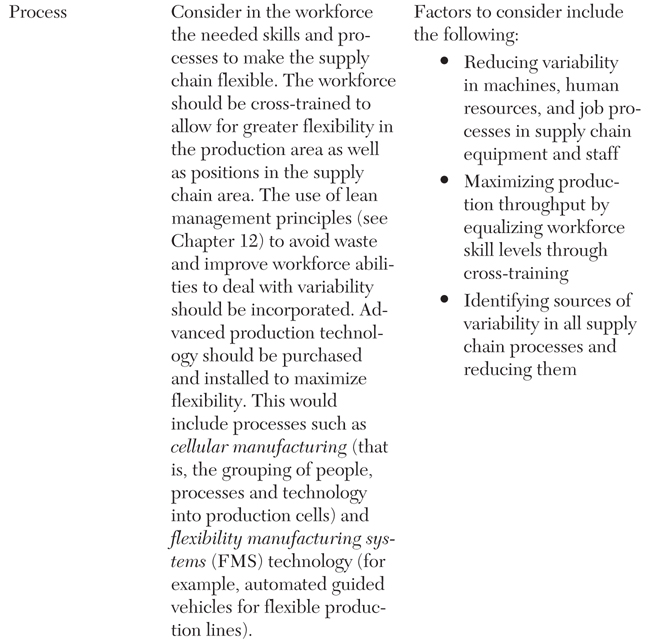

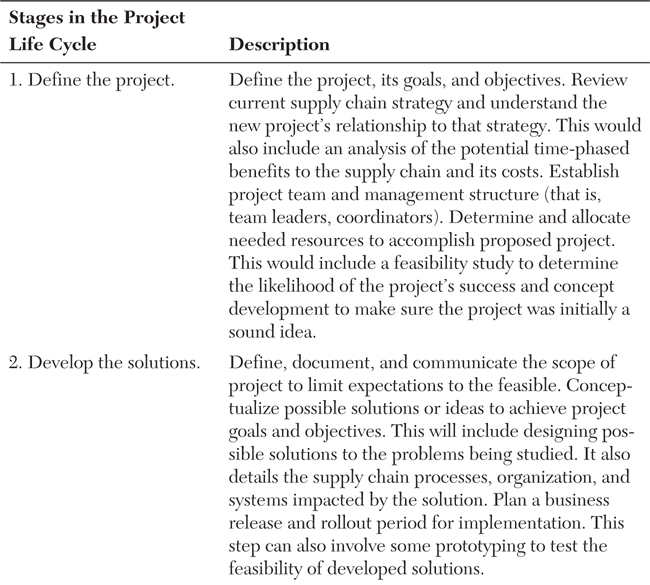

Chapter 8, “Negotiating,” examined the subject of negotiation. The act of undertaking a negotiation constitutes a project. Selecting suppliers, planning new products, and setting up budgets are all examples of projects typical to supply chain management. To manage such projects, an entire field of study has emerged: project management. Project management involves the planning, controlling, directing, and scheduling of temporary activities that are undertaken to achieve a particular set of goals (for example, establish a new policy on transportation modes) or objectives (for example, reduce production costs). Like products, there is a project life cycle that involves a number of steps over a period of time that defines what is done in a project. Table 9.1 describes an example of a supply chain project life cycle, which is the embodiment of project management.

Table 9.1. Steps in Supply Chain Project Life Cycle

Source: Adapted from Wetterauer and Meyr (2008), pp. 325–346; Matthews and Stanley (2008), pp. 24–69.

The diversity of projects that supply chain managers deal with is almost infinite, and even the general step-wise framework presented in Table 9.1 is only a simple review of basic elements that are considered in any project management undertaking. Most all projects require the services of a project manager and a project team. The project manager has the following roles (Krajewski et al., 2013, p. 52):

• Facilitator: The ability to resolve conflict between individuals and departments, to also appropriate the resources necessary to complete the project

• Communicator: The ability to communicate new resource needs and project progress to stakeholders

• Organizer and decision maker: The ability to organize team meetings, establish decision-making rules for the team, and determine the nature and timing of reports to senior management

As to the selection of project management teams, the criteria should include the following:

• Technical competence: Members need to have the ability to understand the technology required for the project.

• Sensitivity: Members need to have sensitivity to interpersonal issues that can arise in group decision making, such as the influence of senior management on junior members of the team.

• Dedication: Members should be dedicated to completing the project and be able to handle issues that might impact multiple departments.

9.2. Agile Supply Chains

Over more than 20 years, the concept of agile supply chains has evolved into a much wider range of topics as opposed to just being responsive to the market (Rimiene, 2011). Agility characteristics today include responsiveness to customer demand, responsiveness in general to any organizational need, flexibility as to what products and services are delivered, speed/time of delivery, efficiency in terms of costs, quality of product or service, cooperation with customers (both internal and external to the organization), the ability to allow and make changes in relationships of all kinds, the ability to move quickly to seize new market opportunities, and the use of knowledge management (that is, strategies and practices used in combination with computer technology in an organization to identify, create, represent, distribute, and enable adoption of acquired insights and experiences) to guide decision making (Rimiene, 2011).

How can an organization know whether it has an agile supply chain? Based on criteria established in the supply chain literature, managers should look to have or enhance the following components recognized as characteristics of agile supply chains (Harrison and Van Hoek, 2008):

• Agility in customer responsiveness: The ability to respond to the market according to customer demand and not company forecasts

• Agile network of partners: Partners who have a common goal to collaborate in order to respond to customer needs

• Business process: A view that the network is a system of business processes and not a stand-alone process, which may create penalties in terms of time, cost, and quality for the whole network

• Agile information technology: Information technology that is shared between buyers and suppliers creating a virtual supply chain that is information based rather than inventory based

Another set of criteria useful in determining whether a firm has an agile supply chain was suggested by Christopher (2). The philosophy that drives Christopher’s (2) criteria is based on the assumption that supply chains compete against one another, not their companies. Successful supply chains will be those companies can better structure, coordinate, and manage relationships with partners in the supply chain network to support better and agile communications with the customers. Christopher (2) distinguished four characteristics or criteria that an agile supply chain must possess:

• Market sensitivity: A supply chain is able to understand and respond to real demand. Many organizations continue to use forecasts, assessing the sales and supply volumes of previous years and then turning this information into stock, rather than real needs. Today, by using advanced technology, actual customer requirements are identified from data derived from fixed sales points almost as soon as the customer consumes it. An example of this is the new Coca-Cola Freestyle machines, which provide daily, per-customer actual demand usage of beverage product information that enables Coca-Cola to plan for their customer needs.

• Virtual supply chain: There is electronic transference of information between buyers and suppliers rather than inventory.

• Process integration: This involves constantly increasing cooperation between buyers and suppliers, joint production, joint systems, and information sharing to join and integrate systems with all supply chain partners.

• Network structure: This comprises a supply chain network of associated partners structured with alliances to achieve needed functions.

What justifies the need for an agile strategy? According to Goldman et al. (1995), four classic and key principles are sought in agility programs:

• Desire to increase the number of customers

• Desire to control of changes and uncertainty in the supply chain environment

• Desire to possess cooperation enhancing the competitiveness of the firm

• Desire to control supply chain participants, their information, and technology

Lin et al. (2006) found that agile companies can achieve lower production costs, increase market share, meet customer demands, facilitate the rapid launch of new products on the market, and eliminate the activities having no value added, all while increasing the company’s competitiveness. In addition, empirical research has consistently confirmed agile supply chains usually lead to successful business performance (Vickery et al., 2010).

There is a need to differentiate between an agile response to customer demand and an efficient response to demand that can be exhibited as it is related to the different stages of a product’s life cycle. As shown in Figure 9.1, an almost inverse relationship exists between the need for an agile response to customer demand and an efficient response (that is, cost minimizing). Illustrative of the need to consider product life cycles in supply chain planning over a product’s life, the agile approach is not always the best strategy to follow in every case and for every product when you look at the product life cycle. The use of agility should be matched to the needs of the product and its life cycle to maximize business performance.

Figure 9.1. Product life cycle stages and agility/efficiency implementation

Source: Adapted from Davis (2011).

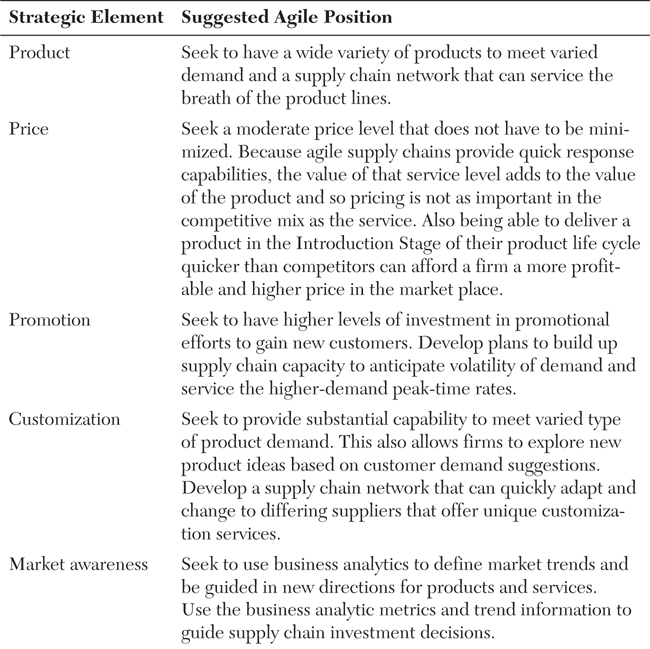

What specific strategies are used to affect an agile supply chain? Many general strategies can be incorporated into a supply chain to make it more agile, depending on the type of organization and where they can be applied. Embodying some of the criteria already mentioned in this chapter can help achieve agility, but specific strategies can be followed as they relate to specific elements. Table 9.2 describes some of those.

Table 9.2. Strategic Positions for Agile Supply Chains

Source: Adapted from Gattorna (2010), pp. 234–235; Gunasekaran et al. (2008); Krajewski et al. (2010), pp. 342–343.

What strategies are suggested for increasing supply chain agility? Identifying agile variables under the control of supply chain managers that could lead to increased agility is a good starting place to know where agility can be increased. According to Agarwal et al. (2007), managers can alter or change the following 15 variables or areas of responsibility to increase supply chain agility: recognizing market sensitivity, delivery speed, data accuracy, new product introduction, centralized and collaborative planning, process integration, use of IT tools, lead-time reduction, service-level improvement, cost minimization, customer satisfaction, quality improvement, minimizing uncertainty, trust development, and minimizing resistance to change.

Some researchers have proposed strategies for increasing agility (Gunasekaran, 1998; Rimiene, 2011; Yang and Li, 2002), including the following:

• Virtual manufacturing: Eliminating the physical structure of the manufacturing operations through, for example, outsourcing is a the strategy that enables core competency integration to achieve a more efficient operation of the company in an agile environment.

• Agile product design: Building flexibility in the product design is a strategy that allows companies to adapt to changed consumer requirements (for example, using modular product design solutions).

• Use of knowledge management: Utilizing knowledge management technologies (that is, document management systems, expert systems, semantic networks for search and retrieval, relational and object-oriented databases, simulation tools, and artificial intelligence) for innovative solutions and implementation in design and production processes.

• Mass customization: This focuses on offering customers personally tailored products and services with new technological innovations.

9.3. Flexible Supply Chain

There are differences between agility and flexibility. Gunasekaran et al. (2008) compared agile supply chains with responsive (that is, flexible) supply chains. They found responsive or flexible supply chains are more interested in supply management and minimizing costs than they are interested in agile supply chains. Flexibility in supply chains is often related to other flexibility and agility programs. For example, quick-response manufacturing (QRM) is a flexibility program that emphasizes time-reduction efforts throughout the supply chain both internally (that is, distribution and manufacturing) and externally (that is, suppliers and other business partners). With shorter lead times, a supply chain can reduce cost and eliminate non-value-added waste, while simultaneously increasing the organization’s competitiveness and market share by serving customers better and faster. Under QRM, suppliers seek to negotiate reduced supplier lead times, because long lead times can negatively impact costs such as those relating to extensive inventory, freight costs for rush shipments, engineering changes, and obsolete inventory. There is also reduced flexibility to respond to demand changes. The time-based framework of QRM accommodates the flexibility strategy, even in custom-oriented organizations. Short lead times allow a firm to respond more quickly to customer demand requirements, particularly in highly fluctuating demand markets.

What drives the development of flexible supply chains is the desire to quickly serve the customer. A number of tools can be used to implement flexible supply chains. One of the tools used to manage flexibility involves demand management (that is, various tools and procedures that enable firms to balance demand and supply in such a way as to better understand and manage demand volatility). One software solution used to accomplish this balancing is Collaborative Planning, Forecasting, and Replenishment (CPFR) (see Chapter 2, “Designing Supply Chains”). Another important flexibility and agility tool is sales and operations planning (S&OP). This business process continuously balances supply and demand. According to Simchi-Levi (2010, p. 144), S&OP is cross-functional in nature integrating sales, marketing, new product introductions, manufacturing, and distribution into a single plan. Another business process tool that can aid in matching demand with supply is known as available-to-promise. Available-to-promise (ATP) is a process that provides a response to customer order inquiries based on resource availability. Basically, it generates available quantities of a requested product and delivery due dates so that customers are aware of these ahead of time (and has the firms to supply products to meet customer demand). ATP processes consist of computer technology and usually are integrated in enterprise resource planning (ERP) management software packages (see Chapter 2).

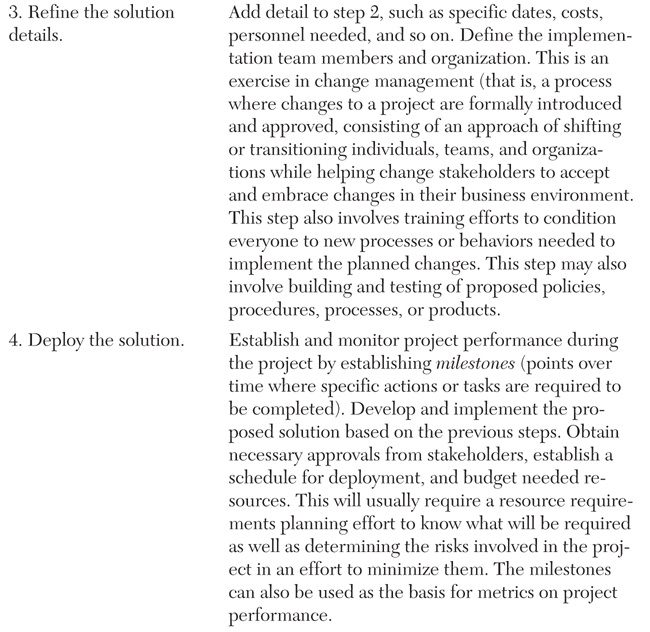

Unfortunately, even with the best demand management systems in place, customer demand can vary substantially, resulting in costly impacts. The variations in the product life cycle alone make demand planning very difficult. One strategy to deal with unexpected demand volatility is for firms to build in to their supply chains some flexibility. Where to begin to implement or improve flexibility is unique to every supply chain, but several areas can serve as starting places, including examination of three components: product, process, and system. Table 9.3 describes some suggestions for building flexibility in these areas. How much flexibility a firm should implement, suggested in the comments in Table 9.3, should be determined by perceived benefits and their respective costs.

Table 9.3. Areas for Building Flexibility in Supply Chains

Source: Adapted from Simchi-Levi (2010, pp. 133–171); Schniederjans et al. (2010, p. 51); Bowersox et al. (2007, p. 160).

9.4. Other Topics Related to Agile and Flexible Supply Chains

9.4.1. Agility and Global business

Global supply chains can be overwhelming to operate and challenging as to an end-to-end view. Butner (2011) suggests that creating an agile supply chain can be a part of a strategy that will help managers in running global supply chains, making them more manageable. Butner recommends building agile supply chain operations with the capability to respond not just to customer demands but also to demand shocks, shifts and variability, and to problems in supply production and logistics activities. Demand shocks and shifts can happen because of promotion activities. Variability in demand can cause rapid upward and downward spikes as result of many factors, including poor logistics to markets or an overly successful advertising program. Regardless of the cause, an agile supply chain needs to quickly respond to serve the needs of a global market.

To achieve a supply chain that is agile enough to deal with demand-variation issues in a global context, Butner suggests the following features be incorporated into global supply chains:

• Bundle visibility and control of supply chains into a synchronized portal like an executive dashboard (that is, a computer technology that gathers, analyzes, displays, and disseminates planning and operational data).

• Consolidate supply chain events across the entire global value chain, whether related to customers, distribution, manufacturing, or multitiered suppliers.

• Use management by exception (that is, a style of management that is focused on limiting of efforts to rule breaking exceptions, rather than routine monitoring and control procedures) to notify and recommend corrective actions.

• Use the Internet to establish collaboration with supply chain partners.

• Use service-oriented architecture and a composite business service for rapid integration of data from multiple sources. Service-oriented architecture (SOA) is an information technology architectural style that supports the transformation of a business into a set of linked services that can be broken down and accessed when needed to examine performance over an entire global network. A composite business service is a collection of business services that integrates with a client’s existing computer applications to provide a specific business solution.

• Use business analytics (that is, a combination of mathematical and statistical models and computer software systems like data mining) to guide decision making.

• Use the latest computing and communication technology to monitor and aid in controlling global components of the supply chain.

9.4.2. Achieving Agility with Supply Chain Synchronicity

According to the Journal of Commerce (2012), six core business processes must be closely synchronized to enable organizational agility. Failure to synchronize them will keep global supply chains from achieving their highest potential:

• Sales and operations planning (S&OP): S&OP should be a continuous process where executives seek to have visibility and input to reconcile short-term demand predictions with long-term organizational goals. The S&OP must occur at both the operational and executive levels, bringing views together in a closed-loop planning process that focuses on achieving consensus. The S&OP process should provide a discipline across every part of the organization, including the supply chain, establishing cadence for monitoring, and synchronizing demand, production, supply, inventory, and financial plans.

• Demand planning: Business analytics should be applied to ensure sourcing, production, inventory, transportation, and distribution functions are optimized based on a shared forecast. Business analytic solutions provide a single set of forecasts and other decision-making solutions that can be used for 24 months or longer, with each element of the plan translated into specific actions, goals, and implications for every part of the supply chain. The analytics should also account for the impact of promotional and external events that may have repercussions across any global supply chain.

• Inventory planning: Use advanced tools to create highly customized designer inventory strategies based on consumption patterns, criticality, velocity, and other key product attributes. Products are segmented on product life cycles based on other critical characteristics listed earlier. Inventory levels are managed by exception to maximize time and cost-efficiency, and wherever possible, decisions are postponed to minimize financial risk. Advanced technology solutions should be employed to consider existing, multi-echelon network complexity, lead times, costs and constraints, as well as demand and supply variability to ensure inventory plans are aligned with the rest of the global supply chain. For example, interactive freight systems (IFS) are software applications that can be used to find the least-cost routing for trucks, real-time freight tracking, including proof of delivery (POD), and freight-invoice reconciliation (Supply Chain 2020, 2012).

• Master planning: Review, analyze, and update supply plans daily to maximize customer satisfaction while protecting profits. Through a problem-oriented approach, planners should monitor performance issues and exceptions wherever they occur in the global supply network. A layered planning approach for planners to rank their business objectives and make informed tradeoffs should be used. Utilizing clear visibility into the root causes or constraints creating problems, planners should interactively adjust constraints and business rules that result in continuous performance improvements for the business overall. Despite the complexity of global supply chains, advanced technology solutions can provide sophisticated modeled capabilities to study and resolve issues of supply chain networks.

• Factory planning and scheduling: Detailed and optimized production plans based on the business analytics should be defined for plants, departments, work cells, and production lines by scheduling backward from the requirement date, while considering material and capacity constraints to create feasible and executable plans. Advanced computer software solutions should be used to streamline and align the activities of production control, manufacturing, and procurement planning teams by automating mundane tasks. The software-guided solutions should also provide time-phased reporting on key factory performance metrics, enabling planners to take corrective measures for short-term and long-term planning. Use of a management-by-exception approach can eliminate unnecessary work, minimize planning fatigue, and be useful in assessing a variety of scenarios when the unexpected occurs.

• Collaborative supply planning: Utilize advanced computer information systems for the purchase of parts and assemblies from a range of diverse and geographically scattered suppliers in a typical global supply chain. These parts undoubtedly have different lead times, demand profiles, and inventory strategies, but can be managed through customized business rules and policies that track performance exceptions based on a unique set of part characteristics. Technologies such as executive dashboards, exception-based reporting, and early warning systems can allow supply issues to be identified and resolved before they impact the global network. Today these technologies can track the entire life cycle of procured parts, enabling organizations to adjust forecasts, production schedules, transportation plans, and other supply chain activities when late deliveries or other events impact the overall manufacturing flow.

9.4.3. Agility and S&OP

In a recent survey by Supply Chain Insights LLC (www.supplychaininsights.com/) of 100 supply chain executives, supply chain agility was defined as the ability to recalculate plans in the face of market demand and supply volatility and deliver at the same or comparable cost, quality, and customer service (Cecere, 2012a). The survey identified agility as one of the three key attributes expected in any supply chain. The other attributes were flexibility and strength (that is, the ability of the supply chain to make changes). The survey went on to suggest that S&OP has in the past focused on building strength into the supply chain while ignoring the impact of flexibility and agility. It was noted that companies with the most experience with S&OP processes have been successful in adding agility to their supply chains. While the respondents in the survey overwhelmingly viewed agility as important, they rated agility-generated performance as being very low (that is, agility is important, but results from it, so far, are not). Because the firms that have been successful in using S&OP appear to have gained more from an agility strategy, the results of the survey have led to a set of five recommendations that can aid in increasing the performance of agility within corporate supply chains based on S&OP usage:

• Design agility into the supply chain based on future levels of supply and demand variability.

• Utilize S&OP to plan for unexpected demand events, and understand inherent tradeoffs as a means to explore and simulate alternative decisions based on market demand.

• Utilize employee participation in simulations to understand how to increase supply chain reliability.

• Anticipate and simulate potential supply chain disruptions for scenario explorations.

• Execute the S&OP plan, instead of making it a mere academic exercise.

9.5. What’s Next?

In 2012, thanks largely to a worldwide economic slump, corporate growth has flattened, and supply chain costs have increased. According to Cecere (2012b), 90% of businesses are grappling with skyrocketing costs, rising supply volatility, and longer supply chains that add greater risk. Factors such as commodity volatility being at its highest level in 100 years, materials scarcity, rising standards for social-responsibility programs, shorter product life cycles, and customers having higher expectations and a need for greater customization in products and services all add to a challenging supply chain environment going forward in the next five years. Also, as companies become more global, they face ever-rising supply chain complexity, demand volatility, and supply uncertainty.

Agility and flexibility are viewed as opportune strategies to deal with current and near-future supply chain challenges. In a survey by Cecere (2012b), 89% of 117 supply chain executives rated agility as being important in supply chain success, even though only about a third of the executives had the prerequisite agility to compete. The desire to catch up and narrow the gap between the recognized need and the capacity to deliver agility clearly shows that substantial interest in agility will be a future trend.

Increased interest and expansion of flexible supply chains is viewed as a major trend going forward, as well. According to Miller (2012), when time to market is more important than costs, having flexible processes and systems will be an important strategy to achieve competitive advantages.