10. Developing Partnerships in Supply Chains

10.1.1 Introduction to Supplier Relationship Management

10.1.2 Types of Supplier Relationships

10.2 Supplier Relationship Management Implementation Model

10.2.1 Supply Chain Base Rationalization

10.2.3 Relationship Management

10.2.4 Purchaser and Supplier Development

10.2.5 Supplier Performance Measurement

10.3. Other Topics Related to Developing Partnership in Supply Chains

10.3.1 Sharing Resources to Strengthen the Supply Base: Collaborative Growth Models

10.3.2 Being Perceived as a Customer of Choice

10.3.3 Ending Supplier Relationships

Terms

Cross-enterprise problem solving teams

Experienced competency

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Purchaser and supplier development (PSD)

Supplier performance management

Supplier performance measurement (SPM)

Supplier relationship management (SRM)

Supplier relationship management intensity continuum

Supply base rationalization (SBR)

Vendor-managed inventory (VMI)

10.1. Prerequisite Material

10.1.1. Introduction to Supplier Relationship Management

A firm as large as Wal-Mart depends on suppliers to have the capacity to supply the large quantities needed in its global retail operations. Other firms, such as Home Depot, need suppliers who help them differentiate by carrying distinctive brands of products. Supply chain purchasing organizations have to build the right relationships/partnerships with the right suppliers to enable them to compete with other world-class supply chains.

Developing partnerships in supply chains involves more than just the process of purchasing goods from a supplier. It involves rationalizing the supplier network that is created to serve the purchaser, manage the suppliers and the relationship that develops between the purchaser and supplier, enhance and developing that relationship, and measure supplier performance (Banfield, 1999, pp. 223–252; Carter and Choi, 2008; Monczka et al., 2011). Depending on the needs required and the level of intensity in the relationship, the entire process could be done in a few days or many years of interaction between a purchaser and a supplier. A partnership that aligns both partners to achieve a desired set of goals and that builds from a simple transactional relationship to a true partnership in business involves considerable time and effort. Ideally, the interactions lead to a trusting relationship, a partnership that helps both firms become profitable and successful in their respective industries. This is what building and developing partnerships in supply chains is all about and is the subject of this chapter.

10.1.2. Types of Supplier Relationships

Part of developing a supplier partnership is initially deciding the type of relationship a purchasing firm might need. The supply chain literature identifies at least five different types of relationships a purchasing firm can have with a supplier. The relationships are placed on a supplier relationship management continuum of intensity. Not all relationships fit neatly into a particular relationship category (see Figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1. Characteristics of differing types of supplier relationships and the SRM intensity continuum

Source: Adapted from Carter and Choi (2008, pp.238–241); Fawcett et al. (2008, p.347); Ellran (2).

Some types of relationships may be a hybrid and fall between two categories or may be some combination. The types of relationships typically fall into one or more of those defined here:

• Transactional: This is a short-term, temporary alliance or contract to provide a product or service. The supplier is sometime characterized as being at “arm’s length,” implying that a relational distance from the purchasing firm exists. Transactional suppliers simply provide an economic exchange with the purchaser. This category of relationship is usually used by a purchaser as a test to see whether a supplier can provide a least cost product or service reliably, and in doing so, determine if the firm is worthy of a more intense role as a supplier to the purchaser.

• Basic alliance: An agreement between a purchaser and supplier that does more than just provide a transaction of moving goods from the supplier to the purchaser for a fixed price, but includes participation by the supplier to undertake additional tasks or services needed by the purchasing firm (for example, vendor-managed inventory, or VMI, where monitoring of inventory levels would be undertaken by the supplier). Many competitive sources of basic suppliers undertake this type of alliance, so it is low risk and has limited impact on the purchasing organization’s overall value proposition. Purchasers and suppliers at this level share information as needed, but do not allow suppliers great access to the purchaser’s information network. Both parties know where they stand with the other. This type of relationship can be used with any supplier, and it is a prerequisite for moving toward other relationships on the supplier relationship management continuum.

• Operational alliance: This includes all the elements of a basic alliance, but there is a closer working relationship one- to three-year contract. It is one in which the supplier performs value-added services or provides additional products as part of its business. There may be some joint problem solving, but no ongoing cross-organizational team (that is, a group of individuals from different departments and organizational functional areas to bring unique perspectives to decision-making efforts). Information sharing becomes more critical because day-to-day operations must be shared for the alliance to operate successfully.

• Business alliance: Different from the previous alliances, the purchasing organization wants the supplier to provide unique or specialized products or services. Characterized by an increased recognition of mutual dependence, it is to be expected that the supplier will invest additional assets, specialized personnel, or technology to carry out the alliance. However, the purchaser will significantly reduce the supply base to commit a higher volume of business to the supplier for an extended period of time. The benefit to the purchasing organization is added value, but not strategic or core values to the organization’s business success. Some joint engineering or technology development may occur. In addition, ad hoc cross-organizational teams may be formed for joint development or problem solving.

• Strategic alliance: This alliance involves goods or services that are of strategic importance to the success of the purchasing organization and a sharing or alignment of long-term strategies for both parties. This usually involves early supplier involvement in new product/service/process idea conception and mutual recognition of a long-term ongoing relationship between the purchasing and supplier organizations. Other resources that are typically shared under this agreement include products, distribution channels, manufacturing capabilities, project funding, technology transfers, capital equipment, knowledge, expertise, or intellectual property. It is also characterized by agreements that articulate the risks and rewards and how these will be shared. Ongoing joint cross-organizational teams and top management involvement are required for strategic alliances.

As Figure 10.1 shows, the five types of relationships follow a supply chain management intensity continuum based on the intensity of the desired relationship. The differing characteristics given in Figure 10.1 are simply tendencies that have been observed in the supply chain literature. Although all supplier relationships are important, some require very close and integrated support for the client purchasing firm (that is, strategic alliance). On the other end of the continuum, transactional suppliers are firms that merely provide a fixed product or service at a fixed rate for a fixed period of time. Perhaps, if the supplier’s performance were exceptional, the firm might be considered as a candidate to move along the continuum to a higher level of usage by the purchasing firm.

Clearly, there is a spectrum of types of supplier relationships available from which to choose. It is not necessarily a goal to move every supplier from a transactional level to a more intense alliance unless there is strong mutual benefit for doing so. Also, as markets change, the appropriate alliance for a given supplier may change. Strategic alliances require active top-management participation, support, and visibility on a regular basis. However, developing partnerships with suppliers might only involve a purchasing firm helping its suppliers travel along the continuum to achieve strategic importance. All of these considerations are vital for developing supply chain partnerships.

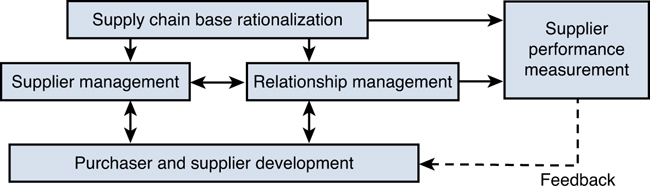

10.2. Supplier Relationship Management Implementation Model

To undertake a supplier relationship management program requires several programs that are holistically integrated to provide a continuing basis for a successful program of partnership development. These elements are listed in Figure 10.2. The implementation model suggested in Figure 10.2 is based on the literature in this field (Monczka et al., 2011; Carter and Choi, 2008, pp. 191–199; Matthews and Stanley, 2008, pp. 295–315; Fawcett et al., 2007, pp. 345–361). Let’s examine each of these five elements.

Figure 10.2. Supplier relationships management implementation model

Source: Adapted from Monczka et al. (2011), Figure 2.2, p.19.

10.2.1. Supply Chain Base Rationalization

A purchasing firm starts with an idea for a product or service and seeks to find a supplier that will help fill the need. In some situations, a supplier may be brought in just to help develop the idea in hopes of providing a continued service or product. These suppliers might have been identified when they responded to a request for information (RFI) (that is, a request for suppliers to provide information about how they might qualify to become a supplier for the purchasing firm). In other situations, a request for proposal (RFP) (that is, a document stating the desired requirements of a supplier to fulfill a particular set of product or service needs in terms of pricing or timing) might be used to find eligible candidate suppliers to join the purchaser’s supply chain team of suppliers or subsequent supply chain network.

Supply base rationalization (SBR) seeks to identify suppliers that could create significant value and contribute to a purchasing organization’s business performance. SBR is also defined as a means of determining and maintaining the appropriate number of suppliers in a supply chain network, segmented by item, category, strategic/transactional, and so on, depending on the risk and value of each segment (Carter and Choi, 2008, p. 249). SBR is a rationalization process that can involve judgmental or other quantitative means to evaluate and determine the worthiness of suppliers in terms of supplier capabilities (that is, supplier technology, quality, cost, capacity, manufacturing operations, financial strength, flexibility, and responsiveness), past performance (that is, technology contributions, price or cost improvements, quality performance, and responsiveness and flexibility to volume and scheduling needs), core competencies and match with purchasing firm’s needs, their organizational culture, and communications fit with the purchasing firm (that is, supplier’s ability and willingness to work closely with the purchaser, be culturally aligned in decision making, and the degree of risk inherent in the working relationship). In a survey by Monczka et al. (2011) leading supply chain managers viewed SBR as a foundational step in reducing the number of suppliers in a given network. The criteria on which this rationalization process is typically based includes the following:

• Seeking suppliers (both present and perspective) that are able to achieve performance improvement in terms of costs, quality or delivery in response to purchaser needs

• Seeking suppliers who can reduce administrative costs, including the reduction of the number of suppliers in the network

• Seeking suppliers who want to build a good working relationship that will create value through revenue enhancements, flexibility, responsiveness, and innovation with new products

SBR uses criteria such as these to determine which suppliers to retain, which should be added, and how many are really needed to achieve supply chain business goals. Carter and Choi (2008, pp. 188–253) suggest, and Monczka et al. (2011) observed, that during implementation of the SBR process a series of steps should be followed. They are presented here. (Note that the ordering of these steps might differ for every purchasing organization, but they are commonly used in this phase of developing supply chain partners.)

1. Evaluate supply chain base capability, performance, and effectiveness. Compare them against those of competitor purchasing firms.

2. Establish a targeted number of suppliers required in each market segment purchase category by volume, location, competitive requirements, and so on.

3. Conduct detailed supplier assessments based on criteria previously suggested and listed earlier. Analyze candidate suppliers both internally and externally through supplier self-assessments of global market possibilities.

4. Determine current and future purchasing organizations’ business situations and needs. Match those needs with the candidate suppliers in terms of volume, remaining contract commitments, and investment in specialized equipment and tooling.

5. Try to determine how suppliers will or do perceive the purchasing firm as a customer.

6. Develop goals for each purchasing segment category (from step 2) regarding economic considerations (for example, price, cost, quality) and size of the supply base. Determine suppliers to target for each segment.

7. Select and finalize the suppliers to be included in the supply chain base or network.

8. Establish a transition plan to align the suppliers in a network and implement it.

10.2.2. Supplier Management

Supplier management (SM) involves the development and implementation of ongoing supplier strategies, including short-term and long-term purchase commodity and other product category contracts (Monczka et al., 2011). For SM to be effective in improving the working relationship between the supplier and purchaser requires (1) a strategic sourcing process with commodity and supplier plans and (2) supplier performance measurements and review. The strategic sourcing process is similar to the strategic planning process presented in Chapter 1, “Developing Supply Chain Strategies.” Figure 10.3 lists the general steps involved in a typical strategic sourcing process.

Figure 10.3. Typical strategic sourcing process

Source: Adapted from Monczka et al. (2011), Figure 3.2. p. 28.

The supplier performance measurement and review requires supplier performance and capabilities to be regularly assessed and reviewed for performance deficiencies, as well as for exceeding expectations. To oversee this review process, Monczka et al. (2011), Carter and Choi (2008, pp. 191–199), and Matthews and Stanley (2008, pp. 295–315) suggest using a supplier performance management process that involves the following tasks:

• Supplier-purchaser agreement on which metrics are to be used for supplier relationship performance measurement

• Comparative analysis of progress toward strategic goals

• Consideration of problems that require addressing

• Continuous analysis of resource requirements

• Analysis of competition changes that impact the supplier-purchaser relationship and expectations

• A review of the status of the relationship and suggestions on alterations or discontinuance

• Communication on any future goals

• An analysis of overall performance of the supplier

All of these elements in the supplier performance management program should be integrated and managed holistically for maximum benefit in developing supplier relationships.

10.2.3. Relationship Management

Relationship management (RM) is the process of maintaining and developing a closer relationship between the purchaser and suppliers. When applied to the supplier side of the relationship, as it is here, the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) suggests a more appropriate term, supplier relationship management (SRM) or supplier collaboration, both of which are defined by ISM as a process in which purchasing organizations work with suppliers to accomplish common goals and objectives. According to Monczka et al. (2011), relationship management (by any other name) is based on the three fundamental elements described in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1. Relationship Management Elements

Trust is a particularly important variable in developing supply chain relationships and long-term partnerships. Ring and Van de Ven (1994) define trust as “an individual’s confidence in the good will of others in a given group and belief that others will make efforts consistent with the group’s goal.” Research on trust has shown it to be an important factor in business success, having a significant effect on many organizational activities, such as cooperation (Axelrod, 1984), communication (Roberts and O’Reilly, 1974), information sharing (Fox and Huang, 2005), reputation (Sampath et al., 2006), and performance (Earley, 1986). Depending on the nature of the supply chain relationship, different types of trust may exist. Contractual trust refers to a situation where there is an expectation that promises are kept; competence trust is the level of confidence that the partner will accomplish tasks; goodwill trust refers to the level of commitment of the partner to maintain the relationship (Sako, 1992). Araujo et al. (1999) and Choi and Krause (2005) have found that it is the existence of goodwill trust that enables supply chain managers to fully integrate processes and develop cooperative learning mechanisms and governance structures.

10.2.4. Purchaser and Supplier Development

Purchaser and supplier development (PSD) is focused on identifying and correcting the approaches, practices, and beliefs that limit supplier effectiveness and competitive performance on behalf of the purchaser. Fawcett et al. (2007) suggested and Monczka et al. (2011) confirmed through research that to develop relationships between the client purchasing organization and suppliers, supplier capabilities must meet the purchasing firm’s market needs. The PSD program of SRM helps to identify and overcome both performance capability limitations and the obstacles both parties may have in working together. The research by Monczka et al. (2011) that explored what firms are doing in PSD programs revealed they utilized business analytics (that is, results and analysis of surveys from both purchaser and supplier) to determine problems areas and opportunities for improvement in working relationships. The firms were also observed to have made resource commitments to PSD. In addition, PSD programs were marked by substantial joint efforts toward improving purchaser and supplier capabilities, products, processes, and working relationships. To implement these joint efforts, improvement workshops were developed and used to focus on cost-effectiveness related to value analysis, value engineering, innovation, manufacturing excellence, design specifications, policy improvements, and purchaser and supplier processes.

10.2.5. Supplier Performance Measurement

Supplier performance measurement (SPM) involves measuring supplier performance as it relates to SRM. The instruments used to measure supplier performance include surveys of opinions on supplier performance and interviews with internal client purchasing firm managers. In addition, supplier and supply scorecards (that is, a rating system on specific criteria important to a supplier’s performance) used in the evaluation process were also found to be useful for measuring ongoing performance. Metrics found beneficial for measuring supplier performance reported in the literature include financial, operations, internal and external customer orientation, and innovation measures. Other metrics commonly used in this element of SPM typical to supply chain management include cost and price improvement, quality, delivery, flexibility, responsiveness, and the use of technology.

Of critical importance is whether the SRM efforts have had a positive impact as measured in an SPM program. In the study by Monczka et al. (2011) several recommendations for SPM were suggested as means to enhance SRM, including the following

• Establish key performance indicators (KPIs) using metrics such as cost reduction, technology improvement, innovation, on-time delivery, responsiveness, and flexibility. Then evaluate performance on collaboration projects with targeted return-on-investment goals.

• Encourage both purchasing and supplier firms to utilize cross-functional teams on joint cross-enterprise problem-solving teams (that is, problem-solving teams composed of individuals from differing organizations, like external suppliers and the purchasing firm’s executives). Establish metrics to ensure an equitable amount of resources are committed to joint projects by both parties.

• Ensure risks and rewards are equitably shared by purchaser and suppliers. Make clear in communications how both parties will benefit from efforts to improve efficiency.

The use of SPM plays a pivotal role in SRM in that it provides feedback to the purchaser and supplier development program (see Figure 10.2) as to where they can impact and change the SM and RM programs. Also, the RM program feedback to the SPM allows for a closed-loop process of monitoring change and advancement in the supplier relations management program.

10.3. Other Topics Related to Developing Partnership in Supply Chains

10.3.1. Sharing Resources to Strengthen the Supply Base: Collaborative Growth Models

Suppliers can go out of business and thus cause difficulties for purchasing firms. Sometimes just a little financial or other expertise might be able to help keep the company from going under. Arnseth (2012b) suggests that during economic downturns it is good business for purchasing firms to undertake support for troubled key suppliers with funds or expertise. Such practices are observed in industry today. Referred to as a collaborative growth model (that is, purchaser supports needy supplier with shared resources), purchasing organizations reach out to key suppliers that may be having difficulties (for example, cost related, operational related, financial) and share resources of personnel, equipment, and finances to strengthen and build up their suppliers. These are not just acts of kindness to the supplier by the purchasing firm, but are viewed as a mutually self-serving source of benefits for the supplier and purchaser as well.

Going back to the 1970s and 1980s in the United States, it was not uncommon for purchasing firms and suppliers to work closely together to implement programs for mutual benefit, such as the principles of just-in-time management (Schniederjans, 1993, pp. 33–38; Schonberger, 1982, pp. 157–180). According to Arnseth (2012b), collaborative growth models are focused on building both purchaser and supplier. For example, a supplier that needs greater financial strength might be given the opportunity to enter into a revenue sharing model with the purchasing organization to strengthen the financial situation. Such a model might be perceived by banks and other financial institutions funding the supplier as a stronger revenue position than just selling goods to a purchaser. Ways purchasing organizations currently add resources back into their supplier organizations to build, strengthen, and add value to them include the following:

• R&D support

• Quality-improvement support

• Purchaser-paid tuition and educational expenses for supplier personnel to attend conferences to learn current trends and technology

• Financial support for supplier loans

• Purchaser cash payment policies to help guarantee a supplier’s payment

• Use of purchaser’s supply chain to help build the supplier’s supply chain infrastructure and explore new markets for further growth

• Accelerated payment program to suppliers to help those who are undercapitalized continue in business

• Purchaser provided teams of experts to suppliers to improve their efficiency (and reduce or hold costs down for both parties)

• Joint research in technology developments with both first- and second-tier suppliers

10.3.2. Being Perceived as a Customer of Choice

In times of crises, there is great value in being considered the top-priority customer of a supplier. According to Day (2011), the importance of price does not ensure a supplier will automatically guarantee the purchaser as customer of choice (that is, a term used to describe the highest ranking by suppliers of the desirability to do business with a purchaser). As previously discussed in this chapter, SRM activities begin with the segmentation of a supply base into categories such through tiers, strategies, products, and so forth. A similar approach is taken on the sales side when looking at a customer base using key account management (KAM) (that is, candidate customers of choice). Suppliers the three main elements to select key accounts:

• Financial benefits: Past, present, and potential for superior revenue income streams.

• Customer requirements: The alignment of the purchasing organization’s goals and objectives with the supplier’s vision and objectives, including factors such as the length of time in the relationship, perceived trustworthiness. and the number of competing suppliers.

• Customer attributes: The factors and behavior that a purchasing organization signals to the supplier as to whether the firm is viewed as a trusted partner. These include transparency in information sharing, openness to ideas, a willingness to collaborate and reward the supplier for value, access to purchasing executives, brand and market share, and efficient decision making.

The survey of 400 suppliers reported by Day (2011) identified what suppliers view as important and what is of less importance in their relationships with purchasers (that is, identifying purchaser as a candidate customer of choice):

• What key suppliers value the most: Profitability, alignment of supplier business strategy, revenue (that is, actual and potential), alignment of technology and innovation, and long-term perspective

• What key suppliers value the least: Length of relationship, purchaser’s speed of decision on purchases, and purchaser’s ability to execute orders

Notice that although profitability and revenue are important, other, less-tangible factors are also important and represent opportunities for relationship development. Strengthening the perception of what suppliers view as important is one way to move an organization from being one of many to a customer of choice.

10.3.3. Ending Supplier Relationships

Terminating a supplier relationship can happen for many reasons. A purchasing organization may have a change in strategic direction and may no longer need a particular supplier. More commonly, the product life cycle may be nearing its decline stage, necessitating a product’s discontinuance. Other reasons might include a supplier that no longer is able to have access to a particular material or product, which a purchasing organization needs, or that the working relationship simply no longer works.

Mitchell (2012) suggests that a number of important issues need to be considered in the decision-making process before ending a purchaser and supplier relationship. Some of these issues are presented in Table 10.2. As Mitchell (2012) suggests, purchasing organizations should try to end strategic supplier relationships on a positive note, because a supplier ending a relationship today might be a supplier for the same firm in the future.

Table 10.2. Issues to Consider When Ending Supplier Relationships

Source: Adapted from Mitchell (2012).

10.4. What’s Next?

What’s next involves what a purchasing firm is willing to do to move its SRM efforts toward a true partnership. Recent research has reviewed what firms with SRM programs are doing either to begin SRM programs that will build supply chain partnerships or to move a firm’s SRM program to the next level (Arnseth, 2012a; Carter and Choi, 2008, pp. 189–200; Monczka et al. 2011, pp. 38–39; Smith 2011). Using the criteria listed on Table 10.3 as a quality checklist, it is possible to move suppliers along the SRM continuum in Figure 10.1 to achieve a closer partnership. The listing in Table 10.3 should be viewed as a qualification process to know whether a purchasing firm is ready to achieve organizational excellence in SRM. Not all firms can or even want to do everything on the list, but the closer the firm exhibits the checklist suggestions in Table 10.3, the closer it will move toward excellence in SRM.

Table 10.3. Checklist for Excellence in SRM

Source: Adapted from Arnseth (2012a); Carter and Choi (2008, pp. 189–200); Monczka et al. (2011, pp. 38–39); Smith (2011).