7. Aligning Supply Chains to Meet Life Cycle Customer Demands

7.3 Aligning Supply Chain Resources

7.3.1 Alignment and Integration

7.3.2 A Technology Approach to Aligning Supply Chain Resources

7.3.3 Synchronization of Supply with Demand

7.3.4 Strategic Alliances and Alignment

7.3.5 Using a Supplier as an Alignment Partner to Meet Customer Demand

7.3.6 Optimizing Life Cycle Production with Produce-to-Demand

7.3.7 An Academic Perspective on Alignment

7.4.2 Dealing with a Logistics in Seasonal Growth Surge

7.4.3 Contingency Planning as a Growth Strategy

Terms

Collaborative planning, forecasting, and replenishment (CPFR)

Electronic point of sale (EPOS)

Qualitative forecasting methods

Quantitative forecasting methods

Voluntary Interindustry Commerce Standards Association

7.1. Prerequisite Material

Demand fluctuations that are not anticipated from forecast expectations are a constant challenge for supply chain executives. In the Introduction Stage of a product’s life cycle, customer demand is at best a risky situation, particularly for new types of products that have no history from which to forecast accurately. In the Growth Stage of a product life cycle, there are also risks. Sometimes a rapid growth in demand can signal a positive event and a successful product. Unfortunately, too rapid growth can have negative impacts on a supply chain. When growth in demand exceeds the capacity of a supply chain to handle the needs of customers, it offers a great challenge to chase after the demand. Also, as a product enters its Maturity Stage, there is some stability in supply chain planning, but as demand levels off there are pressures to reduce costs in an effort to increase sales. If the product’s sales suggest it is in a Decline Stage, other complications occur in planning the discontinuance of a product. Supply chain managers must be able to align and realign resources to meet the unique demand requirements of all stages of a product’s life cycle. The more closely those resources are aligned with actual customer demand, the more efficient and effective the supply chain.

What causes unexpected variations in demand can include a variety of factors. Promotional actions (for example, reduced pricing, special product offers), competitor actions (for example, increase product prices) and newly introduced products that take off beyond what is expected (because there is no history on which to base a forecast) can all lead to unexpected variation in customer demand.

A prerequisite planning effort to anticipate and prepare for the possibility of variations from planned to actual demand is called demand planning. Demand planning is concerned with fulfillment of customer demand. From the perspective of supply chain management, this involves knowing the customer’s product needs and when and where needed. This involves forecasting efforts to project customer requirements and installation of control measures to ensure the customer is in fact receiving the products and services they need. Basically, the demand planning can be divided into three functions: structures, processes, and control (see Table 7.1). The planning structures require understanding each product’s demand time horizon so that each phase of demand (over the product’s life cycle) can be matched with supply chain capacity capabilities. This includes consideration of demand in geographic areas where demand is distributed from supply chain partners (into and out of manufacturers, distributors and so on), as well as supply chain considerations for aggregating product lines for logistic reasons (for example, shipping full truck loads of multiple products from a single product line).

Table 7.1. Demand Planning Functions

Source: Adapted from Kilger and Wagner (2008), pp. 133–160.

Once the product and geographic distribution of demand are understood, a process to generate the forecasts must be selected. We can divide forecasting methods into two types: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative forecasting methods are based on mathematical formulas. Commonly used quantitative forecasting methods include time series analysis, regression analysis, and simulation. Common qualitative forecasting methods are based on judgment, opinion, experience, consensus, and other subjective measures. They can include the Delphi method and market research. Time series methods are statistical forecasting techniques that use historical data to predict the future. There are many time series methods such as moving average, weighted moving average, exponential smoothing, regression analysis, and Box Jenkins technique, to name a few. Regression forecast methods attempt to develop a mathematical relationship between demand and the factors that cause it in an effort to explain why the relationship behaves the way it does (for example, competitor pricing, economy). Simulation forecast methods are used in decision making (for example, forecasting) under risk, where variables that impact customer demand follow a probability distribution (for example, likelihood of high demand during economic properous times versus low demand during downturns in the economy). Simulation forecast methods allow the forecaster to make assumptions about the condition of the enviroment that impact customer demand. Market research is a systematic forecast approach using field surveys or other research methodologies to determine what products or services customers want and will purchase and to identify new markets and sources of customers. The Delphi method involves obtaining insightful judgment and opinions from a panel of experts using a series of questionnaires to develop a consensus in forecasting.

Which methodological process can be used will depend on the environmental aspects of a decision situation and on the particular planning task. For example, different approaches may be appropriate for different stages of the product life cycle. At the preproduct development Introductory Stage, the Delphi method or market research forecasting techniques may be the more appropriate means of analyzing forecast demand trends. In the life cycle Growth Stage, where rapid demand growth is experienced, quantitative methods for short-term forecasting (for example, averaging or exponential smoothing averages) may be appropriate, whereas the market Maturity Stage of the life cycle might require the use of regression models to estimate trends and longer-term cyclical variation. Where customer demand forecasts are inputs to decisions about inventory in the supply chain, the forecasting horizon is often short term, and historical in-house data might be used. In contrast, when customer demand forecast is used as an input to a capital investment decision such as a plant or machinery, the forecasting horizon is longer term, and the forecast may be qualitative rather than quantitative. Supply chain managers often utilize a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods in these situations.

Once the forecasts are prepared and released to management for implementation, planning control activities should be undertaken. These include monitoring the forecast values against actual demand behavior on a continuous basis. These accuracy measures can be simple variance statistics that are integrated into management information systems or enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. Commonly used variance statistics in forecasting accuracy metrics include the mean average deviation (MAD) (that is, the mean difference between actual and forecast demand) and mean square error (MSE) (that is, mean squared difference between actual and forecast demand). Many firms establish a simple unit difference threshold (that is, minimum unit demand needed to denote a problem or justify the continuance of a product) to bring attention for corrective action. Because of the number of products most supply chain managers handle, information systems use measures like these to trigger exception reports to the appropriate manager and even the appropriate outside supply chain partner. If exceptions like rapid growth are observed from the planned forecast, actions are taken to align supply chain capacity to meet the spurious demand requirements.

7.2. Demand Planning Procedure

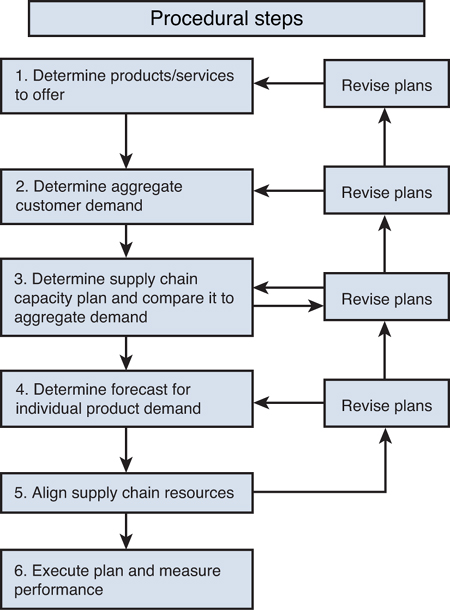

Before supply chain managers can align their resources to serve customers, they must learn what customer demand will be. This demand information can be derived by the demand planning procedure suggested in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1. Demand planning procedure

The steps in this procedure can be characterized as follows:

1. Determine products/services to offer: Factors to consider include products or product lines that are new products in the Introduction stage of their product cycle and others in a Decline Stage that are being discontinued or eliminated. The same is true of services offered in supply chains to partners. This step seeks to determine the types of products/services to offer. Extending from strategic planning percentages in expansion or contraction of a firm, aggregate planning of customer demand can begin from a simple percentage increase or decrease in total product/service offerings. This step is heavily dependent on marketing intelligence and executive judgment to guide the selection of new products that will be winners and older products that will be losers.

2. Determine aggregate customer demand: Based initially on statistical forecasts, but modified by judgmental input, total expected demand is estimated. The idea is to come up with a general expectation of total product/service demand that can be used to guide longer-term decisions for the organization as a whole (for example, office and facility leasing requirements, total labor needs). This would be the aggregate demand plan for the entire organization.

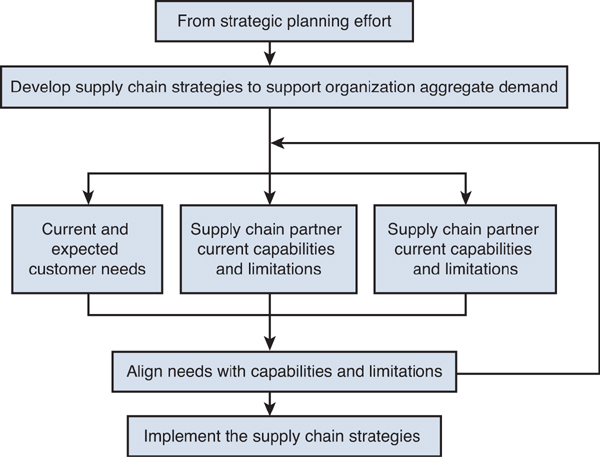

3. Determine aggregate supply chain capacity and compare it to aggregate demand: This step requires an estimation of aggregate supply chain capacity capabilities. This is accomplished by auditing supply chain partners from historic behavior in contractual partnerships. This step is tied to the procedure discussed in Chapter 1, “Developing Supply Chain Strategies” (refer to Figure 1.7 from Chapter 1), on developing supply chain strategies. The components of this step are further delineated in Figure 7.2. This permits decision making at an aggregated level of planning. Planning decisions, like increasing total staff by some percentage for growth or the acquisition of new facilities, can be supported by the information gleaned at this step in the procedure. This may be necessary because of capacity limitations to revise the aggregate demand estimates down or even to reduce the number of products the firm is planning on offering. One of the methodologies that can be used to compare aggregate demand with aggregate capacity is rough-cut capacity planning (See Jacobs et al., 2011, pp. 244–253).

Figure 7.2. Determining the supply chain capacity plan

4. Determine forecast for individual product demand: To plan any product’s future demand requires disaggregation down to a product line and to the individual product. This is because of the nature of a product’s life cycle that impacts product demand. As explained in Chapter 1 (see Figure 1.5), aggregate product demand can be made up of many individual products in various stages of a life cycle. Adequate forecasting for purposes of aligning supply chain resources often requires individualization of product demand. Computer generated statistical estimations are commonly used here. In addition, subjective methods are often used to update and adjust statistical forecast values of customer demand. The greater the need for judgmental adjustments to forecast demand, the greater is the effort invested to ensure accuracy. In this step, it is not uncommon to use consensus forecasting methods (that is, a group of experts pool opinions on forecast demand values). The outcomes of all these estimations are the necessary forecast values of individual product and product-line customer demand.

5. Align supply chain resources: This step begins by disaggregating the aggregate supply chain capacity from step 3 and relating or allocating it to fulfill the individual product demand requirements from step 4. The alignment might require a revision in all of the prior steps depending on the ability of the supply chain planners to meet the individual customer demands. Suggestions on how to align supply chain resources will be discussed in the following sections of this chapter.

6. Execute plan and measure performance: After the supply chain resources have been aligned to achieve specific objectives, the plan to meet customer demand should be launched. In addition, short-term metrics should be established, data collected continuously, and results monitored to compare planned versus actual performance.

How often this demand planning procedure is repeated depends on the firm planning policies and the volatility of demand in the industry. It is advisable to have supply chain managers meet with sales and other operations managers frequently (for some firms weekly) to discuss market demand and capacity planning alignment issues.

7.3. Aligning Supply Chain Resources

Aligning supply chain resources can be viewed internally and externally. Alignment of a firm’s internal supply chain resources refers to the alignment of the organization’s own internal resources. It is expected supply chain managers will do so within the context of improving efficiency of their own operations. In most of the literature, the topic of alignment of supply chain resources is focused externally on the partners that make up the supply chain network that the organization uses. While both internal and external organization alignments are important, our discussion focuses mainly on the external supply chain partners and how their efforts help align the external supply chain, which consequently impacts the internal operations of supply chain organizations.

7.3.1. Alignment and Integration

According to Siegfried (2011), supplier alignment is defined as the alignment of the supply organization’s and the supplier’s vision, goals, and strategies to ensure consistency of direction and objectives. The definition for supplier integration is a management activity that combines resources and capabilities of supply management with those of key suppliers to achieve a competitive advantage. When you align and integrate at the same time, you can develop a powerful competitive advantage. This can be accomplished by suppliers who align their business strategies, visions, and goals with the firms to which they provide supplies. Under this scenario, as supply management firms grow, so too do their suppliers. Some of the tactics to implement this approach include building relations, roadmapping technology, and seeking a good fit with suppliers:

• Building a relationship: A work-share agreement (that is, suppliers agree to produce a product that is interchangeable with those manufactured by the supply management firm that employs them) can be a useful tool in developing an aligned and integrated strategy. By closely sharing production and engineering information, firms like Rolls-Royce are aligning their production capacity for longer-term business strategies and building a workable base for further collaboration (Siegfried, 2011). Rolls-Royce understands and works with some of suppliers to help them deal with the cyclical nature of their workload. This permits Rolls-Royce to help balance the suppliers workload during their up and down demand periods and thus strengthens them. This is important to Rolls-Royce because of the need for capacity over the longer term of products whose life cycle is substantially longer than most.

• Roadmapping technology alignment: If suppliers are to serve their customers, a commitment requiring close integration and alignment of technology is essential. For suppliers who want to align themselves with a supply management firm, the supplier should demonstrate commitment by investing in technology that enhances communication. This requires the supply management firm to ensure the supplier’s business model and business strategy is aligned with them and that the supplier has the financial stability and capabilities to afford the investment and maintenance. Equally important is a commitment from the supplier to invest in growth to support the supply management customer. Siegfried (2011) reports that Rolls-Royce does all this by working closely with suppliers to get them to agree to an integration technology plan. The alignment with suppliers involves roadmapping the timing of technology investments for all partners to ensure information sharing and understanding of where each organization is going in terms of technology investments.

• Seeking a good fit with the supplier’s business model: Some suppliers seek a quick turnaround on products they produce on a transactional basis; others have a business model where longer-term relationships are essential to reap the financial benefits needed to make a relationship worthwhile. Some suppliers invest in dies that are disposable and used for a single production run and are then discarded. Other suppliers invest in dies that are more costly and are engineered to last decades. The business model of a supply management firm should be aligned with the business model of the suppliers for the type of products and services they require. There has to be a good fit between the business models of the supply management firm and their suppliers.

Aligning and integrating the supply management firm with their suppliers can be time-consuming and costly, but also can have many benefits. Some of the benefits reported in the literature include improved delivery, elimination of waste, improved innovation, lower costs, improved supplier stability, quality improvement, and better risk management (Siegfried, 2011).

7.3.2. A Technology Approach to Aligning Supply Chain Resources

Software technology exists to support the communication that is vital to aligning supply chains in a timely manner. Collaborative Planning, Forecasting, and Replenishment (CPFR) (also mentioned in Chapter 2, “Designing Supply Chains”) is software that seeks to integrate supply chain partners, including their customers (Jacobs et al., 2011, pp. 46–52). It was developed by Voluntary Interindustry Commerce Standards Association (www.vics.org/) to improve the competitiveness of retailers in fast-paced demand situations in terms of both cost and delivery performance. CPFR seeks to reduce the variation between supply and demand for individual products by making organization changes. The software seeks to change both customers and supplier partners to improve communication and collaboration by aiding in the development of new business processes for creating forecast information so that it can be shared on a daily basis. This software helps trading partners work together to reduce forecasting errors and increase product availability by improving the synchronization within a supply chain for inventory replenishment. In addition to building trust with supplier partners, this software is credited with reducing inventory and improving in-stock product availability (Sherer et al., 2011). To successfully implement this kind of system requires a commitment to cooperate with supply chain partners in planning, sharing information, and a coordinated fulfillment strategy. The software actually forces collaboration of partners. In doing so, it permits timely information to everyone to coordinate resources and align them to better serve customers throughout the supply chain.

By using CPFR, timely information allows supply chain partners to update inventory information for replenishment, saves sales, provides better delivery services, and allows partners to align inventory resources more efficiently. Also, the constant updates on forecasts and the ability for collaborative help to generate consensus forecasts are of benefit throughout the supply chain. This permits partners to align and realign production and supplier based decisions avoiding waste in production and unwanted inventory.

7.3.3. Synchronization of Supply with Demand

Goldratt and Cox (1984) espoused the notion of synchronous manufacturing, which refers to the production processes working in harmony to achieve a profit goal for the firm. The idea is that when an entire manufacturing facility and its processes are synchronized, the emphasis can be on total system performance and not on optimizing individual components, which might suboptimize the overall performance of the facility.

Supply chain synchronization means all elements that make up a supply chain are connected and move together to avoid waste and achieve timing requirements for all partners (Christopher, 2011, p. 141). In the same way that two people can dance beautifully together, so too must the partners in a supply chain move together to achieve service performance objectives. The way firms are connected in supply chains is through information sharing. The kind of information shared includes customer demand and supplier capacity information. To achieve the needed degree of information visibility and transparency requires substantial process alignment of communication technologies and a willingness of all partners to share necessary information upstream and downstream.

Several tactics can be used to help implement a synchronous supply chain strategy:

• Set early identification of shipping and replenishment requirements

• Ship smaller shipments, but more frequently

• Look for ways to consolidate inbound shipments

• Implement quick response (QR) logistics supported by technology (for example, bar coding, electronic point of sale [EPOS] systems with laser scanners) to speed information from customers to manufacturers and other suppliers

A synchronized supply chain is both responsive to the customer and to supply chain partners. While making the product available to the customer, this strategy minimizes the amount of inventory, providing immediate information and an ability to quickly identify where the supply chain needs alignment to better serve the customer.

7.3.4. Strategic Alliances and Alignment

A strategic alliance can be defined as a temporary agreement between two or more organizations that have a joint interest in accomplishing a specific task. They are willing to pool some resources to analyze the task. A strategic alliance is a generic phrase encompassing most forms of collaborative relationships. Although many relationships are not technically considered an alliance (for example, supplier-purchaser relationship), they can become an alliance when both parties incur some form of risk (for example, financial loss, quality image risk) connected to their strategically important interests. Strategic alliances are meant to be flexible agreements (almost relational rather than contractual) to permit both parties to work together on a particular problem or issue. They are a means by which differing types of businesses, governments, and even competitors can temporarily join financial, technological, process, and personnel resources to permit a common problem, issue or complication to be studied.

There are two types of strategic alliances: nonequity and equity. A nonequity strategic alliance involves little investment of financial equity. Examples include two firms entering into an R&D cooperative effort or consortium (for example, designing a new product for both firms), making technology swaps (for example, trading technology between firms that own patents and want to avoid paying royalties), entering into a joint product development agreement, or having informal alliances that bring staff together from differing firms to study supply chain problems.

An equity strategic alliance is a more formal agreement that involves a substantial commitment of equity (for example, financial, technology, property) from both parties. It is often more enduring and tends to be focused on results. These alliances are often structured with complex legal and contractual agreements. Examples of an equity strategic alliance might include joint ventures, joint equity swaps, and affiliates. Joint ventures are temporary partnerships in which the resources of two or more organizations are combined to form a separate new business entity. The legal form of the new business might be a new corporation or just a contracted entity of limited duration. Joint equity swaps are similar to joint ventures, but no new organization is created. Instead, the parties simply exchange or swap equity ownership. Affiliate joint ventures have even less formal equity transactions than the joint equity swap. Here one of the parties simply takes some form of equity position with regard to the other. An example is where Chrysler took a 25% stake in Mitsubishi Motors when Mitsubishi agreed to develop and produce an engine for the Chrysler’s E-Car during the 1980s.

Alignment advantages for supply chain managers in using strategic alliances include the following:

• Enhances organizational skills: Alliances allow for a great deal of shared information and opportunities for organizational learning. Suppliers can learn from supply management firms and vice versa.

• Improved operations: Alliances can result in lowering system’s costs and cycle times. Firms can join together to better utilize off-season capacity by forming an alliance of firms not in the same industry.

• Improved financial strength: Administrative costs can be shared between allied firms, reducing expenses and increasing profitability. This, in turn, can improve both firms’ financial positions.

• Enhanced strategy growth: New partners can provide access to business opportunities that would otherwise have high entry barriers. Alliances allow firms to pool expertise and resources to overcome barriers and explore new opportunities.

• Improved market access: Partnerships can lead to increased access to new market channels, particularly when partners’ markets do not complement each other.

7.3.5. Using a Supplier as an Alignment Partner to Meet Customer Demand

Suppliers can be used to change supply management firms by helping them align their current or new businesses to better meet customer demand. When a supply management firm needs to change its business model because it is introducing a new business channel or is having problems with an old one, suppliers can be engaged to help in the transition. An example of this type of collaborative arrangement is illustrated by the actions of Wehkamp.nl, the largest Dutch online retailer of home goods, technology, and apparel in the Netherlands. In recent years, according to Cooke (2011), Wehkamp.nl’s combined model using both online sales and a more classic catalog business caused problems. Timing between weekly inventory ordering and replenishing (which worked fine for the catalog business) caused lost sales in the online business because customers were not willing to wait for orders. Wehkamp.nl needed to move from a weekly to a daily replenishment system and from a push model to a customer pull model.

To accomplish the transformation process, they turned to their best supplier, ETC, a wholesaler (Cooke, 2011). The two companies agreed to a pilot project where ETC would perform a vendor-managed inventory (VMI) role by assuming responsibility for keeping the right items in stock at Wehkamp.nl’s warehouses. In addition, to make the daily replenishment possible, supply chain partners were required to acquire software that would determine appropriate levels of inventory needed. The software calculated stocking levels based on customer pull, as well as gave supply chain planners strategic, operational, and technical perspectives on inventory levels.

This project proved to be so successful that within three months Wehkamp.nl made this a permanent way of their doing business. The enhanced inventory replenishment systems fueled a rapid growth rate and provided the firm with excess capacity to deal with its growing online business. In addition, it enhanced sales by providing the right product at the right time to the customers, while minimizing total inventory and safety stocks. Reduced inventory freed up capital, which allowed Wehkamp.nl to expand its product lines.

7.3.6. Optimizing Life Cycle Production with Produce-to-Demand

In the ups and downs of a product’s life cycle, product demand can change almost daily. As a result, the potential for products to linger in supply chains taking up valuable space and financial resources until demand meets up with them or they are written off as a loss is common. As lean experts advocate, any product that is not moving in a supply chain is generating a variety of waste (Myerson, 2012; Schonberger, 2010). The firms that are lucky enough to be able to use a product-to-demand strategy avoid much of this waste.

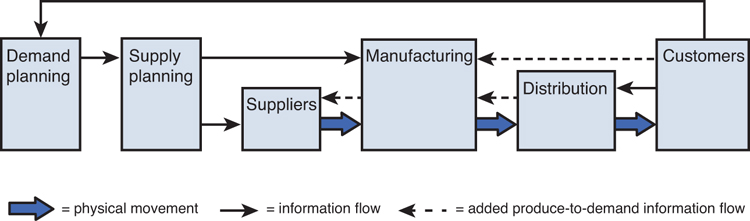

As illustrated in Figure 7.3, there are differences between the make-to-stock strategy most supply chain organizations utilize and the produce-to-demand strategy. Chiefly the difference is that the produce-to-demand adds information sharing between customers and distribution centers with the respective manufacturer. The result of these added interactions, according to Schutt and Moore (2011), is less inventory waste in the chain. To make this strategy happen requires some classic just-in-time changes to the way production is undertaken (Schniederjans, 1993; Schniederjans and Olson, 1999), examples of which include more timely scheduling (for example, a time frame from daily to hourly), smaller production quantities, and help from suppliers to manage inventory.

Figure 7.3. Comparison of make-to-stock and produce-to-demand systems

Source: Adapted from Schutt and Moore (2011) Figures 1 and 2, pp. 56–57.

Many firms that operate under the make-to-stock strategy may be able to change over to or at least move toward a produce-to-demand strategy. To determine whether a firm is a candidate for this approach, Schutt and Moore (2011) suggest four factors be in place:

• Production technology: Reliable production technology is needed as the firm moves to a short-cycle production of finished goods. Reliable information is needed to accurately fit demand requirements with production capacity. Flexibility in production capacity and the ability to reduce set up times are necessary requirements

• Product characteristics: Some products are more suitable for produce-to-demand than others. Products that have a short lapse from the time a decision is made to manufacture a product until the product is available to ship are best. Others include high-volume products (for example, manufacture of paper) and products that have few components. Products that have long-term processes (for example, fermentation) are not good candidates. Ideally, necessary raw materials and finishing elements (for example, packaging) must be readily available.

• Supply chain organization: Suppliers should take on most of the responsibility for maintaining component inventories. There is a need for quick response to demand needs, necessitating the formation of strategic and collaborative procurement relationships.

• Information visibility: Sharing customer information with distributors, the manufacturer and suppliers (see Figure 7.3) is essential to make customer demand and finished goods inventories visible for plant schedulers on a real-time basis.

Building on these prequalifying conditions, Schutt and Moore (2011) suggest candidates for produce-to-demand should face and be prepared to make changes in their manufacturing capacities, production reliability, changeover times and costs, component rationalization across products, supplier relationships, and technology that support near-real-time customer order and inventory information. In addition, potential candidates for produce-to-demand should consider four related issues.

• Changing production planning and scheduling processes: Changes in master production scheduling (MPS) efforts might include planning against lower finished goods inventory targets, planning more frequent production of smaller batch quantities, and reducing the number of planning horizon days. This moves the MPS from the status of an exact plan to basically a guide that permits greater flexibility under a produce-to-demand strategy. In addition, plant-level planners will have to watch daily customer order streams and redevelop short-term schedules to better match production with demand.

• Rethinking inventory policies: Reducing inventory is the main objective in using this strategy, and part of that effort involves recalculating safety stock, cycle-stock levels, work-in-process (WIP) levels, and materials inventory policies to take into account shorter lead times.

• Improving supplier communications: There is a need for frequent communication with suppliers. Inventory items that are needed for production in large quantities and those that are unique to each finished goods must be closely managed to flow through the production facility so that there is very little lead time. (Schutt and Moore suggest one day or less.) To achieve the intensity of monitoring these inventories require, there is a need for good software tools. Communications-oriented spreadsheets posted on shared Web sites that show daily or hourly delivery requirements and actual current materials status are suggested as a means to augment communication. The same information can be shared via smartphones and other telecommunication devices to enhance the speed of delivery.

• Aligning the organization: To make the produce-to-demand strategy happen requires realignment of the manufacturing organization, moving it from a cost minimizing, department centered orientation to a supply chain orientation. In manufacturing-oriented firms, production cost per unit has been the major metric for evaluation. In a produce-to-demand organization, cost per unit is still going a major metric for evaluation, but a broader range of economic information reflecting the supply chain environment will be included. The cost metric will consist of inventory, warehousing, transportation costs, and disposal costs for excess and obsolete inventory. New metrics will also have to be employed to measure and track inventory materials at the suppliers, materials at plants, WIP, finished goods in plants, and finished goods in distribution centers.

In summary, it is not that a firm has to move completely to the theoretical just-in-time goal of production on demand, but rather the strategy should be to move a firm as close to this ideal as possible. The closer a firm is to one to one (that is, one unit demanded and one unit produced and delivered), the less waste in the supply chains. Some of the world’s greatest researchers on goal setting have found the best organizational results are achieved by goals that have been spelled out exactly in terms of what needs to be accomplished and where the bar has been set for high achievement (Johnson, 2012).

7.3.7. An Academic Perspective on Alignment

Noted scholars have offered suggestions on supply chain resource alignment strategies. Lee (2011, pp. 1–19) has suggested that in situations where the supply chain has become unaligned with customer demand managers should not try to tweak the supply chain but instead rethink it from end to end. The newer core issues on which the realigned supply chain foundation will be constructed, like sustainability, needs to be incorporated into the foundation, rather than just added on.

Where do you begin with such a Herculean effort? Slone (2011, pp. 195–214) suggests an alignment or realignment strategy. Basically, begin with the customer and work backward through the supply chain. Start with the customers’ current needs for the product, delivery, and price. Benchmark where it is possible to ensure competitive competence in the market place for the desired customers. Move backward through distribution channels to manufacturing and through the multiple tiers of suppliers, taking into consideration information technology, processes, management roles, and talents. Finally, make new partners as needed to meet the new customer demand.

Strategies like this sound simple, but are very challenging to implement. The lessons here are important guides in any alignment undertaking. Simply put, do not waste time making small changes to supply chains. Retool them completely and focus on the customer.

7.4. Other Alignment Topics

7.4.1. Strategy for Dealing with Explosive Growth During Introduction and Growth Stages of Product Life Cycle

Some firms are able to put an enormous amount of products before consumers during the Introduction and Growth Stages of the product life cycle. During these stages, a product is essentially alone in its market before other companies have a chance to introduce competitive products. Profit margins can be considerable during these life cycle stages, but once competitors enter the market, competition drives down prices and profit. One firm, Apple Computers, has found it could afford to spend more on manufacturing and distribution to get more product into the pipeline during these all-important early and exclusive high-margin stages (Turbide, 2011). One strategy is to build extra supply chain capacity in to the current system in anticipation of a spike of demand growth. For example, a firm can contract for a great deal of air cargo space in anticipation of a new product’s initial release. While air transportation is more expensive, shipping time may be reduced to a day rather than take weeks for slower transportation modes (for example, shipping cargo) costing firms profit. Slower modes are simply untenable in fast-changing markets. Apple also buys manufacturing capacity and locks up supplies of certain components and materials that may have limited availability. This strategy has the added advantage of reducing supplies of these components for competitors, delaying competitors’ efforts to bring competing products to market.

7.4.2. Dealing with a Logistics in Seasonal Growth Surge

Express freight carriers, who are major partners in many firms’ supply chain, have to deal with seasonal or holiday growth surges from customers. How a firm like FedEx handles volatility in service demand can be applicable to any firm having to align its supply chain resources to deal with excessive growth in customer demand.

FedEx projected the company would have to ship more than 260 million packages between Thanksgiving and Christmas in 2011, which represents a 12% increase from 2010 (Strategic Sourceror, 2011). FedEx’s worldwide shipping hub at the Los Angeles International Airport employs hundreds to handle and process packages on miles of conveyor belts. Moving the packages from the airport to a sorting warehouse, the latest in material handling technology is employed. To ensure packages are not misplaced, FedEx invests heavily in advanced technological monitoring devices. These systems help FedEx not only to track boxes but also to measure them. This enables the company to leave no space unused when loading packages on planes and trucks. Even with that capital investment, substantial growth surges can overwhelm the normal staff capacity. To deal with the growth in demand, FedEx augments its strategy of increasing staffing capacity by employing an additional 20, employees. To process the millions of boxes, FedEx separates these employees into groups tasked with individual duties. For example, some employees work specifically to investigate where packages containing no address labels should be directed, while others unload planes and trucks.

Utilizing specialization of labor, materials handling technology to improve efficiency in shipping, and a temporary increase in staffing are all useful approaches for dealing with rapid growth surges.

7.4.3. Contingency Planning as a Growth Strategy

Aligning physical facilities for future growth in products or for an entire supply chain is prudent contingency planning. Knowing that growth will eventually occur, it is prudent to be prepared with sufficient supply chain capacity. An example of a firm that undertook a major change in distribution centers in 2011 is illustrated by Skechers USA, a major footwear company.

The company started with five leased distribution centers in Southern California representing 1.7 million square feet of facilities. Each of those facilities had different equipment, and each handled a different piece of the order fulfillment process. Regardless, the facilities resulted in higher costs due to the additional handling required to move a product between facilities for order fulfillment processes. The product was received from the ports in one building, picked and packed in another, and potentially picked up in a third. A great deal of effort was spent constantly shipping products from one building to the next until they arrived at the appropriate locations. Skechers wanted to consolidate operations under one roof, but it also wanted to maintain a central point for North American distribution rather than develop a distribution network. Having regional distribution centers resulted in having inventory on the East Coast that was needed on the West Coast and vice versa.

With the idea of product growth in mind, they designed a single facility of 1.82 million square feet located about 80 miles west of the port in Long Beach, California, where Skechers imports all of its footwear and athletic gear. The facility seeks to meet two important strategic goals: consolidate operations, and set the stage for continued growth. The new distribution center is one that is highly automated and able to handle all the footwear company’s North American distribution. The new distribution center consists of three distinct areas for work, each measuring about 600, square feet. Two areas are devoted to receiving with about 400, square feet of reserve storage in each; the space in the middle is dedicated to order fulfillment and shipping.

The new facility is one of the largest distribution centers in California and was designed to be one of the most efficient. The facility has an automated materials handling system that minimizes the number of times a pair of shoes is handled between receiving and shipping and is capable of managing an inventory of 70, stock keeping units (SKUs) and processing approximately 17, pairs of shoes per hour. The improvement in performance to meet growth goals is more than double the 7, pairs per hour handled in the former five leased distribution centers, and it is doing so with less than half the number of employees previously required. The facility and its automation systems are designed for flexibility. For example, both automated storage/retrieval systems (AS/RS) units are expandable. Thinking well ahead, Skechers also purchased an adjacent lot big enough for another facility should it outgrow this new one.

7.5. What’s Next?

Social media (that is, Web-based or mobile technologies used to generate communications with interactive dialogue among organizations and individuals, allowing creation and exchange of user-generated content) has been used in businesses primarily in marketing and human resources. Examples of social media platforms include Social-Flow and Attensity (both used for social media measurement) and Central Desktop and Creately (used for collaboration).

Casemore (2012) suggests social media will become increasingly important in all business operations, including supply chain management, and offers four areas of potential future benefits:

• Aid in creating knowledge networks: Using social media venues like Facebook and Twitter, a firm can rapidly capture and respond to customer feedback. Social media can then be used to obtain real-time feedback from the supply chain, both internally (inventory, warehousing, and procurement departments) and externally (suppliers and contractors). For example, a client firm with a materials or equipment need could have a network of suppliers watching its supply chain Facebook page. It can post the specs on what it needs, including pictures and video of the materials or equipment, with due dates for bids, and other relevant information. The suppliers and client firms can then use mobile technology to respond back and forth, leaving a trail of communications that constitute a complete record of the request, the supplier selection and performance, and any related issues.

• Speeding up the decision making process: The speed with which many social-media platforms can provide video, audio, and written communications across a vast network of suppliers in real time, will support agility and flexibility goals in supply chain decision making.

• Portable information: The increase in demand for information portability availability over mobile devices requires the ability to instantaneously access information. Social media is well positioned to offer the necessary platforms.

• Transforming collaboration with community: The need for transparency in supply chain business requires ever-closer relationships with key suppliers. Building a network community of suppliers, where critical information, opportunities, and ideas for improvement can be shared and implemented in real time, provides a competitive advantage for organizations. Also, engaging suppliers through social media is a useful way to stimulate supply chain innovation. Social media platforms are an ideal foundation for such communities.