Chapter 2

Board Cyber Risk Oversight: What Needs to Change?

Tim J. Leech, Risk Oversight Solutions Inc., Canada Lauren C. Hanlon, Risk Oversight Solutions Inc., Canada

The introduction to this book opens with a succinct statement from Tara to Tom, the CEO who has attempted to delegate accountability for responding to the board’s request for a cybersecurity road map to his chief information security officer. Tara told Tom: “No, you own cybersecurity; we oversee it alongside the board . . . I don’t mean our IT approach, I mean our whole-of-organization capability to manage cyber threats.” This type of clarity and direction to CEOs is relatively new, but one that is gaining traction globally.

From a pragmatic perspective, the key question well-intending boards need to be asking is “what specifically do we and the organization’s CEO need to do differently to meet these new cybersecurity expectations?” The problem they will immediately confront is a veritable ocean of advice on how to do this. This chapter focuses on the following three questions: (1) what are boards expected to do now?; (2) what barriers to action will well-intending boards face?; and (3) what practical steps should boards and organizations take now to respond? Be warned, however; the steps proposed in this paper are a radical departure from status quo thinking.

What Are Boards Expected to Do Now?

The first short answer is the frustrating and quite common “It depends.” It depends on what country your organization is in, the focus and approach of regulators in that country, the business sector the organization is in, the evolution of legal duty of care, the frequency of major governance crises linked to cybersecurity breaches, the culture of the organization, and more.

For busy directors, new expectations and calls for change are often best received and embraced when the communication comes from other board members. In 2014 the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) in the United States recognized the emerging need for director guidance following a flurry of major scandals involving breaches of information technology (IT) security. The NACD produced a well-researched, readable, and succinct “Cyber Risk Oversight” guide. This report is available without charge by registering at https://www.nacdonline.org/cyber.

The NACD guidance distilled what the authors believe directors should do to five core principles:

- Directors need to understand and approach cybersecurity as an enterprise risk management (ERM) issue, not just an IT issue. (Authors’ note: This is the key principle.)

- Directors should understand the legal implications of cyber risks as they relate to their organization’s specific circumstances.

- Boards should have adequate access to cybersecurity expertise, and discussions about cyber risk management should be given regular and adequate time on the board meeting agenda.

- Directors should set the expectation that management will establish an enterprise-wide cyber risk management framework with adequate staffing and budget.

- Board-management discussion of cyber risk should include identification of which risks to avoid, accept, mitigate, or transfer through insurance, as well as specific plans associated with each approach.1

The board should define the risk appetite for the organization and approve the likelihood and impact scale at the enterprise level. The board may be involved in the insurance aspect, depending on the contract value and possibly the choice of the insurer. Then it is up to management to address the risks that are above the threshold.

For those directors willing to invest more time skilling up on cybersecurity, the U.S. government has produced the widely acclaimed “Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity” version 1.0.2 It is important to note that the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) IT security framework does not emphasize the key role of the board of directors. Unlike some other more silo-leaning IT security guides, the NIST framework does promote the need to see cybersecurity as a subset of ERM. It proposes a cybersecurity maturity framework linked to risk management and what NIST calls an “integrated risk management program.” Unfortunately, the NIST guidance doesn’t give much practical advice on how to transition IT security assessments from what is often a silo-based approach to one that is fully integrated with an effective enterprise risk management framework.

The Short Answer

A quick scan of global developments confirms that, although the specific answer to the question will evolve over time on a country-by-country and sector basis, the answer can be summarized simply as “a lot more.” However, the central message in this chapter is that it should not be “a lot more of the same,” referring to the siloed, specialist-driven approach in use in a large percentage of organizations today. Cyber risk management and assurance needs to be reengineered globally.

What Barriers to Action Will Well-Intending Boards Face?

Most boards will face difficulty as they attempt to address cyber risk management. The five main categories of barriers to action can be identified as follows:

- Lack of senior management ownership of IT security.

- Failure to link cybersecurity assessments to key organization objectives.

- Omission of cybersecurity from entity-level objectives and strategic plans.

- Too much focus on internal controls.

- Lack of reliable information on residual risk status.

These barriers are discussed in further detail in the following sections.

Barrier 1: Lack of Senior Management Ownership

In many organizations the perception is that IT security is the IT department’s and internal audit’s problem, not something the CEO and C-suite own. Senior management is ultimately responsible for all major threats to an organization, so it is critical that the C-suite takes ownership of this and assesses IT security in the context of key business objectives. IT security is often treated as a separate silo, with the majority of the work being done by IT, internal audit, and outside IT consultants that often lack “big picture” perspectives and experience.

This is compounded by a lack of clear line management ownership for assessing and reporting upwards on the state of residual risk linked to key value creation and value preservation objectives. All too often, ERM programs are relegated to an annual/semiannual update of the organization’s risk register and a collection of spot-in-time internal audits, not an ongoing process owned by management to continuously identify, assess, and treat key risks, including cyber risks, to important business objectives.

A key point that is often lost is that IT security should only be seen as important to the extent it significantly impacts the achievement of important business objectives that add significant value and/or preserve value for the organization. Because management in these organizations often do not have to formally assess, treat, and report upwards on risks that impact on the achievement of key organization objectives and related residual risk status, they do not actively participate in identifying cybersecurity-linked risks as part of a holistic enterprise-wide process. More importantly, boards are often not told which top value creation and potentially value eroding objectives are significantly threatened by low levels of cybersecurity risk treatments.

Barrier 2: Failure to Link Cybersecurity Assessments to Key Organization Objectives

A large percentage of boards are populated with pragmatic and very experienced executives who have learned to focus their scarce time and attention on objectives key to the success of the business. They are often quite attuned to the organization’s key objectives. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, a large percentage of the cybersecurity work done in many organizations is not directly tied to specific organization objectives. Boards are often not told which of the organization’s most important value creation and value preservation objectives are likely to be impacted by weak or nonexistent cybersecurity treatments and to what degree. In its most extreme form, the message communicated implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, by the IT security assessors is that having high levels of computer security should be seen as an objective in its own right. This premise can sometimes be promoted by well-intending regulators charged with raising IT security levels without specific cost-benefit analysis linked to the organization objectives impacted.

Senior management and boards have a difficult time deciding how much of the organization’s scarce resources should be dedicated to this area without high-quality information to assess which organization objectives are most likely to be impacted, and to what degree by low/nonexistent cybersecurity risk treatments. At the current time, based on Institute of Internal Audit (IIA) surveys globally, only a small percentage of internal audit, IT security, and ERM specialists link their risk and controls assessment work directly to the organization’s top, most important value creation and value preservation objectives.

Barrier 3: Omission of Cybersecurity from Entity-Level Objectives and Strategic Plans

In companies that have ERM functions, cybersecurity threats are often included in risk registers, which may or may not be directly linked to the organization’s top strategic plan and value-creation objectives. In order for cybersecurity to be robust and overarching, it must be included in objectives and strategic plans at the highest level of the organization. Many IT information security functions focus exclusively on IT security, often without directly linking how IT security impacts key organization objectives. Risk universes and audit universes that are developed by management, risk functions, or internal audit are often carved out as separate risk and audit topics and separated from the organization objectives the risks link to and potentially impact.

Barrier 4: Too Much Focus on Internal Controls

Too large a percentage of the ERM and internal audit work done today still focuses on identifying internal controls. Auditors make the primary decision in their audits and risk assessments if these cybersecurity internal controls are deficient or in need of improvement. The most extreme form of this is the binary approach imposed by Sarbanes-Oxley section 404. The groups doing this work often do not use processes aligned with ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management. This means that they do not assess risks in the context of specific, related organization objectives or deploy the full range of risk treatment options available, which are:

- Avoiding the activity that gives rise to the risk.

- Taking or increasing the risk in order to pursue an opportunity.

- Removing the risk source.

- Changing the likelihood.

- Changing the consequences.

- Sharing the risk with other parties (e.g., risk financing, contracts).

- Retaining the risk by informed decision.

Perhaps most importantly, when accepting some level of residual risk linked to key objectives, which is always the case, evaluate whether acceptance of the risk is appropriate in light of the organization’s and board’s risk appetite and tolerance.

Barrier 5: Lack of Reliable Information on Residual Risk Status

Higher-quality information is needed for senior management and boards to properly assess whether current levels of cybersecurity are appropriate and cost justified. The information should clearly answer the following questions:

- Which critical organization objective or objectives are impacted by cyber risks?

- How well are those objectives currently being achieved with the current risk treatment strategy?

- What are the potential impacts to reputation, cost, remuneration, and so on if an important business objective is not achieved in whole or part because of a cybersecurity risk realization?

- What viable risk treatments are available and could be used to reduce relevant cybersecurity risks, and at what cost, that are not being used?

- What information is available on current performance and risk indicators and any impediments management and the organization face?

What Practical Steps Should Boards Take Now to Respond?

There are four steps, outlined in this section, that boards can take to respond to risk. They are as follows:

- Use a “five lines of assurance” approach.

- Include top objectives and specific owners.

- Establish a risk management framework.

- Require regular reporting by the CEO.

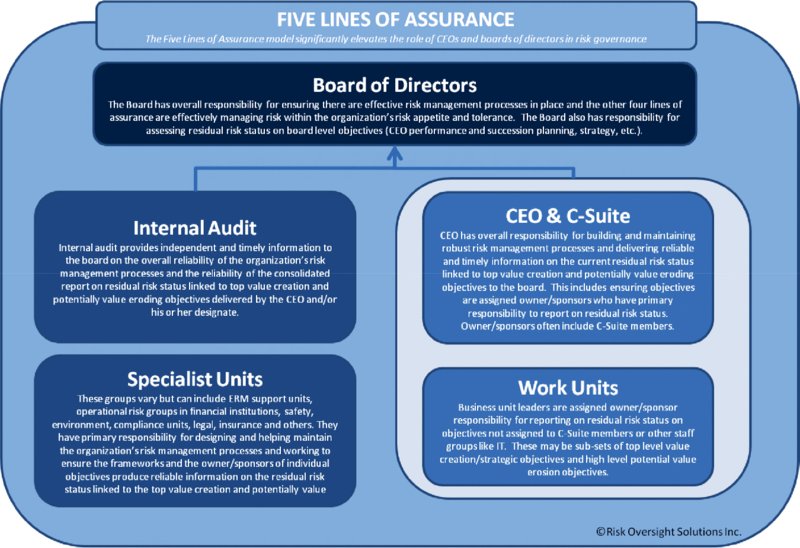

Practical Step 1: Use a “Five Lines of Assurance” Approach

The “five lines of assurance” approach to risk oversight and governance (Figure 2.1) models how an organization can operate effectively in the realm of cybersecurity. The five lines are, on one side, internal audit and specialist units; and on the other side, the C-suite and work units that report to them. All four of these lines provide information to the board of directors, the fifth line, and also directly execute and oversee risk-management programs.

Figure 2.1 Five lines of assurance

Cybersecurity deficiencies linked to the organization’s top value creation and value preservation objectives are often obfuscated and managed suboptimally. This will continue as long as:

- Senior management and work units are not expected to complete formal risk assessments on top value creation and preservation objectives and report upwards to the board on residual risk status.

- ERM groups build their work plans around “risk registers” with little direct linkage to organization’s value creation strategy.

- Internal audit departments continue to use “audit universes” as their primary work foundation and perform point-in-time direct report audits and form subjective opinions on “control effectiveness.”

It should be the CEO and C-Suite that decide which organization objectives warrant the cost of combined assurance overseen by the organization’s board of directors. The board and CEO should be seen as key players in a “five lines of assurance” approach—not mere recipients of reports. The CEO or his/her designate should be responsible for providing reliable consolidated reports on residual risk status linked to all top value creation and preservation objectives, including those that are being, or could be, impacted by cybersecurity threats. Boards need to oversee the overall effectiveness of the organization’s enterprise approach to risk management—including defining which objectives they want residual risk status information on and the level of risk assessment rigor.

Practical Step 2: Include Top Objectives and Specific Owners

For risk management to be effective, objectives registers must include the top value creation/preservation objectives and specify owners and sponsors at the highest organizational levels. These registers must clearly define risk assessment rigor and combined assurance levels. An organization’s ERM and combined assurance resources are costly. The C-suite should take the lead deciding which objectives warrant the cost of formal risk treatment, combined assurance work, and inclusion in the organization’s objectives register. The board should oversee that process. The objectives register should provide the foundation for the majority of formal risk treatment work done by management, risk specialists, and internal audit. Objectives included should be the objectives with the highest potential to increase entity value, as well as those with the highest potential to erode entity value. Cybersecurity risks are often relevant to both types of objectives. Each objective should have an owner/sponsor who has primary responsibility for assessing and reporting upward on residual risk status on a real-time basis.

Practical Step 3: Establish a Risk Management Framework

For risk assessment and treatment to be effective, it must be done using a framework focused on providing reliable information. Decision makers need to fully understand the composite residual risk status linked to top value creation and value preservation objectives. The framework should be designed to serve this purpose, and using it should be a requirement.

All risk assessment and treatment work should be done using an approach consistent with the ISO 31000:2009, Risk management—Principles and guidelines global standard, but more importantly, it should also put high importance on direct linkage of the risks assessed and treated to the relevant organization objective(s) and, most importantly, developing a reliable picture of residual risk status linked to top objectives for decision makers. Figure 2.2 describes key elements of the risk status approach.

Figure 2.2 Risk status approach to assessment and treatment

Owners/sponsors of each objective are required to complete risk assessments and treatments on those objectives with specified levels of risk assessment and treatments rigor defined by the C-suite and board and report a “Composite Residual Risk Rating” (CRRR) for each objective. In cases where the owner/sponsor believes no additional or stronger risk treatments are warranted but significant levels of residual risk are still being accepted by the organization, this needs to be communicated to the board, including cases where high levels of cybersecurity residual risk is being accepted.

Practical Step 4: Require Regular Reporting by the CEO

If, ultimately, the CEO is to be held accountable for cybersecurity, he or she must be fully aware of how the program is working. This can be accomplished by having the CEO deliver consolidated reports to the board on a regular basis. These reports should cover the residual risk status linked to the organization’s formal objectives. Internal audit should also report on the reliability of the CEO’s consolidated report.

Boards should be provided with reliable reports on the residual risk status linked to the organization’s top objectives on a regular basis, ideally quarterly. This should include a concise report on the objectives that currently have residual risk status outside of the organization’s risk appetite and tolerance, and what is being done about them, as well as areas where high levels of residual risk are being accepted by senior management. This report should put cybersecurity risks in the context of the end result organization objectives they relate.

Cybersecurity—The Way Forward

The way forward, if real progress is to be achieved, requires major changes in the way that a large percentage of organizations have historically approached risk governance generally, and cybersecurity in particular. Radical change rarely comes easily. Regulators, professional associations, boards of directors, senior management, internal auditors, and risk specialists must embrace the need for radical change in the area of enterprise risk governance and map out formal change management strategies. Cyber risks should not continue to be treated as yet another silo. Like many big undertakings, change needs to start with some small steps. Are you willing to advocate risk oversight and governance change at your organization?

Notes

About Risk Oversight Solutions Inc.

Risk Oversight Solutions is a boutique consulting and training firm based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and Sarasota, Florida, that helps clients who want more integrated and effective risk and assurance frameworks that cost less and deliver more. Figure 2.2 is trademarked as RiskStatusline™ approach to assessment and treatment. More information on what needs to happen for Board risk oversight can be found in the July 2015 article “Reinventing Internal Audit,” published in Internal Audit magazine, and the summer 2016 article Paradigm Paralysis in ERM and Internal Audit in Ethical Boardroom.

About Tim J. Leech, FCPA, CIA, CRMA, CFE

Tim has over 35 years of global experience in the areas of board risk oversight, ERM, internal audit, and forensic accounting fields, with a focus on helping public- and private-sector organizations with ERM and internal audit transformation initiatives. His April 2015 article “Reinventing Internal Audit” was awarded the 2016 Outstanding Contributor award by the Institute of Internal Auditors.

About Lauren C. Hanlon, CPA, CIA, CRMA, CFE

Lauren Hanlon has spent over 20 years providing insight on risk management, internal audit, and internal controls for public and private companies in various industries. She has provided innovative solutions and a fresh approach to ERM methodology and technology training for numerous organizations and risk specialists, including the Big 4 audit partners, in countries around the world.