Chapter 5

Cyber Strategic Performance Management

McKinsey & Company James M. Kaplan, Partner, McKinsey & Company, New York, USA Jim Boehm, Consultant, McKinsey & Company, Washington, USA

If you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it,” said George, the chief strategy officer, to a nodding CEO Tom.

Cybersecurity performance can be managed, but only if measured.

The ability to measure performance has always been at the heart of effective management, underlying decisions about how to allocate resources, which practices to employ and whom to reward. Much more so than in the past, this is an age of granular and systematic performance management. Senior executives are exploiting massive amounts of data to understand which products generate profits, which salespeople sell effectively, and which operational teams execute with the highest degree of efficiency.

Sadly, in many respects, cybersecurity is an outlier to this trend. Measuring cybersecurity performance is hard. Traditional business performance metrics like revenue or cost are not really relevant. Analogues to market risk and credit risk metrics like value at risk do not exist for cybersecurity. And measuring cybersecurity incidents might lead you to believe you are doing a good job protecting the organization—when in fact you are doing such a bad job monitoring the environment you cannot even detect ongoing attacks.

The difficulty in measuring cybersecurity performance does not make it any less important. The dynamic nature of the cybersecurity environment—with threats escalating rapidly, new technologies introduced constantly, and operational practices evolving quickly—makes it dangerous for cybersecurity executives to rely on experience and instinct in making decisions.

Fortunately, there is a better way. With enough creativity and true understanding of sources of value, cybersecurity elements worth managing can be measured (even if only by proxy). Measuring performance—and organizational health—is critical to catalyzing progress, instilling accountability, and ultimately achieving an organization’s strategic aspirations.

Pitfalls in Measuring Cybersecurity Performance

There are a number of pitfalls organizations should avoid in measuring cybersecurity, including:

- Irrelevant metrics. Many reports to the senior management team we see include some reference to the millions of attacks the organization faces per week or per day. While eye-catching, this number is entirely irrelevant. The overwhelming number of those attacks come from “script kiddies” that a minimally competent security capability can deflect with ease. For most organizations, the tiny percentage of attacks from sophisticated attackers represents the true risk.

- Focusing on lagging indicators to the exclusion of leading indicators. The frequency and severity of security incidents is important information but is inherently a lagging indicator—representing an output—rather than a lever or an input that a management team could choose to affect directly.

- Assuming more is better. Even those organizations that look at leading indicators (e.g., extent of encryption) can make the mistake of assuming more controls and tighter controls are always the right answer. Ten years ago, when environments were more likely to be wide open, this might have been the case. Today, organizations can very easily incur too much cost and create too much complexity by creating metrics that encourage the encryption of every piece of data and the application of two-factor authentication to every system when in many cases neither may be necessary.

- Relying on subjectivity. In a world where quantitative metrics are challenging, cybersecurity executives may be inclined to report that their data loss prevention (DLP) program or identity and action management (IAM) program is “red,” “yellow,” or “green.” Even if the team performing the color coding has the best intentions in terms of objectivity, subjective assessments like this one will always be less than credible with senior management in terms of driving decisions unless those colors are tied to specific measurable or milestone-driven targets.

- Measuring the cybersecurity organization rather than enterprise resilience. We are fond of saying 80 percent of what you have to do to be secure happens outside the chief information security officer’s (CISO) organization. The cybersecurity team cannot write secure code for developers or apply patches quickly for data center managers, even though both actions are critical to an organization’s overall security posture. As a result, it is easy to focus cybersecurity metrics on what the security team does directly, rather than what it is supposed to achieve by driving resiliency across the entire organization.

Cybersecurity Strategy Required to Measure Cybersecurity Performance

Organizations can measure cybersecurity performance only in the context of a cybersecurity strategy that tightly connects with an organization’s overall business strategy. Otherwise, they will stumble into one or more of the pitfalls described above.

At its core an effective cybersecurity strategy has four components: a business risk assessment, an enabling set of capabilities, a target state to get to, and a portfolio of initiatives.

Organization Risk Assessment

The underpinning of all cybersecurity strategy comes to us from Frederick the Great, who told his commanders, “Little minds try to defend everything at once, but sensible people look at the main point only; they parry the worst blows and stand a little hurt if thereby they avoid a greater one. If you try to hold everything, you hold nothing.” Perhaps if he had lived in the twenty-first century, he would have said that only ineffective CISOs try to protect all data to the same level.

Cybersecurity strategy starts with business and cybersecurity executives having a frank discussion about which data is most critical to the business, most attractive to attackers and therefore the most important to protect. Is customer data more sensitive than intellectual property or vice versa? What types of intellectual property (IP) are most important—pricing data or production plans? How does that vary by region or line of business?

Cybersecurity Capabilities

Once an organization understands its risks, it can start to determine what types of capabilities its needs to build to protect itself. Naturally, there are many frameworks organizations can select from. We like organizations to think how far they can progress in putting in place the seven hallmarks of digital resilience that we developed in conjunction with the World Economic Forum:

- Prioritize information assets based on business risks. Most organizations lack insight into what information assets need protecting and which are the highest priority. Cybersecurity teams must work with businesses leaders to understand business risks across the entire value chain and then prioritize the underlying information assets accordingly.

- Differentiate protection based on the importance of assets. Few organizations have any systematic way of aligning the level of protection they give information assets with the importance of those assets to the business. Putting in place differentiated controls (e.g., encryption or multifactor authentication) ensures that organizations are directing the most appropriate resources to protecting the information assets that matter most.

- Integrate cybersecurity into enterprise-wide risk management and governance processes. Cybersecurity is an enterprise risk and must be managed as such. The possibilities of a cyber attack must be integrated with other risk analyses and presented in relevant management and board discussions. Moreover, the implications of digital resilience should be integrated into the broad set of governance functions such as human resources, vendor management, and compliance.

- Enlist front-line personnel to protect the information assets they use. Users are often the biggest vulnerability an organization has—they click on links they should not, choose insecure passwords, and e-mail sensitive files to broad distribution lists. Organizations need to segment users based on the assets they need to access, and help each segment understand the business risks associated with their everyday actions.

- Integrate cybersecurity into the technology environment. Almost every part of the broader technology environment affects an organization’s ability to protect itself—from application development practices to policies for replacing outdated hardware. Organizations must lose a crude bolt-on security mentality and instead train their entire staff to incorporate it into technology projects from day one.

- Deploy active defenses to uncover attacks proactively. There is a massive amount of information available about potential attacks—both from external intelligence sources and from an organization’s own technology environment. Organizations will need to develop the capabilities to aggregate and analyze the most relevant information, and tune their defense systems accordingly.

- Test continuously to improve incident response across business functions. An inadequate response to a breach—not only by the technology team but also from marketing, public affairs, or customer service functions—can be as damaging as the breach itself. Organizations should run cross-functional “cyber-war games” to improve their ability to respond effectively in real time.1

It is easy to want the highest level of capability, but there are real constraints to consider. Achieving the hallmarks of digital resilience requires real organizational change across many business functions, so organizations have to ask what level of appetite exists for change. It also requires a level of skill in sophistication in the cybersecurity team that many organizations do not have and would have a hard time obtaining.

On the other hand, organizations also have to balance challenges like these against imperatives for change: How important is sensitive information to the future of the business? How sophisticated are attackers? What is the level of regulatory scrutiny? How important are cybersecurity capabilities and protections to customers?

Target State Protections

Once an organization has assessed its business risks and determined what types of capabilities it is going to develop, it can determine how it will protect its sensitive data. What information assets will be encrypted? How tightly should access to data be controlled? Do systems containing some times of information have to be hosted on a segregated, more secure network segment? Where will the organization push most rigorously for secure coding practices and patch management? How to do all this in a way that does not create confusion and complexity?

Organizations have to create tiers of protection that span many types of controls and protection and develop clear, criteria-based standards for what types of data get what tier of protection (e.g., all pricing strategies for high-margin businesses require tier-3 protection, which implies encryption at rest and two-factor authentication).

Given the wide variety of data assets that many organizations have, they will have to determine the target state of protections on a business line-by-business line basis.

Portfolio of Initiatives

Almost any effective cybersecurity strategy will imply significant business, technology and organizational change. As with any other strategy, these changes will, require a portfolio of initiatives. Each initiative should imply substantial change in a given area (e.g., secure coding, network security, identity and access management)—and should include a description of the future state aspiration, required funding, required management support, required skills, key milestones, and timing.

Some of the initiatives may be enabling in nature—they will reshape or enhance the organization. Many cybersecurity functions we know of are seeking to expand their use of managed services—not so much to reduce cost as to free up capacity to focus on higher order and more value added activities. Therefore, these organizations have initiatives to go-to-market for services like L1 security monitoring, vulnerability scanning or penetration testing. Many organizations also have initiatives to enhance the talent level of the cybersecurity team through a combination of external hiring and training. We believe training members of the cybersecurity team in relevant business issues, general problem solving, financial management, and executive communications can be especially powerful. Some of the initiatives will likely address governance by creating the structures and mechanisms to involve required business leaders in cybersecurity decision making and ensure alignment between the cybersecurity program and business strategy over time.

Creating an Effective Cybersecurity Performance Management System

To effectively manage the success of its cybersecurity strategy, organizations should put in place a cybersecurity performance management system. This system should have at least three components: measuring progress against initiatives, measuring capability, and measuring protection.

Measuring Progress against Initiatives

Necessarily, to get anything done, organizations need to decompose their cybersecurity strategy into a series of initiatives. Each of those initiatives should have a simple range of metrics decked against it: percentage of applications remediated, reduction in click-through rates on phishing tests, and so on; the exact metric will depend on the initiative in question.

Each initiative should have a least one metric that is indicative of medium-term (i.e., within a two- to three-year window) success, including the following:

- Data loss prevention (DLP) system(s) have decreased incidents related to inadvertent information release to fewer than 100 per annum.

- We will achieve 90 percent patch currency rates on all external-facing operating and network system components within two calendar years.

- One hundred percent of all software projects include security-enhancing components like continuous build and security component-related sprints within the first 10 percent of the project’s anticipated development life cycle.

- We will stop more than 99 percent of all attacks detectable by our information security systems by the end of the next calendar year.

- For every high-priority attack, we will identify the attacker (or attacking entity) within one quarter.

- At least 80 percent of managers attend one advanced-level cyber awareness training session per annum.

- Workforce click-through rates on annual phishing attack tests is less than 30 percent.

These metrics can be supplemented with additional, interim markers that indicate whether the organization is making sufficient progress against its strategic cybersecurity initiatives. Simply, “markers” act as “milestones” for the organization.

For example, for the metric, “DLP system(s) have decreased incidents related to inadvertent information release to fewer than 100 per annum,” some example may be:

- There is a DLP system installed, and it is managed by a member/team within the organization.

- The DLP system has been “tuned” with rules to prevent inadvertent release of information.

- Accurate reporting is in place to measure the number of inadvertent releases of information due to DLP “misses.”

- Inadvertent information release is seen to be decreasing since the DLP system was tuned.

Done well, markers lay out the roadmap for each initiative sequentially, such that when the organization is at one marker it can clearly see the path to the next. The steps along the path from the marker it is presently at to the one it is moving towards further breaks down into the activities and actions that are ultimately compiled into the initiative team’s implementation work plan.

The path between each marker is made up of sequential activities, with each activity broken into a series of actions assigned to specific people or teams. Laying out actions in a Gantt-style work plan, grouped by activity and divided according to the boundaries of each marker, helps tracking, transparency, and identifying organizational, financial, technical, or other dependencies.

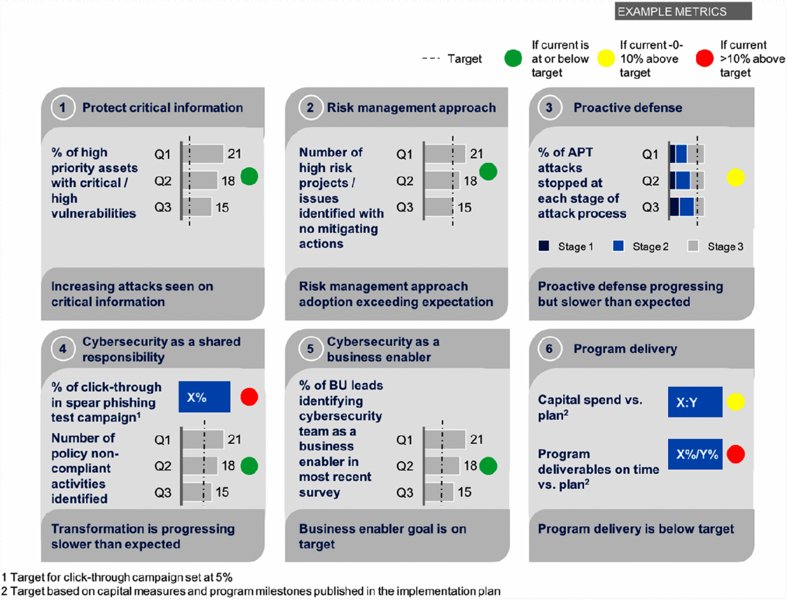

This is a relatively basic level of transparency, and it enables senior management to ensure the organization is making progress against the agreed-on cybersecurity strategy. It creates accountability for individual initiative leaders and can spur required discussions with various stakeholders about their level of engagement with and participation in critical initiatives. Figure 5.1 are example metrics for a six-step approach to measuring progress against initiatives.

Figure 5.1 Measuring progress against initiatives

Measuring Capability

In addition to measuring progress against initiatives, it is equally important to holistically measure an organization’s level of cybersecurity capability. There are a number of ways to do this, but we like to measure enterprise capability in terms of the seven hallmarks of digital resilience with our digital resilience assessment (DRA).

For each of the seven hallmarks described above, DRA measures performance against between 10 and 20 specific, tangible practices in how organizations capture risks or simulate the response to a potential breach. Any assessment of practices runs the risk of subjectivity, but DRA accounts for this in multiple ways:

- Structure of questions. DRA never asks “how good are you” at a certain practice; it asks “which of the following things do you do” and provides a scorecard for the respondent to compare current practices.

- Nature of respondents. In many cases, many people from a single organization will participate in DRA. This provides three benefits. First, it provides increased granularity—for example, incentives for developers to write secure code might be vastly different in two different business units. Second, it tends to average away respondents’ individual biases. Third, variations in responses tend to lead to very productive discussion about differences in assumptions and practices.

- Validation. Simply going through responses with each participant and asking why they responded as they did, tends to rebaseline or remove overly optimistic answers.

In the end, the DRA process provides an integrated, holistic, granular and actionable view of whether an organization has the capabilities to protect itself without creating undue cost and complexity for the organizations to manage. Figure 5.2 is an illustrative example of how DRA provides insight into cybersecurity capabilities.

Figure 5.2 DRA provides insight into cybersecurity capabilities

Measuring Protection

While measuring progress against strategic initiatives and measuring overall level of capability are incredibly valuable and relatively straightforward, neither directly answers the question, “are we protecting our most critical data?”

Doing that requires digging a level deeper and measuring the degrees of protection against an organization’s most important information assets:

- If an organization knows what its most important data is.

- And the organization knows what systems that data sits on.

- And the organization knows how those systems are currently protected.

- And the organization is aligned on how each type of data should be protected (e.g., level of encryption, two-factor authentication, etc.).

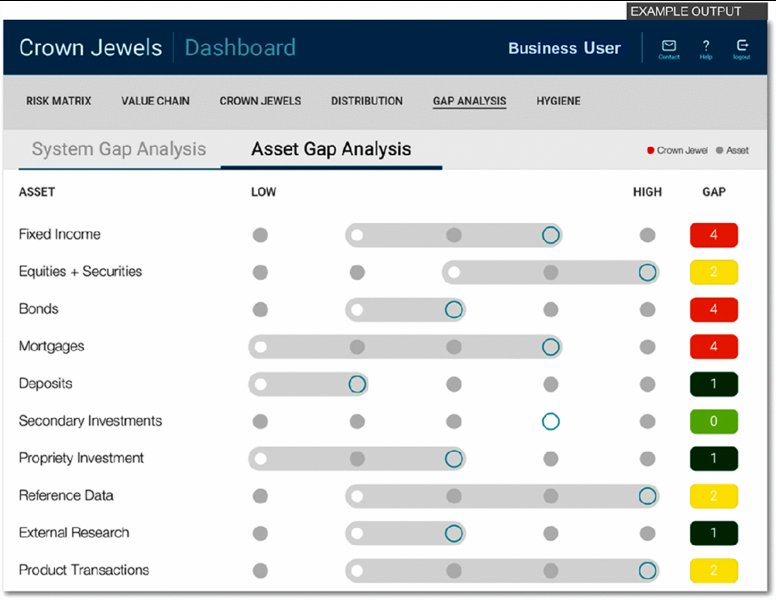

Figure 5.3 is an example output dashboard for the “crown jewels,” or how to measure the protection of the most critical information to the organization.

Figure 5.3 Measuring protection of most critical information Courtesy of John Greenwood of McKinsey & Co.

Then the organization can start to measure and report on whether it is protecting critical data sufficiently. The cybersecurity team can initiate discussions with senior management along the lines of:

- We have agreed, as a matter of policy, that customer information for our high net worth segment should be encrypted at rest, should require two-factor authentication and should require validation of access rights every 90 days.

- However, less than half of the systems hosting this type of information meet all of these commitments: Operations does the best with 70 percent of data protected to specification; Trading is in the middle with about 55 percent of data protected to spec. The real problem is in distribution, which protects only 25 percent of the spec.

- Within distribution the biggest problem is encryption—that drives 80 percent of the gap the specified commitments.

With this type of information the cybersecurity team and senior management can, if required, revisit whether the level of protection agreed on was realistic or needs to be adjusted. They can align on clear problem areas that need to be addressed, what the root cause of the issues might be, who is responsible and what actions to take to remediate the situation.

Conclusion

Like any other business function, effective management of cybersecurity strategy requires effective measurement. Certainly, for a number of structural reasons designing and implementing a good performance management system for cybersecurity is hard—but does not make it any less essential.

Fortunately, with appropriate management focus and attention, organizations can get effective mechanisms for managing cybersecurity in place. The key is to start with a practical strategy that addresses business risks, underlying capabilities, and target levels of protections with specific initiatives.

Once organizations do this, they can measure progress against those initiatives, assess the overall level of enterprise-level cybersecurity capability and understand the degree to which they are appropriately protecting their most critical data.

The following cyber risk management statement represents those organization capabilities CEO and board expect to be demonstrated in terms of a cyber risk strategic performance system.

Note

About McKinsey Company

McKinsey Company is a global management consulting firm that serves leading businesses, governments, nongovernmental organizations, and not-for-profits. McKinsey assists organizations in developing cybersecurity strategies that maximize business value and accelerate cybersecurity programs.

About James Kaplan

James is a partner with McKinsey & Co. in New York, New York, USA. James leads McKinsey’s capabilities in cybersecurity, which helps large organizations in implementing cyber-security strategies, conducting cyber-war games, optimizing enterprise infrastructure environments, and exploiting cloud technologies. He has published on a variety of technology topics in the McKinsey Quarterly, the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Harvard Business Review Blog Network. James is co-author of the book Beyond Cybersecurity: Protecting Your Digital Business (Wiley, 2015).

About Jim Boehm

Jim is a consultant with McKinsey & Co. in Washington, D.C., USA. Jim is a manager in McKinsey’s Cyber Solution and helps organizations design and deliver integrated cybersecurity strategies, implement bespoke cyber operations capabilities, assess digital resilience, and determine appropriate levels of enterprise protection. Prior to McKinsey, Jim was a U.S. Navy officer and national security program manager focusing on Agile development of cyber-analysis software and computer network operations.