Chapter 14

External Context and Supply Chain

Supply Chain Risk Leadership Council (SCRLC) Nick Wildgoose, Board Member and ex-Chairperson of SCRLC, and Zurich Insurance Group, UK

CEO Tom looked at his head of procurement/supply chain and operations, Ronald, and asked, “I hadn’t thought to take the external context—the supply chain—into account when looking at cyber risk management. Why should we?”

The reply was quick. “The first point is that in an increasingly specialized world where globalized outsourcing has been growing for a number of years, the percentage of an operation’s costs that sits in their supply chain is typically between 60 and 80 percent of the total costs.” Ronald explained that means that when things go wrong in the supply chain, they can have a dramatic impact on the overall organizational performance. Their globalized nature also means that there are many more opportunities for cyber risk to impact results.

He cited a few statistics from World Economic Forum’s “Global Risks Report 2016,” which finds risks on the rise in 2016. This, in turn, will be exacerbated by the coming fourth Industrial Revolution. A few facts struck Tom as particularly noteworthy: Evidence is mounting that interconnections between risks are becoming stronger and that these often have major and unpredictable impacts. Cyber attacks are now considered the greatest risk of doing business in North America. They also feature as a top business risk in no fewer than seven other countries, including Japan, Germany, Switzerland, and Singapore. This means that for an organization to be successful, it is imperative to ensure that critical supply chains are adequately protected against cyber threats.

External Context

Enterprise-wide risk management (ERM) requires that the external context unique to the organization is understood and established. According to ISO 31000:2009, Risk management—Principles and guidelines, the process outlines how those ERM parameters and variables, which externally control and influence how the organization achieves its objectives and manages its own set of unique risks. These include specifics for the scope of risk (what risks are inclusions/exclusions/relevant for an organization), risk criteria, and risk policy. External factors include PESTLE (political, economic, societal, technological, legal, and environmental) external factors, and others cited by ISO 31000:

- External stakeholder identification and analysis

- Operating environment

- Competitors

- Government policy

- Community expectations

- Commercial and legal relationships

- Public/professional/product liability

- Economic circumstances

- Natural and unnatural events

External Context Specific to Cyber Risks

The cyber and privacy risks associated with your customers, employees, partners, third-party service providers, and other outside forces must be carefully considered as external factors for the internal organization to manage. The era of hyper-Internet connectivity, the reliance on third-party vendors, and mobility creates a complicated matrix of cyber and privacy exposures and threats. Evaluating all these threats on an enterprise-wide basis effectively requires looking way beyond your network perimeter.

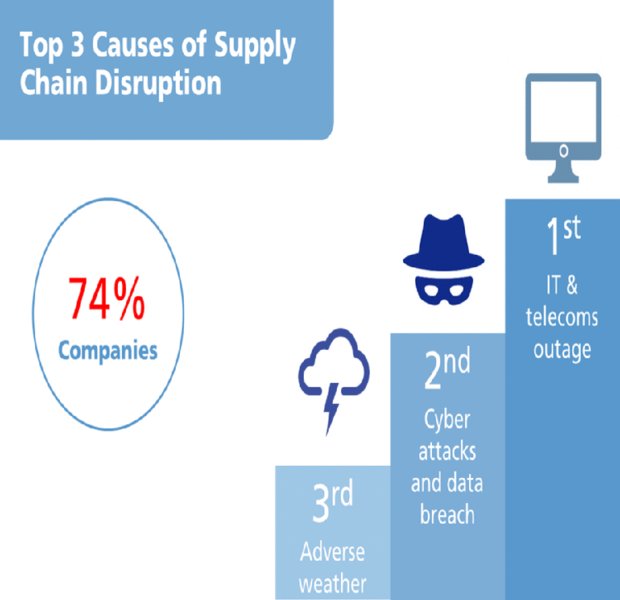

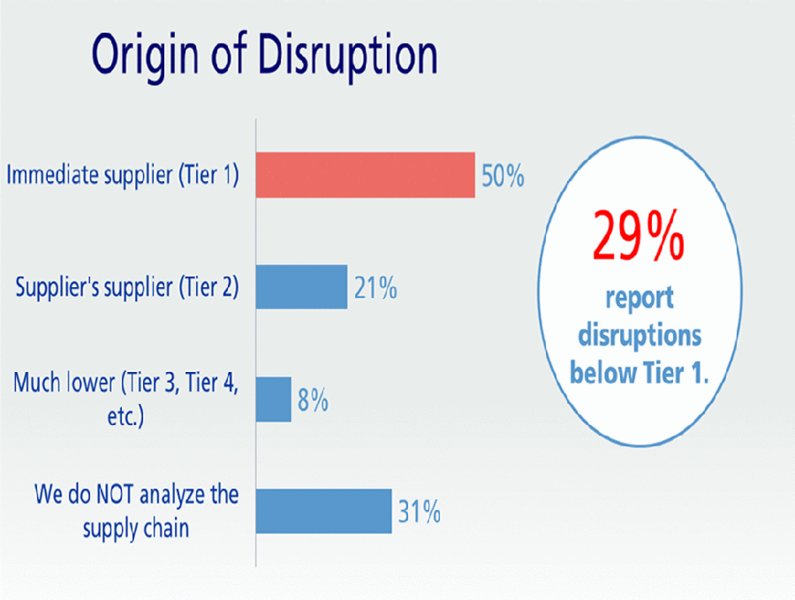

Cyber threats are now regarded as the second of the top three causes of supply chain disruption as in Figure 14.1 according to 74 percent of companies researched by Zurich in 2016. Of the sources for these disruptions, nearly one-third (29 percent) are not even sourced from first-tier suppliers but are “hidden” in third-tier suppliers, as seen in Figure 14.2. Disturbingly, 30 percent of responders report not analyzing their supply chain.

Figure 14.1 Top three causes of supply chain disruption

Figure 14.2 Origins of supply chain disruption

Major enterprises have experienced cyber breaches or business interruptions that have cost hundreds of millions and damage to the brand. While high-profile data breaches during 2014 and 2015 reflected the expanding spectrum of cyber threats, information security experts all agree that humans are the root causes of a majority of security incidents and data breaches. The interdependency in your critical global supply chains can have a multiplier effect. For example, a number of your critical suppliers all being affected by the same cyber incident.

External Context and the Supply Chain and Third Parties

As we already know, it is a challenge to be able to operate in your own organization on the matrix or cross-functional basis that is required in order to be able to optimize your cyber risk management practices. There is a further significant level of complexity when you look to interface with a third-party organization. This is because you have to ensure that each third party has the right approach in place to protect your data and to ensure they protect against disruptions to your own critical business processes. As with any interface, there are always opportunities for things to go wrong from a people, process, or systems perspective.

An initial assessment of the third party that you are dealing with can be gained by appropriate use of a cyber risk management maturity model within your third party due diligence. The extent that you need to validate this can in part be prioritized based on the following:

- Type and extent of access that the third party has to your data.

- Likelihood and impact of a potential third party failure due to a cyber attack on your operational performance.

- Potential reputational impact of the third-party cyber exposure.

An appropriate level of collaboration with the third party is essential to enable this to happen. It is important to realize that this type of relationship has a number of other benefits in terms of innovation or corporate social responsibility initiatives. All of these initiatives share the common requirement of a level of visibility into the processes and systems that are operating.

You also need to be aware in terms of your external context for your cyber risks that the legislative and regulatory requirements faced by your suppliers in the various parts of the world may be very different. These need to be factored into your overall cyber resilience plans.

However, the perceptions and cultures related to individuals operating in key decision-making areas of your external environment are equally important in a global context to the overall resilience that you are able to achieve. If key decision-making individuals in say, a critical supplier, do not have the same perception of the risks faced to your overall supply chain, then you will need to think about the appropriate alternative resilience and data security plans.

There are many examples of potential cyber exposures. Those that are illustrative from a supply chain perspective include:

- Smart cities with traffic control devices on the Internet of Things (IoT) that can be manipulated resulting in accidents, injury, and death or simply gridlock.

- Status of freight movement in trucks, ships, and aircraft is disrupted or manipulated resulting in damage to goods or early, late, or erroneous shipments or general supply chain turmoil impacting suppliers and purchases alike.

- Manipulation of signaling and the controlling the movement of trains.

- Manipulation of air traffic control or control of shipping port activity.

- Disruption of power delivery to critical transport infrastructure.

Transportation Sector Key Role for Supply Chain

The transportation sector plays a key role in the operation of supply chains. These include those in the pharmaceutical sector where lives are literally dependent on them. For many decades, logistics companies have invested most of their time and money into ensuring the integrity of their physical infrastructure and assets. Airlines and express operators have, for instance, been very mindful of the risks to their business of a terrorist infiltration of a bomb on board an aircraft or into a shipping container. However, less attention has been paid to the possibility of an attack on their information technology (IT) systems, which, depending on the source of the threat, could have consequences ranging from inconvenient to catastrophic.

Supply chains dependent on sea freight are perhaps uniquely exposed to cyber attacks. This is due to the way in which shipping has become increasingly channeled through the ever-decreasing number of ports capable of loading and off-loading the largest container ships. For example, a successful cyber attack on a port community system (a system responsible for the coordination of all port activities) of one the big “gateway” hubs, such as Rotterdam or Los Angeles, would have a substantial region-wide economic impact due to the lack of options available for rerouting of ships.

The logistics industry also faces threats, not so much to the control of transport assets, but to the goods themselves, which are being moved or stored. In terms of data, supply chain networks could be described as being inherently insecure, with parties encouraged to share information with their suppliers and their customers. The availability of data heightens the risk that the integrity or confidentiality of that shared information could be compromised. Supply chain management systems facilitate the dissemination of shipment-level information that, while enabling the efficient movement of goods, is also invaluable to criminals. The widespread use of handheld devices and Global Positioning System (GPS) technology in the field is only increasing the risks. Companies understand and manage this risk internally but have difficulty identifying and managing it across a large supplier base and this even includes just their critical suppliers.

The External Context to the Growing Importance of Cyber Risk and IT Failure

The Business Continuity Institute (BCI) has worked with the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS) and Zurich Insurance over a number of years to understand and survey the status of supply chain resilience. In the six years that the survey has been running, cyber as a cause of disruption has steadily increased reinforcing the importance of cyber resilience in an external context. The key findings from their 2015 report sourced from 537 respondents working in 14 Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) industry sectors (with the majority of these working for companies in excess of 250 employees based mainly in Europe or the United States) are set out below.

Building Cybersecurity Management Capabilities from an External Perspective

Seven Key Roles to Drive Capability from an External Perspective

The first key aspect of any cyber resilience and protection program in the context of the supply chain is to have the right organizational structure in place. There are a number of stakeholders to consider as you look at your cyber risk management strategy from an external perspective, the most important of which is that you have CEO/board-level sponsorship and support. There are seven key roles as summarized below.

- CEO/Board of directors. Accountable for overall business and organization performance, they have a fiduciary duty to assess and manage cyber risk. Regulators, including the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), have made clear they expect organization top leadership to be engaged on the issue. In order for your resilience imperative program to progress you need their support. They can also play a key role in coordinating with critical third parties at an executive-to-executive level.

- Chief financial officer (CFO). Concerns may range from the potential costs of a cyber event and what the impact could be on the bottom line as well as the reputational impact that such an event might have. They can also play a key role in coordination, building the business case and leading a cyber task force.

- Chief risk officer (CRO)/risk manager. Risk managers can ensure various stakeholders are connected in terms of assessing, managing, and responding to cyber threats. They can also provide access for key decision makers to leading practice methodologies, tools, and understanding.

- Legal/Compliance. As regulations around cyber develop, legal and compliance roles become increasingly important in keeping other stakeholders informed and engaged. And if a cyber incident occurs, lawsuits often follow.

- Procurement/Supply chain and operations. It is absolutely critical that cyber resilience is considered within the context overall supplier due diligence and management. This is often not adequately addressed and becomes even more important where critical data are being exchanged. It is also important that these functions maintain daily operations and workplace stability during a cyber event.

- Human resources/employees. Employees are often the weakest link in supply chain cybersecurity. Simple errors and accidents—or deliberate actions—by employees can lead to costly cyber incidents. Training on best practices is critical, especially with the rise in sophisticated “spear phishing” attacks targeting specific employees. Employees must be helped to understand the consequences of failure within a supply chain context.

- Customers/Suppliers/Logistic providers. Interactions with customers and suppliers can open you up to an attack. You need to understand the protections they have in place so they do not become the weak point in your cyber defenses.

Cybersecurity Task Force to Focus on Maturity Targets

Establishing a cybersecurity task force must be considered by every organization. Its charter is to take both an internal and external perspective when progressing the organization from the current state of its cybersecurity management system—and its supply chain subcomponents—to that targeted for the future.

The chief financial officer (CFO), with the coordination-support of the chief risk officer (CRO), should establish and lead this formal cross-functional task force. The task force aims to achieve the organization’s cybersecurity strategic objectives by reaching out to third parties and identifying the vulnerabilities in the supply chain within their organizations. Who is involved depends on the size and vulnerability of the organization, but appropriate representation from the seven functions mentioned above is required. It may also be appropriate to include key third parties such as outsourcing partners.

Avoiding Silos to Focus on External and Internal Alignment

Silo-biased organization functions create additional challenges for organizations trying to protect themselves from cyber attacks. Systematic preparedness is key; questions like what, when, how, and if need to be discussed and analyzed in a holistic manner rather than in silos.

You should have in place an organization that aligns the people, processes, and technology that encompass your cybersecurity response structure. You then need to make clear roles and responsibilities, including, for example, incident response and cyber crisis management plans with critical supply chain partners.

Integrating Supply Chain Capability from an External Perspective

Organizations will have maturity capabilities for cyber risk management to a greater or lesser degree. These will lie in identification, protection, detection, response, and recovery processes that operate in synchronization. The board will agree on risk acceptance/risk tolerance thresholds. Organizational readiness assessments can be used as a further method of understanding the cyber resilience status of the organization. Recovery scenarios will inform comprehensive recovery planning. Identifying and prioritizing organization resources helps to guide effective plans and realistic test scenarios. This preparation enables rapid recovery from incidents when they occur and helps to minimize the impact on the organization and its constituents (for example, National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST] Special Publication 800-184). However, organizations need to bolster their maturity capabilities for their cyber risk management system with components that more specifically address the supply chain and external factors perspective. These typically involve the following six factors:

- Understanding the risk. When looking at the business interruption exposure that might be caused by a critical supplier from a cyber disruption, it is key to understand the value at risk as well as the likelihood of disruption. You also need to understand cyber risk in the context of the data that your supplier is holding and the potential they might have to cause you reputational damage.

- Information sharing. It is key that information relevant to cybersecurity is shared appropriately across the internal silos. It is also important that relevant information is shared with critical third parties.

- Crisis communications. A documented, agreed, and tested communication plan needs be prepared based on a tailored set of cyber risk scenarios.

-

Training/exercising. As employees can be your weakest links, it is key that your own employees and those from key third parties adequately understand cyber risk processes.

War gaming as well as intrusion/penetration testing performed by hired profession hackers can be useful ways to test the robustness of these plans.

- Risk transfer tools such as insurance. These should be considered specifically in terms of third-party and supply chain exposure, where appropriate, in order to provide the relevant balance sheet protection. Insurance providers can also be a useful source of insights into cyber incidents based on their claims data.

- Leading practices and open standards. The use of the leading practices and standards covered in the other chapters of this book should be considered when assessing items from a third-party perspective and how much they have been embedded by critical third parties. It is also important that there is a level of interaction with relevant public bodies, as cyber risk needs to be tackled by a combination of both private and public action.

-

An example of how this might take place is set out based on work carried out by Zurich Insurance and ESADE. (See Table 14.1.)

- One recommendation arising from this work is for organizations to take targeted actions to mitigate cyber risk such as the mechanism of adopting the SANS 20 Critical Security Controls.

-

Table 14.1 Summary of Private-Sector and Policymaker Recommendations to Improve Global Cyber Governance

| Recommendation | Proposed Mechanism |

| Business | |

| Greater information sharing to mitigate cyber risk. | Insurance industry via the CRO forum. Anonymized business loss reporting via private-sector–led incentives (e.g., Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center [FS-ISAC]) and public-private bodies (e.g., European Union Agency for Network and Information Security [ENISA]). |

| Champion common values for global cyber governance in absence of governments’ consensus. | Lobby through institutions, particularly privately led initiatives (e.g., CRO forum and multi-stakeholder dialogue forums, such as the World Economic Forum). |

| Take targeted actions to manage cyber risk. | Adopt SANS 20 Critical Security Controls. Further actions needed for larger organizations. |

| Enhance general resilience to cyber risk. | Built-in redundancy, incident response, and business continuity planning, scenario planning, and exercises. |

| Policymaker | |

| Strengthen those aspects of global governance that have worked properly and isolate them from geopolitical tensions. | Develop informal global cyber networks. Adopt an if-you-build-it-they-will-come approach. |

| Create a system-wide institution for incident response. | G20+20 Cyber Stability Board. |

| Enhance crisis management to deal with a potential systemic cyber crisis. | Cyber WHO (World Health Organization). |

| Seek greater public-private cooperation. | Incentivize alignment of public-private interests on cybersecurity. |

| Reinforce protection of critical information infrastructures. | Cyber stress tests. |

Source: Zurich Insurance and ESADE Business School.

Measuring Cybersecurity Management Capabilities from an External Perspective

Supply Chain Risk Maturity Measured by Peer Organizations

The supply chain risk management system can be considered as a specialized child and subset of the parent overall ERM system. It shares a number of required organization capabilities with its “sibling,” that is, the cyber risk management system.

It is particularly important to reach a higher level of supply chain risk management system maturity given the speed and the significant consequences of cybersecurity threats. One way organizations with supply chain exposures can do this is to deploy the supply chain risk management (SCRM) maturity model designed by peer organizations that are members of the not-for-profit the Supply Chain Risk Leadership Council (SCRLC). This model is one methodology and a tool designed to help managers assess and measure their organization’s capabilities with respect to managing supply chain risk—which, of course, includes cyber risk. This model is freely available online as a gratis tool for self-assessment of SCRM capabilities.

Given the rising level of global cybersecurity threat, affected organizations should aim to reach a “proactive” maturity level as a minimum on the SCRLC maturity model. These are themed across five categories of capabilities (leadership, planning, implementation, evaluation, and improvement). The model produces three output charts that highlight the overall capability of an organization to manage supply chain risks and assessing the organization on a five-stage maturity rating scale (reactive up to aware, proactive, integrated, and resilient).

Conclusion

The following cyber risk management statement represents those organization capabilities the CEO and board expect to be demonstrated in terms of cyber risk external factors, especially the supply chain.

About The SCRLC

The Supply Chain Risk Leadership Council (SCRLC) is a not-for-profit body made up of global organizations sharing supply chain knowledge. The SCRLC web site offers a supply chain risk management maturity model as an easy-to-use spreadsheet model downloadable for free from http://www .scrlc.com/*. You may then use your own spreadsheet either retained in its original form as a specialized risk maturity model for supply chain, or adapt the maturity level attained on it as the rating to the cyber risk maturity model in the epilogue to The Cyber Risk Handbook. We thank the board at the Supply Chain Risk Leadership Council USA, who have kindly granted permission to any reader of this book to download and use their spreadsheet model.

About Nick Wildgoose, BA (Hons), FCA, FCIPS

Nick is a qualified accountant and supply chain professional and has held a variety of senior global financial, supply chain, and commercial positions in a number of industry sectors, working for companies such as PricewaterhouseCoopers, BOC Group, the Virgin Group, and currently Zurich Insurance Group. He has spoken and written on a number of topics related to value chain management. He served on the board of the Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply, which is the biggest professional body in the world. He has also served as a specialist advisor to the World Economic Forum on the topic of systemic supply chain risk and as chairman of the Supply Chain Risk Leadership Council, a select group of multinational companies looking to improve supply chain risk and still serves on the board. He is currently leading the rollout of innovative and award winning supply chain risk products for Zurich Insurance Group, which has given him the opportunity to interact with a large number of multinational companies and understand how they are addressing the real issues they are facing in terms of the globalization of their value chains and the threats they face from a cyber perspective.