Chapter 11

Monitoring and Review Using Key Risk Indicators (KRIs)

Ann Rodriguez, Managing Partner, Wability, Inc., USA

Tom is in a meeting with his chief risk officer, Nathan, and his chief information security officer (CISO), Maria. Maria is presenting on the progress of the information security program. Tom asks, “How do I know we are doing the right things? That our program is really where it needs to be? That we can really be ahead of this risk?” Nathan hands Tom a graphic one-page report. “Tom, here you can see what we are measuring to indicate risk levels associated with information security risk. These indicators, are already showing improvement given the current state of the program. As you know, ‘what gets measured, gets done’; so we are also tracking indicators associated with the program progress. These two sets of data provide a powerful story, which we can use to discuss with the board.”

Not many organizations have been known to fail due to a cybersecurity event. This is likely due to strong risk programs to detect and react to threats, and to luck. While no failures have been attributed to cybersecurity events, there are many operational losses that can be attributed to these events. With the velocity and sophistication of these threats constantly accelerating, it is imperative that organizations keep pace with how the risk is considered and the evolution of metrics to indicate potential changes in the risk levels.

The presentation and usage of key risk indicators (KRIs) sit at the pinnacle of strong enterprise-wide risk management (ERM). It routinely appears as an enterprise risk that organizations are concerned with as CEOs consider their strategic objectives and the implications that cyber events (and losses) can have on those objectives. In this chapter, we will discuss some design considerations for effective KRIs and their use—particularly for board and senior management.

Definitions

Many things are measured within an organization. We will loosely group this entire population of measured things and call them metrics or indicators. These metrics are ultimately clarified by their usage.

Key Risk Indicator

A key risk indicator (KRI) is a metric that permits a business to monitor changes in the level of risk in order to take action. KRIs highlight pressure points and can be effective leading indicators of emerging risks. These are typically forward-looking or leading indicators.1

Key Performance Indicator

A key performance indicator (KPI) is a metric that evaluates how a business is performing against objectives. A defined target (typically) provides the benchmark for evaluation of a KPI metric. These metrics are usually backward-looking or lagging indicators.

Key Control Indicator

A key control indicator (KCI) is a metric that evaluates the effectiveness level of a control (or set of controls) that have been implemented to reduce or mitigate a given risk exposure. A calibrated threshold or trigger (typically) brackets a KCI metric. These metrics are usually backward-looking or lagging indicators. Control indicators link with operational or process objectives.

If it is an important indicator, then it is considered key. Metrics may have multiple uses. They may inform performance, risk, or control. They are also layered for specific owners and accountable parties—building from control to process to objective, telling a story, and driving action and decisions at each discrete layer.

KRI Design for Cyber Risk Management

Every organization has a unique business strategy, risk appetite, and corporate culture. There is also a set of cyber risks that are independent of these factors that come with operating in the digital age. These include risks posed by web sites, e-mail, and digital devices, all of which can be hacked. As such, the specific cyber risks an organization faces will vary as will the program and associated KRIs. As with all KRIs, it is important to design KRIs that provide context to the broader enterprise risk. The layering of KRIs across the range of stakeholders that need information for them to action and govern is an important consideration.

A Risk Taxonomy Provides Clarity

A risk taxonomy is a comprehensive, common, and stable set of risk categories that is used within an organization.

- By providing a comprehensive set of risk categories, it encourages those involved in risk identification to consider all types of risks that could affect the organization’s objectives.

- By providing a common set of risk categories, it facilitates the aggregation of risks from across the organization.

By providing a stable set of risk categories, it facilitates comparative analysis of an organization’s risks over time.

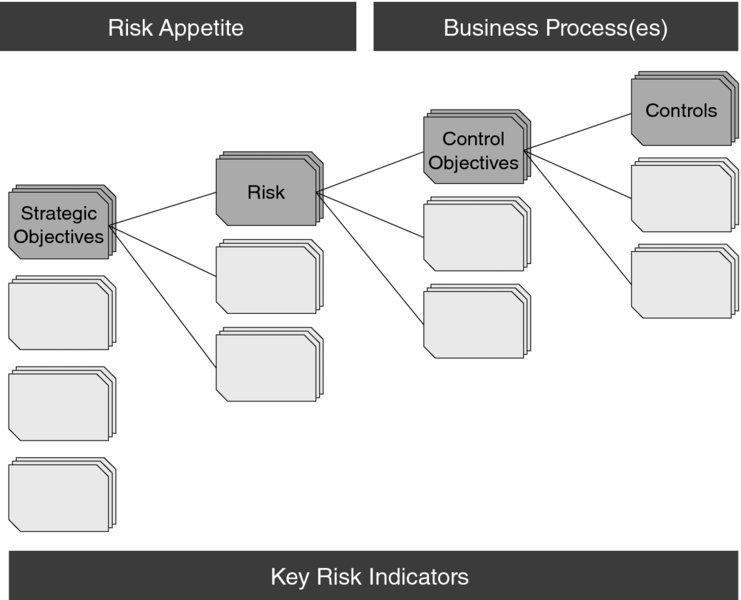

Having a risk taxonomy is critical when establishing a KRI program, which is critical for anticipating risk. It supports the relationship between metrics measuring control at a granular level with the risk they are mitigating and ultimately the relationship to strategic objectives as seen in Figure 11.1. The taxonomy also provides clarity of accountability and consistency of response and decision making within an organization across the range of stakeholders that use the KRIs.

Figure 11.1 Risk taxonomy for KRIs

Organizational Risk

High-level risk statements within the risk taxonomy represent how an organization might view the impact of a control failure within information security. These are essentially the things that could impact the profit and loss (P&L) by disrupting individual business processes and impacting customers. The following three are commonly viewed as risks to most organizations:

- Systems not available as expected.

- Information is exposed inappropriately (to those other than expected).

- Information is inaccurate and cannot be relied upon.

Organization leaders might not immediately care about the details of each control mitigating the various ways in which these risks could be realized; however, they do care about direct negative impact on their P&L and reputation.

Functional Risk

Cyber risk is a functional risk. This means that it is typically managed by the information security organizational function within information technology (IT). It spans the organization and requires clear integration with other functions apart from IT, such as vendor or supplier management, business continuity, and physical security, to name just a few.

Cyber risk as a functional risk type could have an impact on each of our preceding three business risks. Cybersecurity control objectives are aligned to these risks such that, if met, they would substantially reduce the risk. KRIs are designed and implemented to monitor changes in the cybersecurity risk level inherently and residually. These changes would then be reflected in the level of risk to the organization.

KRI Design Links Objectives, Risks, and Controls

KRI design begins with a clear view of the risks that the organization faces and continues with the further synthesis of these risks into control objectives and key controls (as in Figure 11.1). These elements of the risk taxonomy are manifest in the organization’s comprehensive cybersecurity program that start with policies and programs guided by industry best practices as well as applicable laws and regulations. The discrete programs form the basis for meeting control objectives which, when met, significantly mitigate the risk.

Organizational threats typically occur in the context of actors, targets, and vectors. We can illustrate how KRIs play a role in telling a story around risk, both inherently and residually, in the following way:

- Threat actor—a person or entity who impacts or has the potential to impact the security of an organization. These could be internal, external, or vendors/suppliers.

- Threat targets—the things we are trying to protect; things that are valuable to threat actors such as system working correctly, personal information, intellectual property, and so on.

- Threat vectors—paths that threat actors utilize to acquire threat targets; people (our employees, vendors, etc.) or systems or supply chain.

Table 11.1 indicates some examples of KRIs. These are aligned to high-level control objectives that are associated with threat vectors (because these are what we can control!) as well as threat actors. The KRIs are measured to provide an indication of the risk level and the strength of the program in consideration of our threat targets. In Table 11.1, KRIs that may need to be interpreted together are grouped in the column called “Examples of KRIs.” The multilayered approach to KRIs is also indicated in differentiating some examples of more detailed technical KRIs. Each of these KRI examples may also be separately categorized in one of four categories: incident counts, loss magnitude data, threat data, or control data.

Table 11.1 KRI Examples Aligned with Control Objectives

| Control Objectives | Examples of KRIs |

| Employees are trained and behaviors monitored. Culture and awareness efforts are distributed across the organization and monitoring is in place. Behavioral analysis is collecting events, looking at peer analysis, high-risk status, and employee activity and determining where risk hot spots are occurring. (Residual Risk) |

% Employee population trained % Employee population randomly tested % Successful test results % Employees with high risk score # Investigations that were legitimate % Investigations that were legitimate # Data loss events due to insiders Technical KRIs: Average amount of time between notification of job departure and elimination of corporate access Frequency with which employee access is reassessed % of employee access being reviewed when they change function within the enterprise |

| Know what is happening externally. Have a process to collect information quickly externally. (Inherent Risk) |

# Events across industry # New vulnerabilities detected Loss amounts across industry Peer maturity scores # Regulations applicable % Compliance to regulation |

| Know what is on the network. Have a complete and current inventory of production systems, IP addresses, devices, operating systems, etc.: their versions, physical locations, owners, function, and who has access. (Residual Risk) |

% Completeness of inventory (how much of network has been scanned) % Standardization of configurations across network % High-risk assets under regular access review Rate of compliance with the minimum security baseline Technical KRIs: % of employees with “super user” access # of properly configured SSL certificates amount of peer-to-peer file-sharing activity on a company’s corporate network # of open ports during a period of time % of third-party software that has been scanned for vulnerabilities prior to deployment |

| Swift risk assessment for vulnerabilities that affect our system. Have a complete and current inventory of existing security controls and configurations |

% of network security controls mapped % Systems with tested security controls % of high risk assets with weak or non–compliant passwords % High-risk data encrypted % Configuration standardization |

| and a mechanism for collecting vulnerabilities (real-time); speedy comparison of vulnerability with existing security controls to flag a vulnerability that could affect our system and a risk assessment process. (Residual Risk) |

Vulnerability scan score (considers frequency and automation percentage) Average incident detection time Trend of risk assessment timing (from when vulnerability collected) Technical KRIs: # Botnet infections per device over a period of time |

| Respond to vulnerabilities based on risk level such that business operations are not impacted. Have a response time that is based on the risk level and considers business operations. (Residual Risk) |

% Patch management program that is automated Trend of % patches causing business disruption Average incident response time Trend of speed of vulnerability response (from when vulnerability collected) # of unpatched known vulnerabilities |

| Ensure vendors are risk assessed and access is appropriate. All vendors are risk assessed based on their access to critical assets (i.e., threat targets) and their approach to fourth parties. (Residual Risk) |

% of vendors that are high risk (access to critical assets) % High-risk vendors with acceptable cybersecurity risk programs Frequency with which a company reviews its entire list of suppliers and vendors and designates those that are critical Frequency with which a company verifies its vendor’s controls % of critical vendors whose cybersecurity effectiveness is continuously monitored |

Case Study Where Triggered KRIs Were Apparently Ignored

The Target data breach in 2013 affected over 110 million customers and losses upwards of $250 million.

Hackers accessed the network using an HVAC (heating, ventilating, and air conditioning) supplier’s credentials. The HVAC supplier had access to the Target network, and used it to collect temperature and energy usage data from each store. The hackers were able to get the log-on credentials using a phishing e-mail aimed at Target suppliers. They deceived one of the HVAC employees who opened the e-mail, allowing them to infect some of the supplier’s computers. The hackers then waited until the malware captured the log-on credentials for Target. The HVAC vendor did not have adequate system protection, so the breach went undetected.

The Target event illustrates the need for cybersecurity integration in programs such as vendor or supplier management and to have a KRI program that governs response to KRIs.2

Using KRIs for Improved Decision Making

The objective of a strong KRI program is to improve decision making within the organization. Ideally, this should be forward looking. Reporting and presentation of the KRIs is both art and science. Much of the art in depicting the view of information security risk is in decoupling the detailed technical metrics and tech-speak, when presenting to senior leadership and board members. Another important consideration if presenting an abundance of KRIs is to avoid this leading to a false sense of security. Context and messaging are critical.

Stakeholders Want to Be Informed

There are a range of stakeholders in an organization that interact with the metrics measured to indicate changes in risk and control levels. The key stakeholders are typically the board of directors, senior management, chief risk officer, and chief information security officer (CISO) or head of cybersecurity. Differences as to how to present KRIs are directly related to the purview of the stakeholder group. The CISO or head of cybersecurity needs to have the most complete and granular set of KRIs to effectively manage progress and continuous improvement of information security.

Board members and senior management need to understand the inherent and residual risk associated with cybersecurity, as well as the cost of control. In order to understand these metrics, there needs to be a clear relationship of the cybersecurity risk to the organization strategy and to the organization risk appetite, as this is how the inherent risk would be viewed.

Here are the key things the CEO and the board of directors want to know about:

- Cyber risk culture and awareness.

- Inherent cyber risk (i.e., before controls are taken into account). Inherent risk level is usually influenced by changes in the threat level; new threat actors, uptick in attacks and sophistication, higher value of threat targets, and so on.

- Residual risk (i.e., after controls are taken into account). The level of control we have implemented over the various threat vectors that can be indicated by cyber program status, cyber program maturity, compliance, and peer comparison.

- Actual experience and trends: incidents, losses, policy violations.

- Big-picture metrics: the KRIs that illustrate support for the strategic objectives.

Inherent Risk, Residual Risk, and Big-Picture KRIs

There are several metrics that support inherent risk evaluation. Inherent risk arises any time a tool or process can result in potential losses. The aim of security controls is to mitigate inherent risks. This category of risk includes trend of exploits and vulnerabilities across the industry, trend of losses across the industry, and trends of losses that have occurred in companies with similar business models.

Residual risk is that which remains after security controls are implemented. Yes, residual risk is evaluated through metrics for a view of the scope, maturity, and integration of the information security program internally. The KRIs that are designed to indicate the strength of the information security program will be aggregate KRIs, such as percentage of employees trained, percentage of internal infrastructure covered, trend in incidents, response time to mitigate incidents, and trends in losses.

This view of inherent risk and residual risk that is overlaid onto strategic objectives and risk appetite helps an organization understand the cost of mitigation. Table 11.1 represents a useful way to overlay and link these components.

Aligning KRIs to the big picture—that is, the strategic objectives and risk appetite—is imperative for ensuring senior management understanding and support. The way to do this effectively is to align KRIs and design reporting so that the KRIs tell the story that relates to these business objectives.

For example, consider if one of your organization’s strategic objectives is to double revenue by expanding the customer base via an online channel. Each of the risks that could impact achievement of that objective must be evaluated and mitigated appropriately. It is quite easy to see that a risk scenario of an external direct denial of service (DDoS) attack would have an impact on customer experience by impacting system availability for customer’s transactions. This impact could result in lost revenue and customer retention. From this description, a few KRIs should be apparent, including customer satisfaction and customer retention. These can further be correlated with core system uptime, and the range of control metrics associated with protecting the network perimeter.

Dashboard Samples Tailored to Stakeholders

The cybersecurity and information security disciplines measure many things. They often deploy a robust set of dashboards and reports that are targeted and focused by each stakeholder.

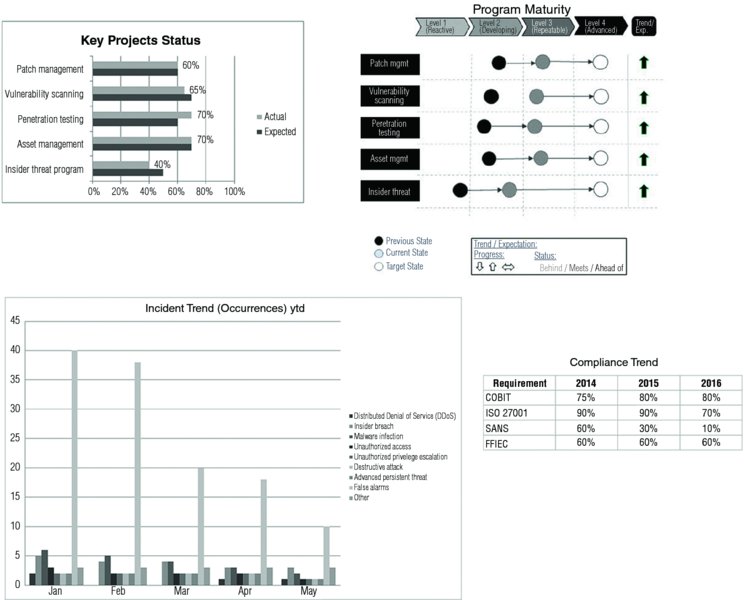

Figure 11.2 represents a sample high-level dashboard with some of the components listed above. These are all aggregated KRIs to provide some information about where the program is and how that relates to the actual experience. Remember that the objective of this reporting is to aid decision making, so these metrics may need to be adjusted to provide more tailored information. For example, the KRIs may be broken by business unit or geography.

Figure 11.2 KRI sample of dashboards and reports

Conclusion

There are many metrics associated with the control and outcomes associated with cyber risk management. The usage of these KRIs occurs at numerous levels in a company, from process and program owners, to the CISO and chief risk officer, and to the board and senior management. Effective design of KRIs and their alignment to the big picture will provide stronger engagement with the board and senior management in the company by providing them a not-too-technical look into the risk to achievement of objectives and the program that provides the control. The objective of effective KRI design is to try to be forward looking about the levels of risk and the related readiness to prevent or mitigate an event.

Notes

About Wability

Wability is a management and technical consulting firm that develops more efficient business strategies for Fortune 500 clients by creating and incorporating customized business and technological solutions. Wability focuses on providing the precise talents and skills and strategic advice needed to accomplish client objectives.

About Ann Rodriguez

Ann has significant experience across financial services in risk management including corporate governance and board reporting, enterprise and operational risk, with focus on technology, information security and third party risks. At GE Capital, Rodriguez established and provided leadership for both the Enterprise and Operational Risk programs. Leading a team of approximately 300 people across a $500 billion global company, she successfully integrated risk management with strategic planning, stress testing, capital planning, and comprehensive capital adequacy review. She established governance structures and provided leadership as chair of the New Products & Initiatives and Operational Risk Management Committees and as a member of the Enterprise Risk Management, Asset Quality, and Model Risk Committees. Rodriguez has held various leadership roles at Wells Fargo, Wachovia, and Goldman Sachs focused on risk governance and regulatory interface, operational risk management, and business management. Ann has an extensive background in consulting, as president of Wability, as lead partner over the Financial Services Consulting at BDO Seidman, and at Price Waterhouse, developing and leading practices in strategy, risk management, operational process excellence, and technology implementations. She has frequently shared her risk management experience, speaking at numerous industry conferences as well as lecturing at the NYU Stern School of Business. She is also author of the book Key Risk Indicators, a primer on the metrics required to provide proactive risk management.