Chapter 22

Access Control

PwC Sidriaan de Villiers, Partner—Africa Cybersecurity Practice, PwC South Africa

CEO Tom, addressing Maria, his chief information security officer (CISO), demanded, “In five words, tell me what is the most important thing to know about access control that is different when it comes to cybersecurity.”

Maria shot back, “Manual controls are simply ineffective.”

Taking a Fresh Look at Access Control

While the cybersecurity risk landscape has dramatically mutated, the approaches that organizations rely on to manage cyber risks have not kept pace. Traditional information security models do not address the realities of today. These models are still largely technology focused, compliance based, and perimeter-orientated, while aiming to secure the back office. IT security hygiene is often lacking, and ineffective access controls contributed directly to the half billion personal records lost or stolen in 2015. (See the foreword for more details.)

It is time to take a fresh look at access controls—to understand how going digital changes the fabric of your organization. This journey starts with the implementation and integration of the latest technologies, trends and platforms, including cloud computing, mobile technologies, and Big Data analytics, allowing stakeholders to interlink their social media environments on shared smart devices for personal and business usage. With the proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices and the expectation of being always connected, always online, consider the question: is our access control model still supporting our organization goals and addressing the right risks?

An effective cybersecurity program starts with a strategy and a foundation based on risks. According to PwC’s “Global State of Information Security Survey 2016,” 91 percent of the participants had adopted a risk-based cybersecurity framework. Although many organizations are using an amalgam of frameworks, the two most frequently implemented guidelines are the ISO 27001 and the cybersecurity framework of the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Risk-based frameworks can help organizations design systems, measure effectiveness, and monitor goals and risks for an improved cybersecurity program.1

Access control refers to the mechanisms and techniques used to ensure that access to assets is authorized and restricted based on organization and security requirements. The access control sections below, including the definitions given, are largely based on the ISO/IEC 27001:2013 (E) international standard, developed to provide requirements for establishing, implementing, maintaining and continually improving an information security management system (ISMS).2 Particular attention must be paid to the distinction between “can/may” and “should” and “must”. “Can” and “may” mean the following guidance can be considered as an option, whereas “should” is highly recommended, and “must” a necessity or requirement.

Organization Requirements for Access Control

The access control principles and activities covered below should be designed and formulated based on the organization and information security requirements for access control, with an overall aim of limiting access to information and information-processing facilities.

Based on a proper understanding of the organization, including its strategy, goals, and objectives, as well as the outcome of a risk assessment, the organization should formulate its access control policy with due consideration of the principles of need to know and need to use. The access control policy, including the sections discussed below, should be documented, approved, implemented, and reviewed based on the nature of the organization and its related security requirements. In determining the organization requirements, it is important to have a comprehensive understanding of your cyber threat landscape and your digital assets, including your company’s “crown jewels.” Many organizations have found that it is overly resource-intensive to implement maximum protection over all of their information components and information-processing facilities. The organization requirements for access controls should thus be crafted and modeled based on the specific nuances within the organization; they should support the overall organization goals, while protecting what matters most.

User Access Management

A large percentage of cybersecurity incidents stem from compromised login credentials. Attackers often follow the path of least resistance. They might search for the likes of unused user accounts (IDs), accounts with default passwords (the password set at installation and documented in the installation manuals), and accounts with easy-to-guess passwords. Therefore, to achieve the overall access controls objective, specific focus is required on user access management.

User Registration and Deregistration

The first step in providing access to a system is to create a user ID or user account; this process is also referred to as identity management. The process should apply to all types of users for all systems and services. User IDs should be unique to ensure accountability when access activities are logged and monitored. Therefore, sharing of user IDs should be prohibited, except where a process or device requires a user ID, for example, where an ID is required for a program that manages the backup function. This type of user ID is often a cyber attack entry target, so it is recommended that it be restricted to a physical device or that it is classified as a nondialogue user that cannot be used other than for the role for it was created.

Any request to register a new user should be approved by an organization or application owner or the reporting line manager. This applies to single sign-on integration, automation, workflow, or self-service solutions. At user ID creation, the user must acknowledge the conditions for access and adherence to relevant policies. The user ID or account should be created according to the documented naming convention. When a user resigns from the organization or when access is no longer required, the user ID should immediately be deregistered, removed, or locked on all systems. This will require effective integration with the organization’s human resource (HR) processes.

Manual user registration and deregistration has been replaced with workflow-based processes or advanced identity and access management (IAM) solutions. These IAM solutions have become a requirement in large multisystem environments, where thousands of identities and access rights are managed across geographical systems and organizational boundaries, including employees, contractors, customers, partners and vendors.3 For today’s complex requirements, organizations need intelligent IAM solutions.

User Access Provisioning

After the registration of a new user ID, a process called user provisioning—commonly referred to as entitlement management—is followed to allocate user rights and privileges to the user so they can access information or resources. The objective should be to design and allocate rights and privileges in such a way that user access is restricted according to “need to know” and “need to use” principles and the user’s role and purpose, meanwhile ensuring the segregation of duties (SOD). Role-based access control (RBAC) can be used to achieve this.

RBAC is an approach used to manage user rights and privileges (roles). It is intended to reduce the cost of security administration and ensure consistency of access principles. Permissions to perform certain system-based operations are assigned to specific roles, and roles are then allocated to users based on their function within the organization. As permissions are not assigned directly to users but only acquired through the assumption of roles, managing user rights is a matter of assigning predefined roles. Other access control approaches include mandatory access control (MAC), discretionary access control (DAC), rule-based access control (RAC), attribute-based access control (ABAC), history-based access control (HBAC), and identity-based and organization-based access control.4

A request for the allocation of rights and privileges to a user should be based on formal approval from the relevant organization or resource manager, in line with the agreed organization rules. An end-to-end trail of evidence should be retained of the user provisioning process followed for each request.

Management of Privileged Access Rights

The allocation of privileged (superuser) access to a user generally goes against the above overall access objective of ensuring restricted user access and the segregation of duties. User accounts with these roles are prime cyber attack targets and should be restricted, protected and controlled.

- It is sometimes necessary to give a superuser temporary access to fix errors, perform upgrades or deal with incidents—functions that cannot be carried out using normal support roles. In these exceptional instances, there are a number of controls that should be considered: Design and approve a superuser role to be used when required.

- Assign the superuser role or open the superuser ID based on special approval or a formal break-glass procedure requiring an incident to be reported in the incident management system.

- Send an automated alert to the security manager and organization manager when the role is activated or opened.

- Ensure that the activities performed by the superuser are logged (protected from manipulation) and promptly reviewed by the security manager and organization manager.

- Remove the role or lock the user ID as soon as the incident has been closed.

- It is strongly recommended that this procedure be automated or that tools are used in support thereof.

When an application user requires privileged access on an ongoing basis because of special circumstances, again the question must be asked: How is the risk managed? Special approval should be required, and the organization should design and implement adequate internal controls to mitigate the risk. A combination of the controls listed above should be considered.

New technologies are becoming available to assist with managing superuser access, from application-level to database-level access. Manual controls are simply ineffective.

Management of Secret Authentication Information of Users

The allocation and management of secret authentication information should be controlled through a formal process. The authentication information must remain secret at all times. This may be challenging if passwords or PINs are still being used as an authentication method, especially if supported by manual processes. Hackers may target stages of the authentication cycle through intensive organizational reconnaissance, social engineering, or other techniques.

When using a manual process to create user IDs or accounts, the user must be informed what the initial sign-on process is. Either the initial log-in will not require a password, or the initial password must be communicated to the user. The user is required to change the password within a specified time, and upon first log-in. Furthermore, when a user requires a password reset, it is critical that the identity of the user be validated before the password is reset. Communication is required between the function that will perform the reset and the user, including the new password. The user needs to log in with the reset password and then change the password within a period of time or upon next log-in so as to ensure secrecy.

It is clear from the preceding explanation that a manual process is open to attack. Hackers can intercept the passwords or use standard passwords applied by the organization during user creation and password reset. Technology should be considered to ensure the secrecy of authentication information, including one-time PINs (passwords) that are system generated and distributed via mobile phone, self-service password resets, integrated IAM solutions, and the like. Are passwords still an effective authentication method? Clearly not.

Review of User Access

Over time, a person’s role within the organization may change. For instance, user rights and privileges (allocated roles) might evolve as a result of promotions, transfers, terminations, or changes in responsibilities.

To ensure that access rights are still appropriate, access is restricted and the segregation of duties is in place, allocated user access should be formally reviewed at regular intervals. The frequency of reviews should be based on the risk classification of the systems or data involved. The application, resource, or system owner; line manager; or head of department concerned needs to review the list of users with their allocated access rights, following the documented process. The user access reviews can be integrated with modern governance risk and compliance (GRC) solutions, although it will still require manual activities.

For the review to be effective, the review group must be small enough and known to the reviewer, and the access information should be nontechnical to ensure that the reviewer can interpret the access he or she is responsible for. The reviewer should return the review results to the access maintenance group. Where it has not been confirmed that a user’s access has been reviewed, that user’s access should be suspended. This may seem drastic, but access control discipline is of crucial importance in the cyber world in which we operate.

As regards intelligent access management, this is an area where Big Data analytics on IAM data and log files in combination with access management intelligence could play a major role in the defense against cyber attacks. This will move us closer to “ongoing user certification,” reduce ineffective manual activities, and identify unusual behavior, while requiring human intervention only when exceptions have been flagged.5,6

Removal and Adjustment of User Rights

The human resources function should notify the access maintenance group of terminations to ensure that user IDs are immediately locked or deleted. This should preferably be automated so as to ensure the timely and effective termination of the user ID from all systems. The same controls described earlier should apply in the case of changes to access rights and privileges (user roles).

User Responsibility

The people component is often seen as the weakest link in the cyber chain. People are not equally diligent or knowledgeable when following processes or making decisions. As a result of leave arrangements, use of temporary staff, handover of responsibilities, and human emotional and physical well-being, manual controls are not consistently effective. Attackers will use social engineering, spoofing, phishing, brute-force attacks, and many other methods to obtain confidential information or to get a user to perform an activity that will compromise the organization.

Users must be trained in information security, and continuous awareness campaigns should remind them of cyber risks and the techniques used by hackers. Users must understand the importance of keeping their authentication information secret and their authentication devices secured at all times. Organizations should provide advice to users on how to select complex passwords and how to remember them, as writing them down will compromise the organization. Users must be aware of the access control policy, and they must understand the importance of full compliance and what their roles and responsibilities are in relation to information security.

System and Application Access Control

There are a number of fundamental requirements that need to be in place in order for an access control system to function at a basic level.

Information Access Restriction

Access to information and application systems must be restricted in accordance with the access control policy, on a need-to-know and need-to-use basis.

Secure Log-in Procedures

Access to systems and applications must be controlled by a secure log-in procedure that provides valid user identification, confirmed via effective authentication that is based on the risk profile of the information. Passwords are the most common way to authenticate as it is the simplest and most cost-effective authentication technique. But due to advanced hacking techniques and the exploitation of human behavior (ignorance and intentional or unintentional activities), we need more robust ways to protect valuable assets. As mentioned earlier, 91 percent of respondents to PwC’s latest Global State of Information Security Survey reported that they are already using advanced authentication for some forms of access.7

Organizations that use a risk-based approach should be able to classify data and users, and should implement higher levels of authentication or multilevel authentication for high-risk areas.

Advanced authentication can replace passwords or be used as part of multifactor authentication. This includes fingerprint identification, retina scanning, speech and type pattern recognition, confirmation via mobile devices, and security tokens. “In the near future, data analytics or adaptive authentication could make authentication easier and safer for consumers. The next big challenge for authentication will be the expansion of the ‘Internet of Things.’ Should this device be allowed to unlock my car or unlock my home?”8 Prepare for it.

Password Management System

Where passwords are used for authentication, the system must be interactive and ensure quality passwords. This includes enforcing the following conventions:

- Minimum length

- Prevention of historical passwords

- Regular changes

- Using special characters

- Using numeric values

- Mixed cases for alpha characters

- Avoidance of standard dictionary words, common passwords, or coherent phrases

Use of Privileged Utility Programs

Utility programs are often used to support the organization. However, any utility programs that are capable of overriding systems or bypassing controls should be restricted and tightly controlled. Due to the less restrictive access rights of utility programs, they are often targeted by hackers.

Access Control to Program Source Code

Access control to program source code should be restricted, as unauthorized access could result in exposure via backdoors, Trojan horse activities, and so on.

To protect the source code, consider deploying a combination of the following techniques to prevent malicious intent:

- Ring fence the source code storage area via segmentation or build an air-gap between the storage area and the Internet, as well as employees.

- Encrypt the source code.

- Implement very strict access controls to the source code areas.

- Perform peer code review to detect backdoors or other malicious code.

- Run software scans to find vulnerabilities.

- Electronically compare code.

- Automated system integrity checks to ensure the right code is in production.

- Strong automated version control.

- Automated code migration.

Mobile Devices

As mobile devices increasingly become part of our lives, and as businesses start to harden their on-site security, cybercriminals will focus more on mobile devices. Most organizations now allow corporate-issued or employee-owned mobile devices to connect to their networks and business applications. This is where the corporate/business and private worlds become interweaved. A user may now use the same device to read mails (business and private), open confidential attachments, make appointments, surf the Internet, make mobile payments, and use several social media applications, all while connected to an unsecured Wi-Fi network in a public location. Does this sound familiar?

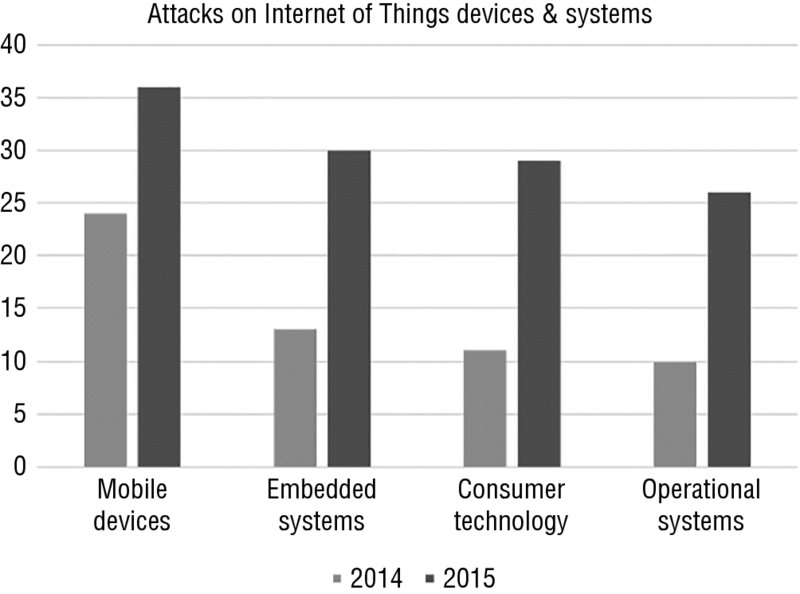

Risks associated with the use of mobile devices can include unauthorized access via unsecure Wi-Fi connections; loss or theft of data; mobile malware; phishing and spyware; the creation, use, or distribution of inappropriate content; organizational reputation; or simply having a confidential conversation over a cellular phone in a public place. Often, users store various log-in credentials on their mobile devices and if the device is compromised, then access to multiple business or private systems and applications is compromised. In this way, mobile devices can become an easy entry point for cybercriminals. Figure 22.1 shows how attacks on IoT devices have increased in percentage terms for 2015 over 2014, according to PwC’s “Global State of Information Security Survey 2016.”9

Figure 22.1 “The Global State of Information Security Survey 2016” .

Source: PwC, “The Global State of Information Security Survey 2016.” Content is reprinted with the kind permission of PwC

The modest mobile phone that was launched in the early 1990s has now become a sophisticated and powerful mobile computing device that is adding new levels of complexity to cybersecurity as it evolves ever further. Organizations can deal with mobile cyber threats by setting up mobile device management policies. This is no simple task. You have to navigate your way through a complex debate involving user expectations, productivity, and mobile freedom, and compare that to the mobile device risk to the organization. Ultimately, the benefits of mobility are in danger of being outweighed by the increase in your cyber risk.

Not all mobile devices offer the same security features. You therefore have to decide if you will allow all mobile brands and ranges of devices to connect to the organization’s network and applications. You can reduce your mobile cyber risk by using virtual private networks (VPNs), encrypting data (static and in motion), and having passwords on all devices. Through the central management of remote devices you can also locate a device, perform a remote lock or a data wipe, and enforce authentication—preferably multifactor authentication. You can also monitor device usage, and continuous feedback to the user community can change user behavior. Making users aware of mobility risk is therefore extremely important. Users should turn off all features and functions that they do not use, and all business systems and applications that are accessed by mobile devices should be secured via identity and device management, authentication, encryption, and privilege management. It is also a good idea to consider third-party solutions for antivirus, antispam, and intrusion detection. It is anticipated that native device software and third-party solutions will develop rapidly in this regard. (See Chapter 4 for more sample policy content for mobile devices and BYOD).

Teleworking

Teleworking or telecommuting is an arrangement where an employee uses computers and other telecommunication devices to work from a location other than the normal workplace, for instance, from home. This is often a temporary arrangement to assist an employee with their work–personal life balance or a particular set of circumstances, or where contractors or temporary staff are employed. While the human resource and potential cost benefits of allowing telecommuting are obvious, it does increase the cyber risk to an organization. The physical security within the telecommuter’s environment may not be as strong as at the workplace; people may share equipment or use unsecure communication and personal applications on it; and the hardware, software, and security arrangements in respect of the equipment and its configuration may not comply with corporate standards. It is also very difficult to detect noncompliance. The organization could consider a number of practices to reduce the related risk:

- Policy development. A clear policy is required to ensure that user behaviors, actions, and practices are acceptable. The roles, responsibilities, benefits, and conditions must be clear, and physical, logical, and paper-based security requirements must be well known.

- Use of equipment. If the organization provides the equipment, it has more control—it is easier to ensure that the equipment is configured and loaded with the same software and that the same protection is used as in the workplace. If staff are allowed to use their own computers, it is very difficult to achieve the same level of protection as in the workplace. The organization will have to be prescriptive about, for instance, the use of the equipment and licensed software, firewalls, and antivirus and spyware software.

- Encryption. Due to the physical access risk, all PCs and storage devices, including removable media, have to be encrypted to protect all stored data.

- Secure communication. All electronic communication with the workplace should be via a VPN, connected only to secure networks.

- Log-in. Adequate log-ins using proper identification and strong authentication controls are required.

- Support. Telecommuters should be provided with the necessary technical support.

- Training. Ongoing technical and cyber awareness training should be provided.

- Audits. Compliance audits should be performed as required.

- Access management. Those business systems and applications that are accessed by telecommuters should be secured using identity and device management, authentication, encryption, and privilege management.

Telecommuters should be treated the same as third parties that require access to your environment—provide them with a strong set of baseline standards, audit them, and treat all interactions with them cautiously.

Other Considerations

Cybercriminals are always on the lookout for crown jewels, those core digital assets that, if compromised, may seriously damage or even ruin your business. Valuable and confidential information, including your crown jewels, need protection.

Cryptography could be an effective way to protect your information. Consider the end-to-end process and ensure that information is always encrypted, whether stored (static) or in transit. Encryption can be used for a variety of applications, including hard drives, flash drives and other removable media, e-mails, critical Web transactions, and external communications.

Another aspect to consider is network security. General network controls include the implementation of procedures for network equipment identification and management; defining roles and responsibilities; strong authentication control (device and user authentication); the segregation of duties; firewalls and routers that are correctly configured; and, of course, encryption. It is also essential to focus on the logging and monitoring of network activity, including the use of advanced intrusion detection systems (IDSs). Despite these controls, however, there are no guarantees than attackers will not (eventually) gain access to your network. This is where network segmentation or zoning can protect your crown jewels. By zoning the network, you can limit the number of devices, users, and applications that operate in highly protected areas, thereby making it more difficult for attackers to access your more sensitive digital assets.

Conclusion

The following cyber risk management statement expresses those organizational capabilities that the CEO and board expect to be demonstrated in terms of access controls and cyber risk.

Notes

About PwC

With offices in 157 countries and more than 208,000 employees, we are among the leading professional services networks in the world. We help organizations and individuals create the value they’re looking for, by delivering quality in assurance, tax, and advisory services.

At PwC, we see cybersecurity and privacy differently. We don’t just protect organizational value; we create it—using cybersecurity and privacy as tools to transform organizations. By bringing together capabilities from across PwC, we seek to understand senior leaders’ perspectives on cybersecurity and privacy in the context of strategic priorities so they can play a central role in organizational strategy. By incorporating tactical knowledge gathered from decades of projects across industries, geographies, programs, and technologies, PwC can create and execute holistic start-to-finish plans.

About Sidriaan de Villiers, PwC Partner South Africa

Sidriaan started his career in IT, where he gained experience as a programmer, systems analyst, and project manager for retail applications and networking environments. He then joined PwC as an IT auditor in 1990 and started to specialize in ERP controls and security. Due to his ERP experience, he has been involved in a number of international engagements in countries that included Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, the Middle East, the United Kingdom, the United States, Switzerland, and Greece. With 30 years of experience in IT, computer auditing, risk management, data analytics, and system development life-cycle assessment, he is now responsible for the PwC Africa cybersecurity practice. He often lectures on controls- and security-related topics at colleges and universities in South Africa and is a regular cybersecurity presenter. More recently, he delivered a paper on controls and security in an ERP environment at the ORACLE Africa user group conference in Swaziland and was the keynote speaker at an ERP conference in Tel Aviv (Israel). Sidriaan holds BCom (Information Systems) and BSc (Hons Computer Science) degrees. As a member of ISACA, he completed the CISA certification in 1998, CISM in 2007, and CRISC in 2011.