PREPARING FOR YOUR USER REQUIREMENTS ACTIVITY

Introduction

Presumably you have completed all the research you can before involving your end users (refer to Chapter 2, Before You Choose an Activity, page 28) and you have now identified the user requirements activity necessary to answer some of your open questions. In this chapter, we detail the key elements of preparing for your activity. These steps are critical to ensuring that you collect the best data possible from the real users of your product. We cover everything that happens or that you should be aware of prior to collecting your data – from creating a proposal to recruiting your participants.

At the end of this chapter you will find a fascinating case study from Kaizor Innovation that focuses on international research studies. Specifically, the study details issues relating to using western research methods in China.

Creating a Proposal

A usability activity proposal is a roadmap for the activity you are about to undertake. It places a stake in the ground for everyone to work around. Proposals do not take long to write up but provide a great deal of value by getting everyone on the same page.

Why Create a Proposal?

As soon as you and the team decide to conduct a user requirements activity, you should write a proposal. A proposal benefits both you and the product team by forcing you to think about the activity in its entirety and determining what and who will be involved. You need to have a clear understanding of what will be involved from the very beginning, and you must convey this information to everyone who will have a role in the activity.

A proposal clearly outlines the activity that you will be conducting and the type of data that will be collected. In addition, it assigns responsibilities and sets a time schedule for the activity and all associated deliverables. This is important when preparing for an activity that depends on the participation of multiple people. You want to make sure everyone involved is clear about what they are responsible for and what their deadlines are. A proposal will help you do this. It acts as an informal contract. By specifying the activity that will be run, the users who will participate, and the data that will be collected, there are no surprises, assumptions, or misconceptions.

Sections of the Proposal

There are a number of key elements to include in your proposal. We recommend including the following sections.

History

The history section of the proposal is used to provide some introductory information about the product and to outline any usability activities that have been conducted in the past for this product. This information can be very useful to anyone who is new to the team.

Objectives, measures, and scope of the study

This section provides a brief description of the activity that you will be conducting, as well as its goals, and the specific data that will be collected. It is also a good idea to indicate the specific payoffs that will result from this activity. This information helps to set expectations about the type of data that you will and will not be collecting. Do not assume that everyone is on the same page.

Method

The method section details how you will execute the activity and how the data will be analyzed. Often, members of a product team have never been a part of the kind of activity that you plan to conduct. This section is also a good refresher for those who are familiar with the activity, but perhaps it has been a while since they have been involved in an activity of this particular type.

User profile

In this section, detail exactly who will be participating in the activity. It is essential to document this information to avoid any misunderstandings later on. You want to be as specific as possible. For example, don’t just say “students”; instead state exactly the type of student you are looking for. This might be:

It is critical that you bring in the correct user type for your activity. Work with the team to develop a detailed user profile (refer to Chapter 2, Before You Choose an Activity, “User Profile” section, page 43). When you write your proposal, it is possible that you may not have met with the team to determine this. If that is the case, be sure to indicate that you will be working with them to establish the key characteristics of the participants for the activity. Avoid including any “special users” that the team thinks would be “interesting” to include but are outside of the user profile.

Recruitment

In this section, describe how the participants will be recruited. Will you recruit them, or will the product team do this? Also, how will they be recruited? – Will you post a classified advertisement on the web, or use a recruitment agency? Will you contact current customers? In addition, how many people will you recruit?

You will need to provide answers to all of these questions in the recruitment section. If the screener for the activity has been created, you should attach this to the proposal as an appendix (see “Developing a Recruiting Screener”, page 161).

Incentives

In your proposal, specify how the participants will be compensated for their time and how much (see “Determining Participant Incentives”, page 159). Also, indicate who will be responsible for acquiring these incentives. If the product team is doing the recruiting, you want to be sure the team does not offer inappropriately high incentives to secure participation. (Refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, “Appropriate Incentives” section, page 100, for a discussion of appropriate incentive use.) If your budget is limited, you and the product team may need to be creative when identifying an appropriate incentive.

Responsibilities and proposed schedule

This is one of the most important pieces of your proposal – it is where you assign roles and responsibilities, as well as deliverable dates. Be as specific as possible in this section. Ideally, you want to have a specific person named for each deliverable. For example, do not just say that the product team is responsible for recruiting participants; instead, state that “John Brown from the product team” is responsible. The goal is for everyone to be able to read your proposal and understand exactly who is responsible for what.

The same applies to dates – be specific. You can always amend your dates if timing must be adjusted. It is also nice to indicate approximately how much time it will take to complete each deliverable. If someone has never before participated in one of these activities, he or she might assume that a deliverable takes more or less time than it really does. People most often underestimate the amount of time it takes to prepare for an activity. Sharing time estimates in your proposal can help people set their own deadlines.

Once the preparation for the activity is under way, you can use this chart to track the completion of the deliverables. You will be able to see at a glance what work is outstanding and who is causing the bottleneck.

Sample Proposal

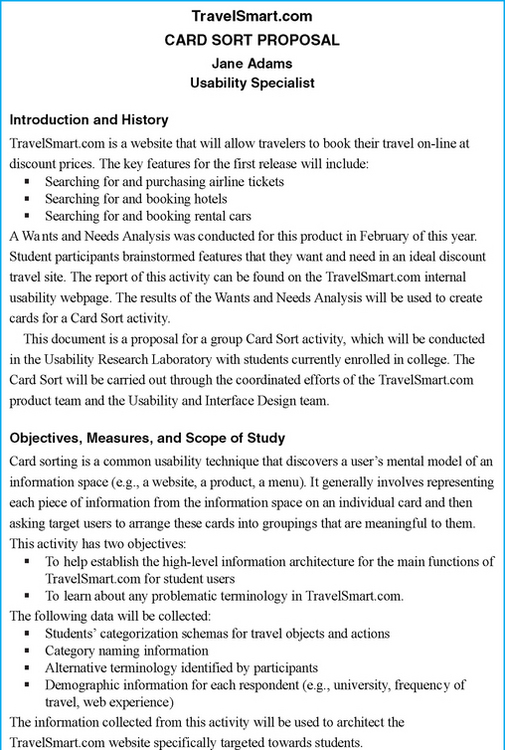

The best way to get a sense of what a proposal should contain and the level of detail is to look at an example. Figure 5.1 offers a sample proposal for a card sorting activity to be conducted for our fictitious travel website. This sample can be easily modified to meet the needs of any activity.

Getting Commitment

Your proposal is written, but you are not done yet. In our experience, if stakeholders are unhappy with the results of a study they will sometimes criticize one (or more) of the following:

![]() The skills/knowledge/objectivity of the person who conducted the activity

The skills/knowledge/objectivity of the person who conducted the activity

Being a member of the team and earning their respect (refer to Chapter 1, Introduction to User Requirements, “Preventing Resistance” section, page 18) will help with the first issue. Getting everyone to sign off on the proposal can help with the last two. Make sure that everyone is clear, before the activity, about all aspects of the study to avoid argument and debate when you are presenting the results. This is critical. If there are objections or problems with what you have proposed it is best to identify and deal with them now.

You might think that all you have to do is e-mail the proposal to the appropriate people. This is exactly what you do not want to do! Never e-mail your proposal to all the stakeholders and hope they read it. In most cases, your e-mail attachment will not even be opened. The reality is that everyone is very busy and most people do not have the time to read things that they do not believe to be critical. People may not believe your proposal is critical, but it is.

Instead, organize a meeting to review the proposal. It will likely take less than an hour. Anyone involved in the preparation for the activity or who will use the data should be present. At this meeting, you do not need to go through every single line of the proposal in detail, but you do want to hit several key points. They include:

![]() The objective of the activity. It is important to have a clear objective and to stick to it. Often in planning, developers will bring up issues that are out of the scope of the objective. Discussing it up front can keep the subsequent discussions focused.

The objective of the activity. It is important to have a clear objective and to stick to it. Often in planning, developers will bring up issues that are out of the scope of the objective. Discussing it up front can keep the subsequent discussions focused.

![]() The data you will be collecting. Make sure the team has a clear understanding of what they will be getting.

The data you will be collecting. Make sure the team has a clear understanding of what they will be getting.

![]() The users who will be participating. You really want to make this clear. Make sure everyone agrees that the user profile is correct. You do not want to be told after the activity has been conducted that the users “were not representative of the product’s true end users” – and hence the data you collected are useless. It may sound surprising, but this is not uncommon.

The users who will be participating. You really want to make this clear. Make sure everyone agrees that the user profile is correct. You do not want to be told after the activity has been conducted that the users “were not representative of the product’s true end users” – and hence the data you collected are useless. It may sound surprising, but this is not uncommon.

![]() Each person’s role and what he/she is responsible for. Ensure that everyone takes ownership of roles and responsibilities. Make sure they truly understand what they are responsible for and how the project scheduled will be impacted if delivery dates are not met.

Each person’s role and what he/she is responsible for. Ensure that everyone takes ownership of roles and responsibilities. Make sure they truly understand what they are responsible for and how the project scheduled will be impacted if delivery dates are not met.

![]() The time-line and dates for deliverables. Emphasize that it is critical for all dates to be met. In most cases, there is no opportunity for slipping.

The time-line and dates for deliverables. Emphasize that it is critical for all dates to be met. In most cases, there is no opportunity for slipping.

Although it may seem overkill to schedule yet another meeting, meeting in person has many advantages. First of all, it gets everyone involved, rather than creating an “us” versus “them” mentality (refer to Chapter 1, Introduction to User Requirements, “Preventing Resistance” section, page 18). You want everyone to feel like a team going into this activity. In addition, by meeting you can make sure that everyone is in agreement with what you have proposed. If they are not, you now have a chance to make any necessary adjustments and all stakeholders will be aware of the changes. At the end of the meeting, everyone should have a clear understanding of what has been proposed and be satisfied with the proposal. All misconceptions or assumptions should be removed. Essentially, your contract has been “signed.” You are off to a great start.

Deciding the Duration and Timing of Your Session

Of course, you will need to decide the duration and timing of your session(s) before you begin recruiting your participants. It may sound like a trivial topic, but the timing of your activity can determine the ease or difficulty of the recruiting process. For individual activities, we offer users a variety of times of day to participate, from early morning to around 8 pm. We try to be as flexible as possible and conform to the individual’s schedule and preference. This flexibility allows us to recruit more participants.

For group sessions it is a bit more challenging because you have to find one time to suit all participants. The participants we recruit typically have daytime jobs from 9 am to 5 pm, and not everyone can get time off in the middle of the day – so the time recommendations below focus on this type of user. Of course, optimal times will depend on the working hours of your user type. If you are trying to recruit users who work night shifts, these recommended times may not apply.

We have found that conducting group sessions in the periods 5-7 pm and 6-8 pm works best. We like to have our sessions end by 8 pm or 8:30 pm as we have found that, after this time, people get very tired and their productivity drops noticeably. Their motivation also drops because they just really want to get home. Also, a group activity can be quite tiring to moderate.

Because most people usually eat dinner around this time, we have discovered that providing dinner shortly before the session makes a huge difference. Participants appreciate the thought, and enjoy the free food; and their blood sugar is raised so they are thinking better and have more energy. As an added bonus, participants chat together over dinner right before the session and develop a rapport. This is valuable because you want people to be comfortable in sharing their thoughts and experiences with each other. The cost is minimal (about $60 for two large pizzas, soda, and cookies) and it is truly worth it. For individual activities that are conducted over lunch or dinnertime you may wish to do the same.

User requirements activities can be tiring for both the moderator and the participant. They demand a good deal of cognitive energy, discussion, and active listening to collect effective data. We have found that two hours is typically the maximum amount of time you want to keep participants for most user requirements activities. This is particularly the case if the participants are coming to your activity after they have already had a full day’s work. Even two hours is a long time, so you want to provide a break when you see participants are getting tired or restless. If you need more than two hours to collect data, it is often advisable to break the session into smaller chunks and run it over several days or evenings. For some activities, such as surveys, two hours is typically much more time than you can expect participants to provide. Keep your participants’ fatigue rate in mind when you decide how long your activity will be.

Recruiting Participants

Recruitment can be a time-consuming and costly activity if not done correctly. Below are some tips that should save you time, money, and effort. This information should also help you recruit users who better represent your true user population.

How Many Participants Do I Need?

This is one of the hardest questions to answer for any usability activity, and unfortunately there is no straightforward answer. In an ideal world, a user requirements activity should strive to represent the thoughts and ideas of the entire user population by involving every user. In a slightly more practical world, an activity would be conducted with a representative sample of that population, so that the results are highly predictive of those of the entire population. This type of sampling is done through precise and time-intensive sampling methods. In reality, this is typically done only in academic, medical, pharmaceutical, and government research (e.g., Census Bureau surveys), but not in typical product development activities. This book is focused on user requirements, so a detailed discussion of statistics is not appropriate. If statistical accuracy is essential for you, we suggest that you refer to a book devoted to statistics or research and design.

In the world of product development, convenience sampling is typically used. When employed, the sample of the population used reflects those who were available (or those you had access to), as opposed to selecting a truly representative sample of the population. Rather than selecting participants from the population at large, you recruit participants from a convenient subset of the population. For example, research done by college professors often uses college students for participants instead of representatives from the population at large.

Convenience sampling reflects the reality of product development. Typically, you need answers and you needed them yesterday. This means that you do not have the time or resources to get responses from hundreds of randomly selected users. So how many responses are enough? Because the appropriate sample size varies with each method, we will not explore a discussion of specific numbers in this section. In each method chapter, we suggest participant sample sizes based on our own practices and the practices of many usability professionals we consulted with while writing this book.

The unfortunate reality of convenience sampling is that you cannot be positive that the information you collect is truly representative of your entire population. We are certainly not condoning sloppy data collection, but as experienced usability professionals are aware, we must strike a balance between rigor and practicality. For example, you should not avoid doing a survey because you cannot obtain a perfect sample. However, when using a convenience sample, still try to make it as representative as you can.

Determining Participant Incentives

Before you can begin recruiting participants, you need to identify how you will reward people for taking time out of their day to provide you with their expertise. You should always provide your participants with an incentive to thank them for their time and effort. The reality is that it also helps when recruiting; but you don’t want your incentive to be the sole reason why people are participating, and you should not make the potential participants “an offer they cannot refuse” (refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, “Appropriate Incentives” section, page 100).

Generic users

When we use the term “generic users,” we are referring to people who participate in a usability activity, but have no ties to your company. They are not customers and they are not employees of your company. They have typically been recruited via an electronic community bulletin board advertisement or an internal database of potential participants, and they are representing themselves, not their company, at your session (this is discussed further in “Recruitment Methods” below). This is the easiest group to compensate because there is no potential for conflicts of interest. You can offer them whatever you feel is appropriate. Some standard incentives include:

![]() One of your company products for free (e.g., a piece of software)

One of your company products for free (e.g., a piece of software)

![]() A gift certificate (e.g., an electronics store, a department store, movie pass)

A gift certificate (e.g., an electronics store, a department store, movie pass)

Cash is often very desirable to participants, but it can be difficult to manage if you are running a large number of studies with many participants. Obviously, you will want to make sure that you have a secure place to store this. Also, if you are working for a large company that requires purchase orders to track money spent, you will not be able to place a purchase order for cash. If you work for a smaller company this may be a manageable option.

In our experience we have found a gift check to be a great alternative to cash. We typically purchase gift checks from American Express. They can be bought in denominations of $10 up to $100. These gift checks can be used like travelers’ checks. Participants can spend them at any place that takes American Express, or they can be cashed/deposited at a bank. We have found that these work well for both participants and ourselves.

With regard to how much to pay participants, this varies a great deal. In the San Francisco Bay area we typically use the formula of $50 per hour; however, we vary this formula depending on how difficult the particular user profile is to recruit or how specialized their skill set is. For example, we may pay students $75 for a two-hour study, but pay doctors $200 for the same session. One thing to keep in mind is that you want to pay everyone involved in the same session the same amount. We sometimes come across the situation where it is easy to get the first few participants, but difficult to get the last few. Sometimes we are forced to increase the compensation in order to entice additional users. If you find yourself in such a situation, remember that you must also increase the compensation for those you have already recruited. A group session can become very uncomfortable and potentially confrontational if, during the activity, someone casually says “This is a great way to make $100” to someone who you offered a payment of only $75. You do not want to lose the trust of your participants and potential end users – that isn’t worth the extra $25.

For highly paid individuals (e.g., CEOs), you could never offer them an incentive close to their normal compensation. For one study, a recruiting agency offered CEOs $500 per hour but they could not get any takers. In these cases, a charitable donation in their name sometimes work better. For children, a gift certificate to a toy store or the movies or a pizza parlor tends to go over well (just make sure you approve it with their parents first). Some companies have even offered savings bonds to children, although the parents usually appreciate them more than the kids do.

Customers or your own company employees

If you are using a customer or someone within your company as a participant, you will typically not be able to pay them as you would a generic end user. Paying customers could represent a conflict of interest because this could be perceived as a payoff. Additionally, most activities are conducted during business hours so the reality is that their company is paying for them to be there. The same is true for employees at your own company. Thank customer participants or internal employees with a company logo item of nominal value (e.g., mug, sweatshirt, keychain).

If sales representatives or members of the product team are doing the recruiting for you, make sure they understand what incentive you are offering for customers and why it is a conflict of interest to pay customers for their time and opinions. We recently had an uncomfortable situation in which the product team was recruiting for one of our activities. They contacted a customer that had participated in our activities before and always received logo gear (“swag”). When the product team told them their employees would receive $150, they were thrilled. When we had to inform the customer that this was not true and that they would receive only swag, they were quite offended. No matter what we said, we could not make the customer (or the product team representative) understand the issue of conflict of interest and they continued to demand the same payment as other participants. After we made it clear that this would not happen, they declined to participate in the activity. You never want the situation to get to this point.

Developing a Recruiting Screener

Assuming you have created a user profile (refer to Chapter 2, Before You Choose an Activity, “User Profile” section, page 43), the first step in recruiting is to create a detailed phone screener. A screener is composed of a series of questions to help you recruit participants who match your user profile for the proposed activity.

Screener Tips

There are a number of things to keep in mind when creating a phone screener. They include:

Do not screen via e-mail

It is important for you to talk to the participants, for a number of reasons. Firstly, you want to get a sense of whether or not they truly match your profile, and it is difficult to do this via e-mail. You really need to have a discussion with the individuals. Secondly, you want to make sure that the participants are clear about what the activity entails and what they will be required to do (see “Provide important details”, page 165). If you send this information via e-mail, you cannot be sure that they read and understood those details. Thirdly, you want to get a sense of an individual’s personality. If someone sounds and behaves in a weird fashion on the phone it is probably because they are weird. Fourthly, you will discover that some people are simply interested in the money or that they are trying to sell themselves to you in order to get a job at your company. You want to avoid recruiting these types of people and a phone call can help you do this.

Work with the product team

We cannot emphasize too strongly how important it is to make sure you are recruiting the right users. Your screener is the tool to help with this. Make sure that the product team helps you to develop it. Their involvement will also help instill the sense that you are a team working together, and it will avoid anyone from the product team saying “You brought in the wrong user” after the activity has been completed.

Keep it short

In the majority of cases, a screener should be relatively short. You do not want to keep a potential participant on the phone for more than 10 or 15 minutes. People are busy and they don’t have a lot of time to chat with you. You need to respect that fact. Also, you are very busy and the longer your screener is, the longer it will take you to recruit your participants.

Use test questions

Make sure that your participants are being honest about their experience. We are not trying to say that people will blatantly lie to you (although occasionally they will), but sometimes people may exaggerate their experience level, or they may be unaware of the limitations of their knowledge or experience (thinking they are qualified for your activity when, in reality, they are not).

When recruiting technical users, determine that they have the correct level of technical expertise. You can do this by asking test questions. This is known as knowledge-based screening. For example, if you are looking for people with moderate experience with HTML coding, you might want to ask “What is a CGI script and how have you used it in the past?”

Collect demographic information

Your screener can also contain some further questions to learn more about the participant. These questions typically come at the end, once you have determined that the person is a suitable candidate. For example, you might want to know which university the person attends and whether he/she is full-time or part-time. The university and the student status will not rule the person out from participating, but it is some relevant information that you can compile about the participants that you brought in for the activity. You can use this demographic information to determine the diversity of your population of participants.

Eliminate competitors

Always, always, find out where the potential participants work before you recruit them. You do not want to invite employees from companies that develop competitor products. This usually means companies that develop or sell products that are anywhere close to the one being discussed. Assuming you have done your homework (refer to Chapter 2, Before You Choose an Activity, page 28), you should know who these companies are. You might imagine that, ethically and legally, this would never happen, but it does. We did have a situation where an intern recruited someone from a competitor to participate in an activity; as luck would have it, the participant canceled later on. If this happens to you, call the participant and explain the situation. Apologize for any inconvenience but state that you must cancel the appointment. People will usually understand.

Sending the participants’ profiles to the product team after recruitment can also help avoid this situation. The team may recognize a competitor that they forgot to tell you about. If you are in doubt about a company, a quick web search can usually reveal whether the company in question makes products similar to yours.

Provide important details

Once you have determined that a participant is a good match for the activity, you should provide the person with some important details. It is only fair to let the potential participants know what they are signing up for. (Refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, page 94, to learn more about how to treat participants.) You do not want there to be any surprises when they show up on the day of the activity. Your goal is not to trick people into participating, so be up-front. You want people who are genuinely interested. Here are some examples of things you should discuss:

![]() Obviously, let them know the logistics: time, date, and location of the activity.

Obviously, let them know the logistics: time, date, and location of the activity.

![]() Tell them exactly how they will be compensated.

Tell them exactly how they will be compensated.

![]() Let them know whether it is a group or individual activity. Some people are painfully shy and do not work well in groups. It is far better for you to find out over the phone than during the session. We have actually had a couple of potential participants who declined to participate in a session once they found out it was a group activity. They simply didn’t feel comfortable talking in front of strangers. Luckily, we learned this during the phone interview and not during the session, so we were able to recruit replacements. Conversely, some people do not like to participate in individual activities because they feel awkward going in alone.

Let them know whether it is a group or individual activity. Some people are painfully shy and do not work well in groups. It is far better for you to find out over the phone than during the session. We have actually had a couple of potential participants who declined to participate in a session once they found out it was a group activity. They simply didn’t feel comfortable talking in front of strangers. Luckily, we learned this during the phone interview and not during the session, so we were able to recruit replacements. Conversely, some people do not like to participate in individual activities because they feel awkward going in alone.

![]() Make them aware that the session will be videotaped. Some people are not comfortable with this and would rather not participate.

Make them aware that the session will be videotaped. Some people are not comfortable with this and would rather not participate.

![]() Emphasize that they must be on time. Late participants will not be introduced into an activity that has already started (refer to Chapter 6, During Your User Requirements Activity, “The Late Participant” section, page 211).

Emphasize that they must be on time. Late participants will not be introduced into an activity that has already started (refer to Chapter 6, During Your User Requirements Activity, “The Late Participant” section, page 211).

![]() If your company requires an ID from participants before entry, inform them that they will be required to show an ID before being admitted into the session (see “The Professional Participant,” page 189).

If your company requires an ID from participants before entry, inform them that they will be required to show an ID before being admitted into the session (see “The Professional Participant,” page 189).

![]() Inform them that they will be required to sign a consent/confidential disclosure agreement, and make sure that they understand what these forms are (refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, “Legal Considerations” section, page 103). You may even want to fax the forms to the participants in advance.

Inform them that they will be required to sign a consent/confidential disclosure agreement, and make sure that they understand what these forms are (refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, “Legal Considerations” section, page 103). You may even want to fax the forms to the participants in advance.

Prepare a response for people who do not match the profile

The reality is that not everyone is going to match your profile, so you will need to reject some very eager and interested potential participants. Before you start calling, you should have a response in mind for the person who does not match the profile. It can be an uncomfortable moment, so have something polite in mind to say, and include this in your screener so you do not find yourself lost for words. Simply thank the person for his/her time and interest in the study, and kindly state that he/she does not match the profile for this particular activity. It can be as simple as “I’m sorry, you do not fit the profile for this particular study, but thank you so much for your time.” If the person seems to be a great potential candidate, encourage him or her to respond to your recruitment postings in the future.

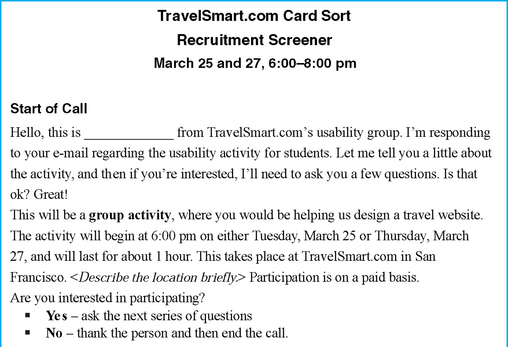

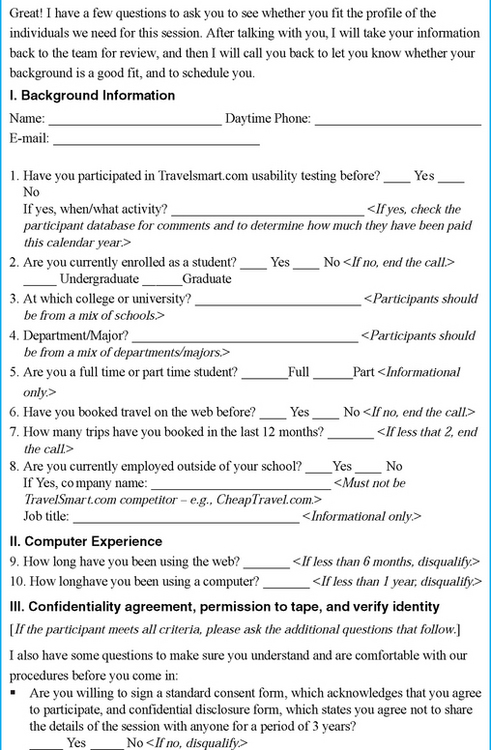

Sample Screener

Figure 5.2 is a sample screener for the recruitment of students for a group card sorting activity. This should give you a sense of the kind of information that it is important to include when recruiting participants.

Creating a Recruitment Advertisement

Regardless of the method you choose to recruit your participants, whether it is via a web posting or an internal database of participants (discussed later in “Recruitment Methods”), you will almost always require an advertisement to attract appropriate end users. Depending on your method of recruiting, you or the recruiter may e-mail the advertisement, post it on a website, or relay its message via the phone. Potential participants will respond to this advertisement or posting if they are interested in your activity. You will then reply to these potential participants and screen them.

There are several things to keep in mind when creating your posting.

Provide details

Provide some details about your study. If you simply state that you are looking for users to participate in a usability study, you will be swamped with responses! This is not going to help you. In your ad, you want to provide some details to help narrow your responses to ideal candidates.

Include logistics

Indicate the date, time, and location of the study. Obviously, by doing so, those who are not available will not respond. You want to weed out unavailable participants immediately.

Cover key characteristics

Indicate some of the key characteristics of your user profile. This will pre-screen appropriate candidates. These are usually high-level characteristics (e.g., job title, company size). You do not want to reveal all of the characteristics of your profile because, unfortunately, there are some people who will pretend to match the profile. If you list all of the screening criteria, deceitful participants will know how they should respond to all of your questions when you call.

For example, let’s say you are looking for people who:

![]() Have purchased at least three airline tickets via the web within the last 12 months

Have purchased at least three airline tickets via the web within the last 12 months

![]() Have booked at least two hotels via the web within the last 12 months

Have booked at least two hotels via the web within the last 12 months

![]() Have booked at least one rental car via the web within the last 12 months

Have booked at least one rental car via the web within the last 12 months

![]() Have experience using the TravelSmart.com website

Have experience using the TravelSmart.com website

In your posting you might indicate that you are looking for people who are over 18, enjoy frequent travel, and have used travel websites.

Don’t stress the incentive

Avoid phrases like “Earn money now!” This attracts people who want easy money and those who will be more likely to deceive you for the cash. Incentives are meant to merely compensate people for their time and effort, as well as to thank them. An individual who is attending your session only for the money will complete your activity as quickly as possible and with as little effort as possible. It really isn’t worth your time and money to bring those individuals in to participate. Trust us.

State how they should respond

We suggest providing a generic e-mail address for interested individuals to respond to rather than your personal e-mail address or phone number. If you provide your personal contact information (particularly a phone number), your voice-mail and/or e-mail inbox will be jammed with responses. Another infrequent but possible consequence is being contacted by desperate individuals wanting to participate and wondering why you haven’t called them yet. By providing a generic e-mail address, you can review the responses and contact whomever you feel will be most appropriate for your activity.

It is also nice to set up an automatic response on the e-mail account, if it is used solely for recruiting purposes. Keep it generic so you can use it for all of your studies. Here is a sample response:

“Thank you for your interest in our usability study! We will be reviewing interested respondents over the next two weeks and we will contact you if we think you are a match for our study.

The TravelSmart.com Usability Group”

Include a link to your in-house participant database

If you have an in-house participant database, you should point participants to your web questionnaire, at the bottom of your ad (see Appendix E, page 704).

Be aware of types of bias

Ideally, you do not want your advertisement to appeal to certain members of your user population and not others. You do not want to exclude true end users from participating. This is easy to do unknowingly based on where you post your advertisement or the content within the advertisement.

For example, let’s say that TravelSmart.com is conducting a focus group for frequent travelers. To advertise the activity you have decided to post signs around local colleges and on college web pages because students are often looking for ways to make easy money. As a result, you have unknowingly biased your sample to people who are in these college buildings (i.e., mostly students) and it is possible that any uniqueness in this segment of the population may impact your product. Make sure you think about bias factors when you are creating and posting your advertisement.

This type of bias, created by those who do not respond to your posting, is referred to as non-responder bias. The “non-responders” are the people who do not respond to your call for participation. Of course there will always be suitable people who do not respond, but if there is a pattern (e.g., those who are not students) then this is a problem. To avoid non-responder bias, you must ensure that your call for participation is perceived equally by all potential users and that your advertisement is viewed by a variety of people from within your user population.

One kind of bias that you are unable to eliminate is self-selection bias. You can reduce this by inviting a random sample of people to complete your survey, rather than having it open to the public; but the reality is that not all people you invite will want to participate. Some of the invited participants will self-select to not participate in your activity.

Sample Posting

Figure 5.3 is a sample posting to give you a sense of how a posting might look when it all comes together.

Recruitment Methods

There are a variety of methods to attract users and each method has its own strengths and weaknesses. If one fails then you can try another. In this section, we will touch on some of these methods so that you can identify the one that will best suit your needs.

Advertise on Community Bulletin Board Sites

Web-based community bulletin boards allow people to browse everything from houses to jobs to things for sale. We have found them to be an effective way to attract a variety of users. We will typically place these ads in the classified section under “Jobs.” You may be able to post for free or for less than $100, depending on the area of the country you live in and the particular bulletin board. The ad is usually posted within 30 minutes from when you submit it. One of the advantages of this method is that it is a great pre-screen if you are looking for people who use the web and/or computers. If they have found your ad, you know they are web users!

If you are looking for people who are local, use a site that is local to your area. Sites such as your local newspaper website or community publications are good choices. We have had great success using Craig’s List in the San Francisco Bay area (see Figure 5.4). It has often proved to be one of our most successful methods of recruitment. If you do not have access to any web publications in your area, or if you want people who do not have web experience, you could post your advertisement in a physical newspaper.

Figure 5.4 Craig’s List in the San Francisco Bay Area (www.craigslist.org)

Create an In-house Database

You can create a database within your company where you maintain a list of people who are interested in participating in usability activities. This database can hold some of the key characteristics about each person (e.g., job title, years of experience, industry, company name, location, etc.). Prior to conducting an activity, you can search the database to find a set of potential participants who fit your user profile. See Appendix E (page 704) for a discussion of how to set up such a database.

Once you have found potential participants, you can e-mail them some of the information about the study and ask them to e-mail you if they would like to participate. The e-mail should be similar to an ad you would post on a web community bulletin board site (see Figure 5.3 on page 173). State that you obtained the person’s name from your in-house participant database, which he/she signed up for, and provide a link or option to be removed from your database. For those who respond, you should then contact them over the phone and run through your screener to check that they do indeed qualify for your study (refer to “Developing a Recruiting Screener,” page 161).

Use a Recruiting Agency

You can hire companies to do the recruiting for you. They have staff who are devoted to finding participants. These companies are often market research firms but, depending on your user type, temporary agencies can also do the work. In the San Francisco Bay area we have used Nichols Research (www.nichols-research.com) and Merrill Research (www.merrill.com). Fieldwork (www.fieldwork.com) is another company that has offices sprinkled throughout the United States. You can contact the American Marketing Association (www.marketingpower.com) to find companies that offer this service in your area. Appendix D (page 698) contains a list of companies that can recruit for activities, conduct them, and rent facilities.

Sounds great, doesn’t it? Well, it certainly can be. We have found that a recruiting service is most beneficial when trying to recruit a user type that is difficult to find.

For example, we needed to conduct a study with physicians. Our participant database did not contain physicians and an electronic community bulletin board posting was unsuccessful. As a result, we went to a recruiting agency and they were able to get these participants for us.

An additional benefit to using recruiting agencies is that they usually handle the incentives. Once you cut a purchase order with the company, you can include money for incentives. The recruiting agency will then be responsible for paying the participants at the end of a study. This is one less thing for you to worry about.

You might ask: “Why not use these agencies exclusively and save time?” One of the reasons is cost. Typically they will charge anywhere from $100 to $200 to recruit each participant (not including the incentives). The price varies depending on how hard they think it will be for them to attract the type of user you are looking for. If you are a little more budget conscious, you might want to pursue some of the other recruiting options; but keep in mind that your time is money. A recruiting agency might be a bargain compared to your own time spent recruiting.

Also, in our experience, participants recruited by an agency have a higher no-show rate. One reason for this is that not all agencies call to remind the participants about the activity the day before (or on the day of) the study. Additionally, using a recruiting agency adds a level of separation between you and the participants – if you do the recruiting yourself, they may feel more obligated to show up.

We should note, however, that not all usability professionals we have spoken with share our negative experience with recruiting agencies. Some have told us that their no-show rates have been very low when working with recruiting agencies.

Some recruiting agencies need more advance notice to recruit than we normally need ourselves. Some agencies we have worked with required a one-month notice to recruit so they had enough resources lined up. Consequently, if you need to do a quick, lightweight activity, an agency might not be able to assist you, but it never hurts to enquire.

Lastly, we have found that agencies are not effective in recruiting very technical user types. Typically, the people making the calls will not have domain knowledge about the product you are recruiting for. Imagine you are conducting a database study and you require participants who have an intermediate level of computer programming knowledge. You have devised a set of test questions to assess their knowledge about programming. Unless these questions have very precise answers (e.g., multiple-choice), the recruiter will not be able to assess whether the potential participant is providing the correct answers. A participant may provide an answer that is close enough, but the recruiter doesn’t know that. Even having precise multiple-choice answers doesn’t always help. Sometimes the qualifications are so complex that you simply have to get on the phone with candidates.

Regardless of these issues, a recruiting agency can be extremely valuable. If you decide to use one, there are a few things to keep in mind.

Provide a screener

You will still need to design the phone screener and have the product team approve it. The recruitment agency will know nothing about your product, so the screener may need to be more detailed than you would normally provide. Indicate what the desired responses are for each question, and when the phone call should end because the potential participant does not meet the necessary criteria. Also provide a posting, if they are going to advertise to attract participants.

Be sure to discuss the phone screener with the recruiter(s). Don’t just send it via email and tell them to contact you if they have any questions. You want to make sure that they understand and interpret each and every question as it was intended. Even if you are recruiting for a user with a non-technical profile, make sure you do this. You may even choose to do some role-playing with the recruiter. Only when the recruiter begins putting your screener to work will you see whether he/she really understands it. Many research firms will employ a number of people to make recruitment calls. If you are unable to speak with all of them then you should speak with your key point of contact at the agency and go through the screener.

Ask for the completed screeners to be sent after each person is recruited

This is a way for you to monitor who is being recruited and to double-check that the right people are being signed up. You can also send the completed screeners along to members of the product team to make sure they are happy with each recruit. This has been very successful for us in the past.

Ensure that they remind the participants

It sounds obvious, but reminding participants of your activity will drastically decrease the no-show rate. Sometimes recruiting agencies recruit participants one to two weeks before the activity. You want to make sure that they call to remind people on the day before (and possibly again on the day of) the activity to get confirmation of attendance. It is valuable to include reminder calls in your contract with the recruitment agency, which also states that you will not pay for no-shows. This increases their motivation to get those participants in your door.

Avoid the professional participant

Yes, even with recruitment agencies, you must avoid “the professional participant.” A recruitment agency may call on the same people over and over to participate in a variety of studies. We have encountered this. The participant may be new to you but could have participated in three other studies this month. Although the participant may meet all of your other criteria, someone who seeks out research studies for regular income is not representative of your true end user. They will likely behave differently and provide more “polished” responses if they think they know what you are looking for.

You can insist that the recruitment agency provide only “fresh” participants. To double-check this, chatting with participants at the beginning of your session can reveal a great deal. Simply ask: “So, how many of you have participated in studies for the ABC agency before?” People will often be proud to inform you that the recruiting agency calls on them for their expertise “all the time.”

You can’t always add them to your database

You may be thinking that you will use a recruiting agency to help you recruit people initially and then add those folks to your participant database for future studies (see Appendix E, page 704). In many cases, you will not be able to do this. Some recruiting agencies have a clause in their contract that states that you cannot enlist any of the participants they have recruited unless it is done via them. Make sure you are aware of this clause, if it exists.

Make Use of Customer Contacts

Current or potential customers can make ideal participants. They truly have something at stake because, at the end of the day, they are going to have to use the product. As a result, they will likely not have problems being honest with you. Sometimes they are brutally honest.

Typically, a product team, a sales consultant, or account manager will have a number of customer contacts with whom they have close relationships. The challenge can be convincing them to let you have access to them. Often they are worried or concerned that you may cause them to loose a deal or that you might upset the customer. Normally, a discussion about your motives can help alleviate this problem.

Start by setting up a meeting to discuss your proposal (see “Getting commitment,” page 153). Once the product team member, sales consultant, or account manager understands the goal of your user requirements activity, they will hopefully also see the benefits of customer participation. It is a “win–win” situation for both you and the customer. Customers love to be involved in the process and having their voices heard, and you can collect some really great data. Another nice perk is that it can cost you less, as you typically provide only a small token of appreciation rather than money (see “Determining Participant Incentives,” page 159).

Despite your efforts, it is possible that you will be forbidden from talking with certain customers. You will have to live with this. The last thing you want is to make an account manager angry, or cause a situation in which a customer calls up your company’s rep to complain that they want what the usability group showed them, not what the rep is selling. The internal contacts within your company can be invaluable when it comes to recruiting customers – they know their customers and can assist your recruiting – but they have to be treated with respect and kept informed about what you are doing.

If you decide to work with customers, there are several things to keep in mind.

Be wary of the angry customer

When choosing customers to work with, it is best to choose ones who currently have a good relationship with your company. This will simply make things easier. You want to avoid situations that involve heavy politics and angry customers. The last thing you or your group needs is to be blamed for a spoiled business deal. However, deals have actually been saved as a result of intervention from the usability professionals – the customer appreciated the attention they were receiving and recognized that the company was trying to improve the product based on their feedback. If you find yourself dealing with a dissatisfied customer, give the participants an opportunity to vent; however, do not allow this to be the focus of your activity. Providing 15 minutes at the beginning of a session for a participant to express his/her likes, dislikes, challenges, and concerns can allow you to move on and focus on the desired requirements gathering activity you planned.

When recruiting customers, if you get a sense that the customer may have an agenda, plan a method to deal with this. Customers often have gripes about the current product and want to tell someone. One way to handle this is to have them meet with a member of the product team in a separate meeting from the activity. The usability engineer needs to coordinate this with the product team. It requires additional effort, but it helps both sides.

Avoid the unique customer

It is best to work with a customer that is in-line with most of your other customers. Sometimes there are customers that have highly customized your product for their unique needs. Some companies have business processes that differ from the norm or industry standards. If you are helping the product development team collect user requirements for a “special customer,” this is fine. If you are trying to collect user requirements that are going to be representative of the majority of your user population, you will not want to work with a customer that has processes different from the majority of potential users.

Recruiting internal employees

Sometimes your customers are people who are internal to your company. These can be the hardest people of all to recruit. In our experience, they are very busy and just don’t feel it is worth their time to volunteer. If you are attempting to recruit internal participants, we have found it extremely effective to get their management’s buy-in first. That way, when you contact them, you can say “Hi John, I am contacting you because your boss, Sue, thought you would be an ideal candidate for this study.” If their boss wants them to participate they are unlikely to decline.

Allow more time to recruit

Unfortunately, this is one of the disadvantages of using customers. Typically, customer recruiting can be a slow process. There is often corporate red tape that you need to go through. You may need to explain to a number of people what you are doing and whom you need to participate. You also need to rely on someone within the company to help you get access to the right people. The reality is that although this may be your top priority, in most cases it is not their’s, so things will always move more slowly than you would like. You may also have to go through the legal department for both your company and the customer’s in order to get approval for your activity. Confidential disclosure agreements may need to be changed (refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, “Legal Considerations” section, page 103).

Make sure the right people are recruited

You need to ensure that your company contact is crystal-clear about the participants you need. In most cases, the contact will think that you want to talk to the people who are responsible for purchasing or installing the software. Make sure the person understands that you want to talk to the people who will be using the software after it has been purchased and installed. It is best not to hand your screener over to the customer contact. Instead, provide the person with the user profile (refer to Chapter 2, Before You Choose an Activity, “User Profile” section, page 43) and have him/her e-mail you the names and contact information of people seeming to match this profile. You can then contact them yourself and run them through your screener to make sure they qualify.

It is important to note that companies often want to send their best and brightest people. As a result it can be difficult to get a representative sample with customers. You should bring this issue up with the customer contact and say: “I don’t want only your best people. I want people with a range of skills and experience.”

Also, don’t be surprised if the customer insists on including “special” users in your study. Often, supervisors will insist on having their input heard before you can access their employees (the true end users). Even if you don’t need feedback from purchasing decision-makers or supervisors, you may have to include them in your activity. It may take longer to complete your study with additional participants, but the feedback you receive could be useful. At the very least, you have created a more positive relationship with the customer by including those “special” users.

Preventing No-shows

Regardless of your recruitment method, you will encounter the situation where people who have agreed to participate do not show up on the day. This is very frustrating. The reason could be that something more important came up, or the participant might have just completely forgotten. There are some simple strategies to try and prevent this from occurring.

Provide contact information

Participants are often recruited one to two weeks before the activity begins. When we recruit, participants are given a contact name and phone number and told to contact this person if they will not be able to make the session for any reason. We understand that people do have lives and that our activity probably ranks low in the grand scheme of things. We try to emphasize to participants that we really want them to participate, but we will understand if they cannot make the appointment. We really appreciate it when people take the time to call and cancel or reschedule. It allows us an opportunity to find someone else, or to reschedule. It is the people who just do not appear that cause the most difficulty.

Remind them

The day before, and on the day of the activity, contact the participants to remind them. Some people just simply forget, especially if it is on a Monday morning! A simple reminder can prevent this.

Try to phone people rather than e-mail them, because you need to know whether or not they will be coming. If you catch them on the phone you can get this immediately. Also, you can reiterate a couple of very important points to them. Remind them that they must be on time for the activity, and they must bring a valid driver’s license or they will not be admitted to the session. If you send an e-mail, you will have to hope that people read it carefully and take note of these important details. Also, you will have to wait for people to respond to confirm. Sometimes people do not read your e-mail closely and they do not respond (especially, if they know they are not coming). If participants cannot be reached by phone, and you must leave a voice-mail, remind them about the date and time of the session, and all of the other pertinent details. Ask them to call you back to confirm their attendance.

Over-recruit

Even though you have provided your participants with contact information to cancel and you have called to remind them, there are still people who will not show up. To counteract this problem, you can over-recruit participants. It is useful to recruit one extra person for every four or five participants needed.

Sometimes everyone will show up, but we feel this cost is worth it. It is better to have more people than not enough. When everyone shows, you can deal with this in a couple of ways. If it is an individual activity, you can run the additional sessions (it costs more time and money but you get more data) or you can call and cancel the additional sessions. If participants do not receive your cancellation message in time and they appear at the scheduled time, you should pay them the full incentive for their trouble.

If everyone shows up for a group activity, we typically keep all participants. An extra couple of participants will not negatively impact your session. If there is some reason why you cannot involve the additional participants, you will have to turn them away. Be sure to pay them for their trouble.

Some people double-book every slot for an individual activity. They will involve the first person who arrives, and if the second person shows up then he/she will be paid but turned away. Unless you are under a very strict deadline, or the user profile is expected to have a very high no-show rate, we do not recommend using this method – primarily because you have to spend twice as long recruiting and pay twice as much for your participants. Also, it is never very nice to have to turn people away. You do not want to set yourself up so that you are potentially turning away half of your participants. That is no way to create a loyal following of participants.

Recruiting International Participants

Depending on the product you are working on and its market, you may need to include participants from other countries. You cannot assume that you can recruit for or conduct the activity in the same manner as you would in your own country. Below are some pieces of advice to keep in mind when conducting international user requirements activities (Dray & Mrazek 1996).

![]() Use a professional recruiting agency in the country where you will be conducting the study. It is highly unlikely you will know the best places or methods for recruiting your end users.

Use a professional recruiting agency in the country where you will be conducting the study. It is highly unlikely you will know the best places or methods for recruiting your end users.

![]() Learn the cultural and behavioral taboos/expectations. The recruiting agency can help you, or you can check out several books specifically for this. Refer to “Suggested Resources for Additional Reading” on page 186 for more information.

Learn the cultural and behavioral taboos/expectations. The recruiting agency can help you, or you can check out several books specifically for this. Refer to “Suggested Resources for Additional Reading” on page 186 for more information.

![]() If your participants speak another language, unless you are perfectly fluent you will need a translator. Even if your user speaks your language, you will need a translator. The participants will likely be more comfortable speaking in their own language or could have some difficulty understanding some of your terminology if they are not fluent. There are often slang or technical terms that you will miss out on, despite being well-versed in the foreign language.

If your participants speak another language, unless you are perfectly fluent you will need a translator. Even if your user speaks your language, you will need a translator. The participants will likely be more comfortable speaking in their own language or could have some difficulty understanding some of your terminology if they are not fluent. There are often slang or technical terms that you will miss out on, despite being well-versed in the foreign language.

![]() If you are doing in-home studies in Europe, in some countries not only is it unusual to go to someone’s home for an interview or other activity, it is also unusual for guests to bring food to someone’s home. Since you are a foreigner, or because the study is unusual, bringing food will likely be accepted.

If you are doing in-home studies in Europe, in some countries not only is it unusual to go to someone’s home for an interview or other activity, it is also unusual for guests to bring food to someone’s home. Since you are a foreigner, or because the study is unusual, bringing food will likely be accepted.

![]() Punctuality can be an issue. For example, you must be on time when observing participants in Germany. In Korea or Italy, however, time is somewhat relative – appointments are more like suggestions and very likely will not begin on time. Keep this in mind when scheduling multiple visits in one day.

Punctuality can be an issue. For example, you must be on time when observing participants in Germany. In Korea or Italy, however, time is somewhat relative – appointments are more like suggestions and very likely will not begin on time. Keep this in mind when scheduling multiple visits in one day.

![]() Pay attention to holiday seasons. For example, you will be hard pressed to find European users to observe in August since many Europeans go on vacation at that time. Countries with a large Islamic population will likely be unavailable during Ramadan.

Pay attention to holiday seasons. For example, you will be hard pressed to find European users to observe in August since many Europeans go on vacation at that time. Countries with a large Islamic population will likely be unavailable during Ramadan.

Recruiting is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to conducting international field studies. You cannot simply apply a user research method in a foreign country in the same way that you would in your own country. At the end of this chapter you will find a fascinating case study from Kaizor Innovation that discusses issues relating to applying western research methods in China. If you plan to conduct international user requirements activities you will gain a tremendous amount of beneficial information that can be applied to your particular situation.

Recruiting Special Populations

There are a number of special considerations when recruiting special populations of users. These populations can include such groups as children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. This section discusses some things to consider.

Transportation

You may need to arrange transportation for people who are unable to get to the site of the activity. You should be prepared to arrange for someone to pick them up before the activity and drop them off at the completion of the activity. This could be done using taxis, or you could arrange to have one of your employees do it. Also, if it is possible, you should consider going to the participant rather than having him or her come to you.

Escorts

Some populations may require an escort. For example, in the case of participants under the age of 18, a legal guardian must accompany them. You will also need this guardian to sign all consent and confidential disclosure forms. You may also find that adults with disabilities or the elderly may require an escort. This is not a problem. If the escort is present when the user requirements session is being conducted, simply ask him/her to sit quietly and not interfere with the session. It is most important for the participant to be safe and feel comfortable (refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, “Ethical Considerations” section, page 95). This takes priority over everything else.

Facilities

Find out whether any of your participants have special needs with regard to facilities as soon as you recruit them. If any of your participants have physical disabilities, you must make sure that the facility where you will be holding your activity can accommodate people with disabilities. You will want to ensure that it has parking for the handicapped, wheelchair ramps, and elevators, and that the building is wheelchair accessible in all ways (bathroom, doorways, etc.). Also keep in mind that the facility may need to accommodate a dog if any of your participants use one as an aid.

If you are bringing children to your site it is always a nice idea to make your space “kid friendly.” Put up a few children’s posters. Bring a few toys that they can play with during a break. A few small touches can go a long way to helping child participants feel at ease.

Tracking Participants

When recruiting via an electronic community bulletin board posting, recruiting agency, or an in-house database, there are a number of facts about the participants that you need to track. To help you accomplish this, set up a database that lists all of the participants that you use. This can be the beginning of a very simple participant database. You will want to track such things as:

![]() The activities they have participated in

The activities they have participated in

![]() Any negative comments regarding your experience with the participant (e.g., “user did not show up,” “user did not participate,” “user was rude”)

Any negative comments regarding your experience with the participant (e.g., “user did not show up,” “user did not participate,” “user was rude”)

You may also want to check with your legal department whether you can collect participants’ social security numbers. It is a great piece of information to have because it is a unique identifier for each participant. However, it tends to deter participation. May people are very protective of this information (as they should be!) and would rather not participate if it requires providing their social security number. This may also cause participants to distrust your motives.

Tax Implications

If any participant is paid over $600 in one calendar year in the United States, your company will be required to complete and submit a 1099 tax form. Failure to do so can get your company (and possibly even the person who hands out the money) into serious trouble. This is a real headache and you will do yourself a big favor by avoiding this. To do so, you will need to track how much each participant has been paid each calendar year. Once a participant reaches the $600 mark, move him/her to a Watch List (see below). This list should be reviewed by the recruiter prior to recruiting.

The Professional Participant

Believe it or not, there are people who seem to make a career out of participating in usability activities and market research studies. Some are just genuinely interested in your studies, but others are genuinely interested in the money. You definitely want to avoid recruiting the latter.

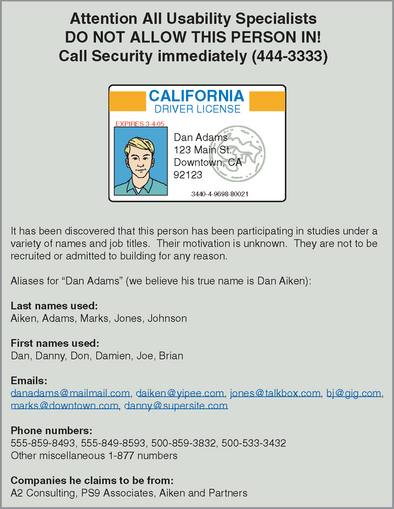

We follow the rule that a person can participate in an activity once every three months or until he or she reaches the $600/year mark (see “Tax Implications,” page 188). Unfortunately, there are some people who don’t want to play by these rules. We have come across people who have changed their names and/or job titles in order to be selected for studies. We are not talking about subtle changes. In one case, we had a participant who claimed to be a university professor one evening and a project manager another evening – we have compiled at least nine different aliases, phone numbers, and e-mail addresses for this participant! The good news is that these kinds of people tend to be the rare exception.

By tracking the participants you have used in the past, you can take the contact information you receive from your recruits and make sure that it does not match the contact information of anyone else on your list. When we discover people who are using aliases, or who we suspect are using aliases, we place them on a Watch List (see below).

We also attempt to prevent the alias portion of the problem by making people aware during the recruiting process that they will be required to bring a valid government-issued ID (e.g., drivers license, passport). If they do not bring their ID, they will not be admitted into the activity. You need to be strict about this. It is not good enough to fax a photocopy or send an e-mail of the license before or after the activity. The troublesome participant described above actually altered her driver’s license and e-mailed it to us to receive the incentive she had been denied the night before.

Create a Watch List

The Watch List is an important item in your recruiting toolbox. It is where you place the names of people you have recruited in the past, but do not want to recruit in the future. These people can include:

![]() Those who have reached the $600 per calendar year payment limit (you can remove them from the watch list on January 1st)

Those who have reached the $600 per calendar year payment limit (you can remove them from the watch list on January 1st)

![]() Those who have been dishonest in any way (e.g., used an alias; changed job role without a clear explanation)

Those who have been dishonest in any way (e.g., used an alias; changed job role without a clear explanation)

![]() Those who have been poor participants in the past (e.g., rude; did not contribute; showed up late)

Those who have been poor participants in the past (e.g., rude; did not contribute; showed up late)

The bottom line is that you want to do all you can to avoid bringing in undesirable participants. Again, in the case of our troublesome participant, she managed to sweet-talk her way into more than one study without a driver’s license (“I left it in my other purse,” and “I didn’t drive today”). As a result, we posted warning signs for all usability engineers in our group. We even included her picture from the forged ID she e-mailed us. See Figure 5.5 on page 190 for an example of a “Wanted” poster.

Creating a Protocol

A protocol is a script that outlines all procedures you will perform as a moderator and the order in which you will carry out these procedures. It acts as a checklist for all of the session steps.

The protocol is very important for a number of reasons. Firstly, if you are running multiple sessions of the same activity (e.g., two focus groups) it ensures that each activity and each participant is treated consistently. If you run several sessions, you tend to get tired and may forget details. The protocol helps you keep the sessions organized and polished. If you run the session differently for each activity, you will impact the data that you receive for each session. For example, if the two groups receive different sets of instructions, each group may have a different understanding of the activity and hence produce different results.

Secondly, the protocol is important if there is a different person running each session. This is never ideal, but the reality is that it does happen. The two people should develop the protocol together and rehearse it.

Thirdly, a protocol helps you as a facilitator to ensure that you relay all of the necessary information to your participants. There is typically a wealth of things to convey during a session and a protocol can help ensure that you cover everything. It could be disastrous if you forgot to have everyone sign your confidential disclosure agreements – and imagine the drama if you forgot to pay them at the end of the session.

Finally, a protocol allows someone else to replicate your study, should the need arise.

Sample Protocol

Figure 5.6 is a sample protocol for a group card sorting activity. Of course, you need to modify the protocol according to the activity you are conducting, but this one should give you a good sense of what it should contain.

Piloting Your Activity

A pilot is essentially a practice run for your activity. It is a mandatory element for any user requirements activity. These activities are complex, and even experienced usability specialists always conduct a pilot. You cannot conduct a professional activity without a pilot. It is more than “practice,” it is debugging. Run the activity as though it is the true session. Do everything exactly as you plan to for the real session. Get a few of your co-workers to help you out. If you are running a group activity that requires 12 people, you do not need to get 12 people to participate in the pilot. (It would be great if you could, but it usually is not realistic or necessary.) Three or four co-workers will typically help you accomplish your purpose. We recommend running a pilot about three days before your session – this will give you time to fix any problems that crop up.

Conducting a pilot can help you accomplish a number of goals.

Is the audio-visual equipment working?

This is your chance to set camera angles, check microphones, and make sure that the quality of recording is going to be acceptable. You don’t want to find out after the session that the video camera or tape recorder was not working.

Clarity of instructions and questions

You want to make sure that instructions to the participants are clear and understandable. By trying to explain an activity to co-workers ahead of time, you can get feedback about what was understandable and what was not so clear.

Find bugs or glitches

A fresh set of eyes can often pick up bugs or glitches that you have not noticed. These could be anything from typos in your documentation to hiccups in the product you plan to demo. You will obviously want to catch these embarrassing oversights or errors before your real session.

Practice

If you have never conducted this type of activity before, or it has been a while, a pilot offers you an opportunity to practice and get comfortable. A nervous or uncomfortable facilitator makes for nervous and uncomfortable participants. The more you can practice your moderation skills the better (refer to Chapter 6, During Your User Requirements Activity, “Moderating Your Activity” section, page 220).