DURING YOUR USER REQUIREMENTS ACTIVITY

Introduction

In the previous chapter you learned how to lay the groundwork and prepare for any activity. Getting the right participants and preparing for the activity is critical; but what happens during the activity is just as important, if not more so to the success of your activity. In this chapter, we cover the fundamentals that you must be aware of in order to execute a successful user requirements activity.

Welcoming Your Participants

Asking participants to arrive about 15 minutes before the session is due to begin (30 minutes if you are serving dinner) allows enough time for participants to get some food, relax, and chat. In the case of a group session, it also provides a buffer in case some participants are running late. We tell participants during recruitment (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Recruitment Methods” section, page 173): “The session starts at 6:00 pm; please arrive 30 minutes ahead of time in order to eat, and to take care of administrative details before the session starts. Late participants will not be admitted into the session.”

During this pre-session period, you can introduce yourself, give a quick overview of the session’s activities, and explain the confidential disclosure agreement and consent form (refer to chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, page 94). Playing an audio CD during this time can provide a casual atmosphere and is more pleasant than the sound of uncomfortable silence or of forks scraping plates.

If it is a group session, during this pre-session period, a co-worker should be in the lobby by a “Welcome” sign on a flip chart to greet and direct participants as they arrive. Such a sign might read: “Welcome to the participants of the TravelSmart.com focus group. Please take a seat and we will be with you shortly.” This sign lets participants know they are in the right place and directs them what to do in the case that the greeter is not present. If your location has a receptionist, to avoid confusion, provide the receptionist with your participant list and make sure the receptionist asks all participants to stay in a specified location. We have had the distressing task of trying to locate a wayward participant when a receptionist was trying to be helpful and sent the participant off in the wrong direction to find us. This doesn’t start the session off on the right foot. If your location does not have a receptionist, put up a large sign that specifies where participants should wait in case people arrive while others are being escorted to the activity location.

It saves time and effort to bring participants to the session location in groups of four or five. Make sure to ask participants if they need to use the bathroom along the way to avoid having to make multiple trips back and forth.

Dealing with Late and Absent Participants

You are sure to encounter participants who are late or those who simply do not show up. In this section we discuss how to deal with and prevent these situations.

The Late Participant

You are certain to encounter late participants in both group and individual activities. We do our best to emphasize to participants during the recruiting phase that being on time is critical – and if they are late, they will not be admitted to the session. We emphasize this again when we send them e-mail confirmations of the activity and when we call them back to remind them about the session the night before. It is also a good idea to make them aware of any traffic or parking issues in your area that may require extra time.

However, through unforeseen traffic problems, getting lost, and other priorities in peoples’ lives, you will often have a participant who arrives late despite your best efforts. Thanks to cell-phones, many late participants will call to let you know they are on their way. If it is a group activity and you have some extra time, you can try to stall while you wait for the person to show up. If it is an individual activity your ability to involve a late participant may depend on the flexibility of your day’s schedule. We typically have a one-hour cushion between participants, so a late participant is not a problem. Thanks to your cushion you should be able to accommodate him/her.

For group sessions, we will typically build-in a 15-minute cushion knowing that some people will arrive late. It is not fair to make everyone wait too long just because one or two people are late. If it is an evening session and we are providing food, we ask participants to arrive 30 minutes earlier than the intended session time to eat. This means that if people arrive late, it will not interfere with your activity. They will just have less time (or no time) to eat.

You Can’t Wait Any Longer

In the case of a group activity, at some point you will need to begin your session whether or not all of your participants are present. The reality is that some participants never show, so you don’t want to waste your time waiting for someone who is not going to appear.

After 15 minutes, if a participant does not appear, leave a “late letter” (see Figure 6.1) in the lobby with the security guard or receptionist. For companies that don’t have someone employed to monitor the lobby on a full-time basis, you may wish to arrange ahead of time to have a co-worker volunteer to wait in the lobby for 30 minutes or so for any late participants. Alternatively, you can leave a sign (like the “Welcome” sign) that says something like: “Participants for the SmartTravel.com

Focus Group: The session began at 5 pm and we are sorry that you were unable to arrive in time. Because this is a group activity, we had to begin the session. We appreciate your time and regret your absence.”

You should provide an incentive in accordance with the policy you stated during recruitment. If you do not plan to pay participants if they are more than 15 minutes late, you should inform them of this during recruitment. However, you may wish to offer a nominal incentive or the full incentive to participants who are late as a result of bad weather, bad traffic, or other unforeseeable circumstances. Just decide prior to the activity, inform participants during recruiting, and remain consistent in the application of that policy.

Inform the security guard or receptionist that late participants may arrive but you cannot include them in the activity. Or, as mentioned, you can also assign someone to wait in the lobby and fulfill this role. Tell him/her to hand out the late letter and incentive to the participant if they should show up. Make sure you tell whomever is waiting to greet the late participants to ask for identification before providing the incentive (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “The Professional Participant” section, page 189). It is also advisable to have that person ask the participant to sign a sheet of paper confirming that the incentive was received.

As an additional alternative, leave the late participant a voice-mail on the cell-phone and home or work phone. State the current time and politely indicate that because the person is late, he/she cannot be admitted to the session. Leave your contact information and state that the person can receive an incentive (if appropriate) by coming back to your facility at his/her convenience and showing a driver’s license (if ID is one of your requirements).

Including a Late Participant

There are some situations where you are unable to turn away a late participant. These situations may include: a very important customer who you do not want to upset, or a user profile that is very difficult to recruit and you need every participant you can get.

Again, for individual sessions (e.g., interviews) we typically have about an hour cushion between participants so a latecomer is not that big a deal. For group sessions, it is a little more difficult to include latecomers. If they arrive just after the instructions have been given, you (or ideally someone working with you) can pull them aside and get them up to speed quickly. This is by no means ideal, but it can be done fairly easily and quickly for most user requirements activities.

If the participant arrives, the instructions have been given, and the activity itself is well underway, you can include them, but you may have to disregard their data. Obviously, if you know you are going to throw away the person’s data, you would only want to do this in cases where it is politically necessary to include the participant, not for cases where the participants are hard to get. In cases where participants are hard to come by, make sure you reschedule the participant(s). Don’t waste their time and yours by including them and then throwing away the data. But do keep in mind if you reschedule them that participants who are late once are more likely to be late again or be no-shows. If it is an activity such as a group task analysis (refer to chapter 11, Group Task Analysis, page 458) where adding a participant in the middle of the flow can have a serious impact, you may want to consider having the user create their own flow independent of the group. In these cases, you will need a co-worker to do more than give instructions; he or she will have to moderate the session and collect the data.

The No-show

Despite all of your efforts, you may encounter no-shows. These are the people who simply do not show up for your activity without any warning. We have found that for every 10 participants, one or two will not show up. This may be because something important came up and you are the lowest priority, or the person may have just completely forgotten. chapter 5 discusses a number of measures that you can take to deal with this problem (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Preventing No-shows” section, page 182). Essentially:

![]() Provide recruited participants with your contact information so that they can contact you if needing to cancel or reschedule.

Provide recruited participants with your contact information so that they can contact you if needing to cancel or reschedule.

![]() Remind participants of the activity and ask them to re-confirm a day or two prior to the activity.

Remind participants of the activity and ask them to re-confirm a day or two prior to the activity.

![]() Whatever number of participants you decide upon, recruit about one extra participant for every five that you would like to attend. This is to account for late cancellations (which don’t leave you enough time to recruit someone else) and no-shows.

Whatever number of participants you decide upon, recruit about one extra participant for every five that you would like to attend. This is to account for late cancellations (which don’t leave you enough time to recruit someone else) and no-shows.

Warm-up Exercises

When conducting any kind of user activity, ensure that your participants are comfortable and feeling at ease before you begin. When conducting an individual activity, start out with some light conversation in the lobby and as you move towards your destination. Comment on the weather; ask whether the person had any trouble with traffic or parking. Keep it casual. When you sit down to begin the session, start with an informal introduction of yourself and what you do. Ask the participant to do the same. Also find out what you should call the person, and then use first names if appropriate.

Ensuring that participants are at ease is extremely important for group activities. Each person will typically need to interact with you and everyone else in the room, so you want to make sure they feel comfortable with this. This is particularly important when the group has not worked together before. Typically, we give people colorful markers and nametags or name tents. We ask them to write their names and draw something that describes their personality on the tag. (For example, if I like to play golf, I might draw some golf clubs on my nametag.) During this time, the moderators should also create nametags for themselves. Once everyone has finished this, the moderators should explain what they have drawn on their own nametags and why. This will help to put the first participant at ease when he/she describes his/her nametag, and so on around the room. Any type of warm-up activity that gets people talking will do.

The nametag activity is great because it serves a two-fold purpose: it helps everyone relax, and it helps you get exposure to each person’s name. You will want to use people’s names as much as possible throughout the session, to make the session more personal.

You can use any kind of warm-up activity that you feel works best for you. Some people like to have people spend a few minutes talking about what they like and dislike about the current product they are using. Whatever activity you use, you should keep in mind that this is not intended to take a long time. You just want to do something to get everyone talking and to get those creative juices flowing. Fifteen minutes should be plenty of time to accomplish this.

Inviting Observers

By the term “observer” we mean someone who does not have an active role during the activity. If you have the appropriate facilities, invite stakeholders to view your user requirements sessions. Having appropriate facilities means that the observers are watching, but their presence is not known to the participants (e.g., behind a one-way mirror).

To learn about setting up facilities that are appropriate for observers, see chapter 4 (refer to chapter 4, Setting up Facilities for Your User Requirements Activity, page 106).

Having observers in the same room as the participants will only serve to distract, disrupt, and/or intimidate participants. We recently conducted a focus group where the product team wanted to have 15 members of the team sitting in the back of the room. This was more than the number of participants in the session! After explanation of the potential for disruption (e.g., from whispering, getting up to take calls, or going to the bathroom) they were happy to observe from another room.

Development teams often think they know all of the user requirements, but sometimes they need to attend to see how much or how little they know. Observers can learn a lot about what users like and dislike about the current product or a competitor’s product, the difficulties they encounter, what they want, and why they think they want it by observing user requirements activities. Watching a usability activity has a far greater impact than reading a usability report alone.

Another advantage of inviting observers is team-building. You are all part of a “team” so stakeholders should be present at the activities too. Also, it helps stakeholders understand what you do and what value you bring to the team – and that builds credibility. It is also wise to record sessions for anyone who may not be able to attend, as well as for your own future reference.

When you invite observers it is a good idea to set expectations up-front:

![]() Tell observers to come early and enter in a manner so that they are not seen by the participants.

Tell observers to come early and enter in a manner so that they are not seen by the participants.

![]() They will need to be quiet. Often, rooms divided by a one-way mirror might not be fully sound-proofed.

They will need to be quiet. Often, rooms divided by a one-way mirror might not be fully sound-proofed.

![]() They should turn off their cell-phones. Answering calls will disturb other observers and sometimes the signal from a cell-phone can interfere with the recording equipment. It can be difficult to get busy people (especially executives) to turn off their phones; but if they understand that the signal can interfere with the equipment, they will usually oblige.

They should turn off their cell-phones. Answering calls will disturb other observers and sometimes the signal from a cell-phone can interfere with the recording equipment. It can be difficult to get busy people (especially executives) to turn off their phones; but if they understand that the signal can interfere with the equipment, they will usually oblige.

It is not good practice to allow participants’ managers to observe the session. This request is most often made when we are conducting activities with customers because the managers want to see for themselves what their employees are contributing to the product’s design. If participants know or believe that their boss is watching, it can dramatically impact what they do or say. For example, in a group task analysis, if participants know they are being watched by their boss, they may say that they do things according to what company policy dictates but this may not be the truth. You need to capture the truth. It is great to have customers interested in your activity, but explain to them that their presence may intimidate the participant, and that you will summarize the data for them (without specific participant names) as well as discuss the details after the session. We find that with this explanation they are typically understanding and accept your request not to observe. If you are unable to avoid this situation for political reasons (e.g., a high-profile customer that insists on observing), you may have to allow the supervisor to observe and then scrap the data. For ethical reasons you will also want to let the participant know he/she is being observed by the supervisor.

Introducing Your Think-aloud Protocol

A think-aloud protocol is the process of having participants speak what they are thinking as they complete a task. They tell you about the steps in the task as they complete them, as well as their expectations and evaluation statements. This technique is typically used for usability tests, but it can also be quite beneficial for certain user requirements activities where you are working with one person at a time – for example, individual card sorts (refer to chapter 10, page 414) and field studies (refer to chapter 13, page 562).

You get an understanding of why the user is taking the actions that he/she takes, and the person’s reactions to and thoughts about what he/she is working with. For example, in the case of a card sort, you can learn about why the person groups certain cards together and why he or she thinks certain cards do not belong.

Before asking participants to think-aloud, it can help to provide an example. It is best to use an example that reflects what they will be working with. If they will be completing tasks on the web, say, demonstrate an example with a web-based task. We often use the example of trying to find a blender on an e-commerce website. If the participant will be working with a physical product, then demonstrate the think-aloud protocol with a physical object (e.g., a stapler). Remember that the instructions to the participant should model what you want them to do. So if you want them to describe expectations, model that for them. If you want them to express feelings, model that for them. During the demonstration, the facilitator works through the task and the participant observes him/her using the protocol. Below is an example of a think-aloud protocol demonstration using a stapler (Dumas & Redish 1999):

“Now as you work on the tasks, I am going to have you do what we call ‘think out loud.’ What that means is that I want you to say out loud what you are thinking as you work. Let me show you what I mean. I am going to think out loud as I see whether I need to replace the staples in this stapler. ‘OK, I am picking it up. It looks like an ordinary stapler. I would expect that there would be some words or arrows that show me how it opens. I don’t see any here. I am disappointed in that. Well I am going to pull it apart here. I think that this is how it opens. It seems easy to pull apart, that’s good. I can see there are staples in it. So I am going to close it. That was pretty much how I expected the stapler to work.’

Do you see what I mean about thinking out loud? I am going to give you some practice by telling me out loud how you would replace the tape in this tape dispenser.”

We don’t generally comment on the specifics of what they say. It is almost always just a play-by-play of steps. But we do listen to the loudness of the participant’s voice. Many participants talk quietly as if it were a private conversation instead of a recorded session. If they are quiet, we say, “That was just what I want you to do, but remember you are speaking to the microphone, not just to me. You may have to talk a bit louder. Don’t worry, I will remind you if I can’t hear you.”

Moderating Your Activity

Excellent moderation is key to the success of any activity. Even when participants are provided with instructions, they do not always know exactly what you are looking for, so it is your job to remind them. Also, many of these activities are in the evening and people are tired after work – it will be your job to keep them energized. A moderator must keep the participants focused, keep things moving, make sure everyone participates equally, and ultimately ensure that meaningful data are collected.

When people think of moderation they might think of managing a group of people. Moderation of a group is the most complex, but moderation is also important for individual activities. There are a few rules that apply to both types, such as staying focused and keeping the activity moving. Some common individual and group moderating scenarios are discussed below. If you would like to take a class in moderating skills, or you are interested in having an outsider moderate the activity for you, Appendices B (page 688) and D (page 698) have some pointers.

Have personality

The participants should feel at ease around you, the moderator. Be personable and approachable. Also, remember to smile and look them in the eyes. You may be tired and have had a terrible day, but you cannot let it show. You need to emanate a happy and positive attitude. Before the session begins, while people are coming in or eating dinner, chat with them. You do not need to talk about the activity, but participants often have questions about your job, the product, or the activity. Getting to know the participants will help you get a sense for the type of people in the room, and it will get them comfortable speaking to you.

Ask questions

Remember that you are not the expert in the session, the participants are, and you should make them aware of that fact. Let them know that you will be stopping to ask questions and get clarification from time to time. The participants will undoubtedly use acronyms and terminology with which you are not familiar, so you should stop them and ask for an explanation rather than pushing on. There is no point collecting data that you do not understand.

You also want to make sure that you capture what the user is really saying. Sometimes the best way to ensure that you understand someone is to listen reflectively (“active listening”). This involves paraphrasing what the participant has said in a non-judgmental, non-evaluative way, and then giving the participant a chance to correct you if necessary.

At other times, you will need to probe deeper and ask follow-up questions. For example, Joe may say “I would never research travel on the web.” If you probe further and ask “Why?” you may find out that it is not because Joe thinks it would be a bad idea to research travel on the web; it’s just that he never conducts travel research because he spends all of his vacation time at his condo in the Florida Keys.

Stay focused

Do not let participants go off on a tangent. Remember that you have a limited amount of time to collect all of the information that you need, so make sure that participants stay focused on the topic at hand. Small diversions, if relevant, are appropriate, but try to get back on track quickly. You can make comments such as “That is really interesting, but perhaps we can delve into that more at the end of the session, if we have time.”

Another strategy is to visually post information that will help keep people on track. For example, if you are running a group task analysis, write the task in the top of the task flow. If people get off topic, literally point back to the task that is written down and let them know that, although their comments are valuable, they are beyond the scope of the session. If you are running a focus group or a wants and needs analysis, do the same by visually displaying the question via a projector or on a flip chart. You can also periodically repeat the question to remind people what the focus of the discussion is.

You are not a participant

Remember that you are the moderator! It is critical that you do not put words into your participants’ mouths. Let them answer the questions and do not try to answer for them. Also, do not offer your opinions because that could bias their responses. This may sound obvious, but sometimes the temptation can be very hard to resist. We have seen this most frequently in group task analyses where participants are working together to create a task flow. As a moderator, your hands should be empty. You do not want to write anything or touch any of the cards. If the participants see that you are doing the work, they will often be happy to allow you to take over. If you fall into this trap, at the end of the session you will end up with a flow that represents your thinking instead of that of the end users.

Keep the activity moving

Often, people stay focused on the goal or question presented in the activity, but they go into far more detail than necessary. You need to control this, otherwise you might never finish the activity. It is OK to say to them: “I think I now have a good sense of this topic, so let’s move on to the next topic because we have a lot of material to get through today.” After making a statement such as this once or twice during the session, people will typically get a sense of the level of detail you are going after. You can also let them know this up-front in your introduction: “We have a lot to cover today, so I may move along to the next topic in the interests of time.”

Keep the participants motivated and encouraged

On average, a user requirements activity lasts for about two hours. This is quite a long period of time for a person or a group of people to be focused on a single activity. You must keep people engaged and interested. Provide words of encouragement as often as possible. Let them know what a great job they are doing and how much their input is going to help your product. A little acknowledgment goes a long way. Also keep an eye on your participants’ energy levels. If they seem to be fading, you might want to offer them a break or offer up some of those left-over cookies to help give them the necessary energy boost. You want everyone to have a good time, and to leave the activity viewing it as a positive experience. Try to be relaxed, smile often, and have a good time. Your mood will be contagious.

No critiquing

As the moderator, you should never challenge what participants have to say. This is crucial, since you are there to learn what they think. You may completely disagree with their thoughts, but you are conducting an end user activity and you are not the end user in this situation. You may want to probe further to find out why a participant feels a certain way; but at the end of the day, remember that, in this session, he or she is the expert; not you. Collect these thoughts and ideas and you can validate them later, if necessary.

At the beginning of a session, stress that there is to be no critiquing of input. Also, emphasize to the participants that this is not an evaluation. All ideas are correct and you welcome all their thoughts and comments. Inevitably, someone cannot resist critiquing another person’s ideas. Be sure to post this as a rule to help remind your participants. Let them know that it is OK to have different ideas, but there are no wrong ideas. Usually if you remind people of this, they will let everyone have their say.

Everyone should participate

In a group activity, it can take a great deal of energy to draw out the quiet members, but it is important to do so. If you have a focus group of ten people and only five are contributing, that essentially cuts your effective participant size in half. You must get everyone involved and the sooner you do this the better. Call quiet members out by name and ask them their thoughts: “Jane, what do you usually do next?” If things don’t improve you could try moving towards a round-robin format (i.e., everyone participates in turn). This can be an effective solution for group activities like a focus group; however, it is not ideal for every activity (e.g., a group task analysis). If you start off doing a round-robin, you may not need to continue it for the whole activity; just a couple of turns may help people feel more comfortable about speaking up.

No one should dominate

It is very easy for an overbearing participant to dominate the group and spoil the group dynamic. It can take a great deal of skill and tact to rein in a dominating member without embarrassing him/her. When you notice that a participant is beginning to dominate, call on others in the group to balance things out. If you are standing in the middle of the group (e.g., in a U-shaped table formation), use body language to quieten down the dominant user. Turn your body so that the dominant one cannot get your attention, focus fully on a quieter participant, and avoid eye contact. If things do not improve, gently thank the overbearing person for earlier ideas and let him/her know that now other participants need to contribute. If it is clear that the participant will not work with others, give the group a break. Take the strong-willed member to the side and remind him/her that this is a group activity and that everyone should participate equally. You can tell the person that he or she might be asked to leave. Alternatively, you can provide the user with his/her incentive with thanks and provide a graceful exit. It is certainly the exception rather than the rule that things get this bad, but it is good to have a plan of action in mind in case they do.

Another technique that works well in group sessions is to ask for participants to raise a hand before speaking, and to have an assistant note any hand that goes up and make sure that person gets called on eventually. By forcing participants to wait until they are called on, you have a means to eliminate interruptions. This is particularly effective when the group size is over ten. All the participant has to do is raise a hand briefly, which is noted, and then they will be called on as soon as there is a break in the action. Ideally, you do not want to have to resort to this; but if overbearing participants cannot control themselves, you will have to resort to a more structured session.

Practice makes perfect

Moderating activities is definitely an art. The bottom line is that it takes practice and lots of it! We still find that we learn new tricks and tips and also face new challenges with each session.

We recommend that people new to moderating groups watch videotapes of the activity they will be conducting and observe how the facilitator interacts with the participants. Next, they should shadow a facilitator. Being in the room as the activity is going on is a very different experience from watching a video. Also, a beginner should practice with co-workers who are experienced moderators. Set up a pilot session so that you can practice your moderating skills before the real activity. Have your co-workers role-play. For example, one person can be the dominant participant, one can be the quiet participant, one can be the participant who does not follow instructions, etc. You can videotape the sessions and watch them with an experienced moderator to find out how you can improve. Another great idea is to be a participant in focus groups. Find a local facility that runs and/or recruits for them and contact them to get on their participant list. That way you can observe professional moderators at work.

Having said that, you must find your own style. For example, some people can easily joke with participants and use humor to control the overbearing ones: “If you don’t play well with the others, I will have to take your pen away!” Other people are not as comfortable speaking in front of groups and have difficulty using humor in these situations. In those cases, trying to use humor can backfire and might come across as sarcasm. Find an experienced moderator to emulate – one whose personality and interaction style are similar to yours.

Recording and Note-taking

There are a few options when deciding how to capture information during your activity.

Take Notes

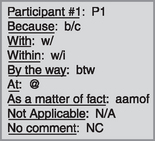

Taking notes on a clipboard is one obvious choice. One of the benefits of taking notes during the session is that you can walk away from the activity with immediate data and you can begin analysis (see Figure 6.2 for a sample of notes). You are also signaling to the participants that you are noting what is being said. It is good to show the participants that you are engaged in the activity, but they might be offended if you are not taking notes when the participants feel they are saying something particularly noteworthy.

A potential problem with taking notes is that you can get so wrapped up in being a stenographer that you have difficulty engaging the participants or following up. You could also fail to capture important comments because the pace of a discussion can be faster than your note-taking speed. If you choose to take notes yourself during a session, develop shorthand so that you can note key elements quickly (see Figure 6.3 for some sample shorthand). Also, do not try to capture every comment verbatim – paraphrasing is faster.

For some activities, such as focus groups and group task analyses, the moderating is so consuming that it is simply not possible for you to take effective notes. Then, a better option is to have a co-worker take notes for you. If appropriate, you might wish to take some high-level notes yourself to highlight key findings, but leave all the details for a co-worker to capture.

As mentioned, the great benefit of notes is that you have an immediate record to begin data analysis. The note-taker can be in the same room with you or behind the one-way mirror if you have a formal lab set up (refer to chapter 4, Setting up Facilities for Your User Requirements Activity, “Building a Permanent Facility” section, page 111). It can also help to have an additional pair of eyes to discuss the data with and come up with insights that you might not have had yourself.

If the note-taker is in the same room, you may or may not want to allow the person to pause the session if getting behind in the notes or not understanding what a participant has said. This can be very disrupting to the session, so ideally you want an experienced note-taker. The person should not attempt to play court stenographer: you are not looking for a word-by-word account, only the key points or quotes. The moderator should keep the note-taker in mind and ask participants to speak more clearly or slowly if the pace becomes too fast.

Use Video or Audio Recording

The benefit with recording is that you do not have to take notes, so you can focus solely on following up on what the participants say. The recordings capture nuances in speech that you could never capture when taking notes. Video recording also has the benefit of showing you the participants (as well as your own) body language. You can also refer back to the recording as often as needed. Some tools today can even analyze multimedia files (see Appendix G, page 722).

If you choose to rely solely on video or audio recording and not to take notes during the session, you will either have to listen to the recording and make notes, or send the recording out for transcription. Transcription is expensive and it takes time (it is charged per hour of transcription, not per hour of recording). Depending on the complexity of the material, the number of speakers, and the quality of the recording, it can take four to six times the duration of the recording to transcribe. In the San Francisco Bay area in 2004, a professional transcription company charged about $42 per hour of transcription – so the cost to transcribe a single two-hour interview can run between $168 and $252. Searching the phone book, you may be able to find individuals who transcribe “on the side” and charge significantly less than professional companies.

Getting tapes transcribed is not the same thing as taking notes during the session. Shorthand notes pull out the important pieces of information and leave behind all the noise. If you get transcripts you will need to read through them and summarize. We recommend getting transcripts of the session only when you need a record of who said what (e.g., for exact quotes or documentation purposes). Regulated industries (e.g., FDA) may also require such documentation.

Finally, you should be aware that recording the session can make some participants uncomfortable, so they may not be forthcoming with information. Let the participants know when you recruit them that you plan to record. If a person feels uncomfortable, stress his or her rights, including the right to confidentiality. If the person still does not feel comfortable, then you should consider recruiting someone else or just relying on taking notes. In our experience, this outcome is the exception rather than the rule.

Combine Video/Audio and Note-taking

As with most things, a combination is usually the best solution. Having a co-worker take notes for you during the session while it is being recorded is the optimal solution. That way you will have the bulk of the findings, but if you need clarification on any of the notes or user quotes, you can refer back to the recording. This is often necessary for group activities. Because so many people are speaking during a group activity, and because conversations can move quickly, it can be difficult for a note-taker to capture every last detail. An audio- or videotape of the session is extremely important for later review. It will allow you to go back and get clarification in areas where the notes may not be clear or where the note-taker may have fallen behind. In addition, although it is rare, recordings do fail and your notes are an essential back-up.

Dealing with Awkward Situations

Just when you think you’ve seen it all, a participant behaves in a way you could never have expected! The best way to handle an awkward situation is by preventing it all together. However, even the best-laid plans can fail. What do you do when a user throws you a curve ball? If you are standing in front of a group of 12 users and there is a room of eight developers watching you intently, you may not make the most rational decision. You must decide before the situation ever takes place, how you should behave to protect the user, your company, and your data. Refer to chapter 3, Legal and Ethical Considerations, page 94, to gain an understanding of these issues.

In this section we look at a series of several uncomfortable situations and suggest how to respond in a way that is ethical and legal, and which preserves the integrity of your data. Unfortunately, over the last several years we have encountered almost every single one of these awkward situations. They have been divided by the source of the issue (i.e., participant or product team/observer). We invite you to learn from our painful experiences. There are also some awkward situations that relate to late participants. These situations are discussed in the “Dealing with Late and Absent Participants” above.

Participant Issues

The Participant is Called Away in the Middle of the Test

Situation: You are half way through interviewing a participant when her cell-phone rings. She answers it and says it’s her child calling. She states that she must go but will be back in 45 minutes to finish the interview. What do you do?

Response: Thank her for her time, pay her, and let her know that it will not be necessary for her to return. It is not ethical to withdraw compensation if the participant leaves early. To force her to stay is not only unethical but the participant would clearly be distracted during the remaining questions. A participant is free to leave without penalty at any point, so remember to compensate her for her expertise and effort. It would be impossible to allow her to return in the case of a group activity as she would have missed too much of the session. In the case of an individual activity it would be possible to allow her to return, but the 45-minute delay between questions would differentiate her data from that of other participants.

To prevent this from happening, it is always a good idea to ask participants to turn off their cell-phones and pagers before the activity begins. If the participant states she is expecting an important call and cannot turn off the phone, do not press the issue further because it may only serve to distract or upset the participant. Be prepared in the future by over-recruiting so that the loss of one or two participants does not affect the integrity of the dataset.

The Participant’s Cell-phone Rings Continuously

Situation: The participant is a very busy person (e.g., doctor, database administrator). She is on call today and cannot turn off her cell-phone for fear of losing her job. You reluctantly agree to let her leave the phone on. Throughout the session, her pager and phone buzz, interrupting the activity. Each call lasts only a couple of minutes but it is clear that the participant is distracted. This user type is really hard to come by so you hate to lose her data. Should you allow the activity to continue, or ask her to leave?

Response: It is obvious that the user is distracted and it won’t get better as the session continues. If this is an individual activity, you may choose to be patient and continue. However, if this is a group session where the user is clearly disturbing others, have a collaborator follow the participant out during the next call. When she finishes her call, ask her to turn the phone and pager off because it is causing too much distraction. If this is not possible, offer to allow her to leave now and be paid, since it seems to be a very busy day for her. In our focus group with doctors, one of the participants spent more time in the hallway on his cell-phone than in his chair. The other participants were clearly annoyed and distracted. When given the choice to turn his phone off or leave, he surprisingly chose the former. Unfortunately, his mind wasn’t on the discussion and he didn’t participate in the rest of the session.

If you know your user type is in a highly demanding job, you should inform potential participants during the screening process that they will have to turn their cellphones and pagers off for the duration of the activity (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 161). If the potential participant will be on duty the day of the session and cannot comply with the request, do not recruit him/her. Otherwise you are inviting trouble. When the participants arrive for the activity, ask everyone to turn their cellphones and pagers off. They agreed to give you one or two hours of their time and you are compensating them for it. It is not unreasonable to insist they give you their full attention, especially if you made this request clear during the screening process.

The Wrong Participant is Recruited

Situation: During an activity, either it becomes painfully obvious or the user lets it slip that he does not match the user profile. The participant has significantly less experience than he originally indicated, or does not match the domain of interest (e.g., has the wrong job to know about anything being discussed). It is not clear whether he was intentionally deceitful about his qualifications or misunderstood the requirements in the initial phone screener. Should you continue with the activity?

Response: Is the participant different on a key characteristic? If you and the team agree that the participant is close enough to the user profile to keep, continue with the activity and note the difference in the report.

If the participant is too different, your response depends on the activity. If it is a group activity where the participants do not interact with one another (e.g., a group card sort), note the participant and be sure to throw his data out. If it is a group activity that involves interaction among the participants, you will have to remove the participant from the session. The fact that the person is a different user type could derail your session entirely. Take the participant aside (you do not want to embarrass him/her in front of the group) and explain that there has been a mistake and apologize for any inconvenience you may have caused. Be sure to pay the participant in full for his effort.

If it is an individual activity, you may wish to allow the participant to continue with the activity to save face, and then terminate the session early. It may be necessary to stop the activity on the spot if it is clear the participant simply does not have the knowledge to participate and to continue the activity would only embarrass the participant further. Again, pay the participant in full; he or she should not be penalized for a recruiting error.

If the participant turns out to work for a competitor, is a consultant who has worked for a competitor and is likely to return to that competitor, or is a member of the press, you need to terminate the session immediately. Remind the person of the binding confidentiality agreement, pay him, and escort him out. Put him on the watch list immediately (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Create a Watch List” section, page 190).

Follow up with the recruiter to find out why this participant was recruited (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Recruitment Methods” section, page 173). Review the remaining participant profiles with the team/recruiting agency to make sure that no more surprises slip in. Make sure the recruiter clearly understands the user profile before proceeding to recruit any others. To better prepare for any usability activity, create the user profile and screener with the development team. In addition, review and approve each user with the team as he or she is recruited.

A participant thinks he is on a job interview

Situation: The participant arrives in a suit and brings his resumé, thinking he is being interviewed for employment at your company. He is very nervous and asks about available jobs. He says that he would like to come back on a regular basis to help your company evaluate its products. He even makes reference to the fact that he needs the money and is grateful for this opportunity to show his skills.

Response: This situation can be avoided by clarifying up-front when the participant is recruited that this is not a job interview opportunity, and in no way constitutes an offer of employment (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 161). If the participant attempts to provide a resumé at any point in the conversation, stop the activity and make it clear that you cannot and will not accept it. It is best not to even agree to forward a resumé to the appropriate individual. The participant may incorrectly assume that your agreement to forward it comes with your recommendation. You may then receive follow-up phone calls or e-mails from the participant “to touch base about any job opportunities.” When the economy is tough, you will likely encounter this situation more than once.

Given that the participant is already in your activity, you need to be careful not to take advantage of a person who is obviously highly motivated but for the wrong reasons. In this case, the activity should be paused and you should apologize for any misunderstanding, but make it clear that this is not a job interview. Reiterate the purpose of the activity and clarify that there is no follow-on opportunity for getting a job at your company which can be derived from his participation. The participant should be asked whether he would like to continue now that the situation has been clarified. If not, the participant should be paid and leave with no further data collection.

A Participant Refuses to be Videotaped

Situation: During recruiting and the pre-test instructions, you inform the participant that the session will be videotaped so that you can go back to pick up any comments you may have missed. The participant is not happy with this. She insists that she does not want to be videotaped. You assure her that her information will be kept strictly confidential but she is not satisfied. Offering to turn the videotape off is also not sufficient for the participant. She states that she cannot be sure that you are not still taping her and asks to leave. Should you continue to persuade her? Since she has not answered any of your questions, should you still pay her?

Response: Although this rarely occurs, you should not be surprised by it. It is unethical to coerce the participant to stay. You may want to ask if she would be willing to be audiotaped instead. This is not ideal but at least you can still capture her comments. If she still balks, tell her that you are sorry she does not wish to continue but that you understand her discomfort. You should still pay the participant. If you have a list of participants to avoid, add her name to this list (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Create a Watch List” section, page 190). Alternatively, if the participant agrees to stay, if the user type is difficult to find, and/or if you are dealing with a customer, you may wish to rely on notes and not worry about the video or audio recording.

To avoid such a situation in the future, inform all participants during the phone screening that they will be audio- and/or videotaped and must sign a confidentiality agreement (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 161). Will this be a problem? If they say that it is, they should not be brought in for any activity.

A Participant is Confrontational With Other Participants

Situation: While conducting a group session, one of the participants becomes more aggressive as time goes by. He moves from disagreeing with other participants to telling them their ideas are “ridiculous.” Your repeated references to the rule “Everyone is right – do not criticize yourself or others” is not helping. Unfortunately, the participant’s attitude is rubbing off on other group members and they are now criticizing each other. Should you continue the session? How do you bring the session back on track? Should you remove the aggressive participant?

Response: Take a break at the earliest opportunity to give everyone a chance to chat and cool off. Since you are the focus of most participants at this moment, you will need a co-worker to assist you. Have the co-worker quietly take the participant outside of the room and away from others, to dismiss him. The co-worker should tell the participant that he has provided a lot of valuable feedback, thank him for his time, and pay him. Alternatively, you may wish to tell him the real reason he is being asked to leave, thereby emphasizing your commitment to fostering acceptance and non-judgmental behavior. We typically do not take this approach because things may get confrontational and you will then need to devote time and energy to this confrontation. When you restart the session, if anyone notices the absence of the participant, simply tell the group that he had to leave early. It is never easy to ask a participant to leave, but it is important not only to salvage the rest of your data but also to protect the remaining participants in your session.

A Participant Takes Over the Group

Situation: At the beginning of a group task analysis, a user decides to “lead” the group and begins developing the entire flow himself. You have stopped him once and let the entire group know that they must work together to develop the flow. In addition, you have encouraged the other group members to get involved and asked specific members their thoughts on the flow so far. Unfortunately, the overbearing participant seems undeterred by this brief interruption and continues to dominate the group. How do you give control back to the group? Should you allow the participant to stay?

Response: Take a break and have a co-worker take the participant outside the room. You have a couple of options here. The collaborator can give him his own set of materials (make sure you have an extra set made) and allow him to work on his own. Alternatively, the collaborator can thank the participant for all of his input, provide his incentive, and escort him out. Whatever the solution, the participant should leave happy and never feel scolded or humiliated in front of the other participants.

After the break, inform the participants that the absent participant left early. You should then undo any of the work the assertive participant has done alone and ask the remaining participants to continue.

It is important to be an assertive, but not overbearing, moderator during these difficult sessions. You must draw out the reserved participants and quiet down the aggressive participants so it does not get to this point. It is common for some people to assume that every group “needs a leader” and nominate himself or herself. We have noticed that highly trained or technical users tend to have more dominating personalities. If you will be conducting a group activity with highly skilled users, beef up your moderations skills by practicing with your colleagues (see “Moderating Your Activity” on page 220). Consider having a co-worker assist you, since two people correcting the overbearing participant may be more effective.

A Participant is Not Truthful About Her Identity

Situation: You recognize a participant from another activity you conducted but the name doesn’t sound familiar. You mention to her that she looks familiar and ask whether she has participated in another study at your company. She denies that she has ever been there before, but you are convinced she has. Should you proceed with the test or pursue it further?

Response: Ask every participant for ID when you greet them. If a participant arrives without some form of ID, apologize for the inconvenience and state that you cannot release the incentives without identification. If it is possible, reschedule the activity and ask the participant to bring ID next time.

When recruiting, you should inform participants that you will need to see an ID for tax purposes, as well as for security purposes (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 161). In the US, the Internal Revenue Service requires that companies complete a 1099 form for any individual who receives more than $600 from you in a year. For this reason, you need to closely track whom you compensate throughout the year. During recruitment, you may say to participants:

“In appreciation for your time and assistance, we are offering $100 in American Express gift checks. For tax purposes, we track the amount paid to participants and so we will be asking for ID. We also require ID when issuing a visitor’s badge. If you can simply bring your driver’s license with you, we will ask you to present it upon arrival.”

Repeat this in the phone or e-mail confirmation you provide to participants. For participants being dishonest about their identity (in order to participate in multiple studies and make additional money), this will dissuade them from following through. You will probably get a call back from the participant saying that he or she is no longer available. For honest participants, it reminds them to bring their license with them, as opposed to leaving it in the car or at home.

If the information provided does not match the information on the driver’s license, you will have to turn the participant away. Then, copy the information from the ID next to the “alternative” information provided by the participant. Place both identities on your Watch List (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Create a Watch List” section, page 190).

A Participant Refuses to Sign Confidential Disclosure Agreement and Consent Forms

Situation: You present the usual confidential disclosure agreement (CDA) and consent form to the user and explain what each form means. You also offer to provide copies of the forms for the participant’s records. The participant glances over the forms but does not feel comfortable with them, particularly the CDA. Without a lawyer, the participant refuses to sign these documents. You explain that the consent form is simply a letter stating the participant’s rights. The CDA, you state, is to protect the company since the information that may be revealed during the session has not yet been released to the public. Despite your explanations, the participant will not sign the documents. Should you continue with the activity?

Response: Absolutely not. To protect yourself and your company, explain to the participant that, without her signature, you cannot conduct the activity. Since the participant is free to withdraw at any point in time without penalty, you are still required to provide the incentive. Apologize for the inconvenience and escort her out. Be sure to place her on your Watch List (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Create a Watch List” section, page 190).

Prevent this situation by informing participants during recruitment that they will be expected to sign a confidentiality agreement and consent form (refer to chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 161). Offer to fax participants a copy of the forms for them to review in advance. Some participants (particularly VPs and above) cannot sign CDAs. Their company may have a standard CDA that they are allowed to sign and bring with them. In that case, ask the participant to fax you a copy of their CDA and then forward it to your legal department for approval in advance.

If the legal department approves of their CDA, you may proceed. However, if a participant states during the phone interview that he/she cannot sign any CDA, thank the person for his/her time but state that the person is not eligible for participation.

Fire Alarm Sounds in the Middle of a Test

Situation: While in the middle of a test, a fire alarm sounds. It is a false alarm but the participant still seems unnerved. After evacuating the building, the participant states he would like to continue with the activity, but you are not sure whether the alarm disturbed the participant such that he will not be able to concentrate. Should you let the activity continue? If so, do you use the data?

Response: After security allows you to return, take a break and offer the participant something to drink. Let him know that he provided a lot of valuable feedback, that he is not obligated to stay, and that he will be paid in full regardless. If the participant seems more at ease and is still eager to continue, allow him to proceed. Compare his data to the other participants to determine whether he is an outlier.

Product Team/Observer Issues

The Team Changes the Product Mid-test

Situation: You are conducting a focus group for a product that is in the initial prototype stage. The team is updating the code while the focus groups are being conducted. In the middle of the second focus group, you discover the team has incorporated some changes to the product based on comments from the previous focus group. Should you continue the focus groups with the updated product, or cancel the current focus group and bring in replacements so that all users see the same product? How do you approach the team with the problem?

Response: Ask the participants to take a break at the least disruptive opportunity and go to speak with the developers in attendance while your co-moderator attends to the group. This will give you time to determine whether the previous version is still accessible. If it is, use it. If the previous version is not available, it is up to you whether you would like to get some feedback on the new version of the prototype, or you might attempt to continue the focus group with activities that do not rely on the prototype. Be sure to document the change in the final report. Meet with the team as soon as possible to discuss the change in the prototype. Make sure the team understands that this may compromise the results of the activity. If they would like to do an interactive design approach, they should discuss this with you in advance so that you may design the activity appropriately.

As a rule, make sure that you inform product teams of “the rules” before any activity. In this case, before the activity you would inform them that the prototype must stay the same for all focus group sessions. Be sure to inform them “why” so that they will understand the importance of your request. Let them know that you want to make design changes based on what both groups have to say, not just one. Remember that this is the product team’s session too. You can advise them and tell them the consequences, but be aware that they may want to change it anyway and it is your job to analyze and present the results appropriately (even if this means telling stakeholders that the data are limited because of a decision the team made).

In some cases, the team finds something that is obviously wrong in the prototype and changes it after the first session. Often this is OK. But they should discuss it with you prior to the session. If they don’t discuss it with you and you find out during the session, it doesn’t always invalidate the data if it is something that should be changed in any case. When working with a team you must strike a balance between being firm but flexible.

An Observer Turns on a Light in the Control Room During Your Activity

Situation: You are interviewing a participant in the user room while the team is watching in the control room. During the interview, one of the team members decides to turn on a light because he is having trouble seeing. The control room is now fully illuminated and the participant can see there are five people in the other room watching intently. Should you try to ignore the people in the other room and hope it does not draw more attention to the situation, or should you stop the interview and turn off the light?

Response: The participant should never be surprised to learn that people are in the control room observing the activity. At the beginning of every activity, participants must be made aware that “members of our staff sometimes observe in the other room.” It is not necessary to state the specific number of people in the other room or their affiliation (e.g., usability group, development team). Participants should also be warned that they may hear a few noises in the other room, such as coughing or a door closing but they should just ignore it. Their attention should be focused on the activity at hand. Some people like to show the participant the control room and the observers prior to the session. We typically do not adopt this approach because participants can become intimidated if they know that a large group of people are observing.

In the situation above, if the participant is not facing the other room and has not noticed the observers, do not call attention to it (someone may turn the light off quickly). This actually happened to one of our co-workers. Thanks to a datalogger with Ninja-like speed, the lights were turned off before the participant even noticed. However, if the participant has seen the observers, simply ask the observers to turn off the light and apologize to the participant for the disruption. After the participant has left, remind the team how one-way mirrors work and explain that it may affect the results if the participants see a room full of people watching them. Participants may be more self-conscious about what they say and may not be honest in their responses. If you notice that the participant’s responses and behavior change dramatically after seeing the observers, you may have to consider throwing away the data.

Product Team/Observers Talk Loudly During an Activity

Situation: While interviewing a participant in the user room, the team in the control room begins talking. As time goes by, the talking grows louder and the team begins laughing. The participant appears to be ignoring it, but the noise is easily audible to you so the participant must be able to hear it too. In addition, the datalogger is having difficulty hearing what the participant is saying and fears the participant can hear the conversation. Should you or the datalogger interrupt the interview to ask the team to be quiet and possibly draw more attention to it, or should you continue to ignore the noise?

Response: This situation can be avoided if you ask the developers to maintain quiet before you leave the control room to conduct the interview (see “Inviting Observers,” page 216). You must clearly explain to the observers that the room is not completely sound-proof and that silence is extremely important during an activity. If this is unsuccessful, act quickly. Having another member of your team in the control room (usually a datalogger) is also helpful because that individual can prevent the situation from getting out of hand. Hopefully, your datalogger will tell them to quiet down and remind them that the room is not sound-proof. However, if the volume increases enough for you to become aware of it, excuse yourself to “get something in other room” (e.g., another pen, your drink, the participant’s compensation). When you step into the other room, inform the observers that you can hear them. Politely tell them that the interview can be very revealing so they probably want to pay close attention. If there is an important conversation that they must have, they should excuse themselves and speak in another office or lobby – but not out in the hallway because the user may be able to hear them there too.

If there are multiple sessions, observers may think that they have heard it all after the first participant. As a result, they start talking and ignoring the session. Explain to them that every participant’s feedback is important and that they should be taking note of where things are consistent and where they differ. Be nice but firm. You are in charge. Observers are rarely uncooperative.

We had the unfortunate situation once when a participant actually said “I can hear you laughing at me.” Despite assurances that this was not the case, the participant was devastated and barely spoke a word for the rest of the session. Amazingly, the observers in attendance were so caught up in their own conversation that they did not hear what the participant said!

Pulling It All Together

In this chapter, we have given you ingredients that will help you conduct any of your user requirements activities effectively. You should now be able to deal with participant arrivals, get your participants thinking creatively, moderate any individual or group activity, and instruct your participants how to think aloud. In addition, we hope that you have learned from our experiences and that you are prepared to handle any awkward testing situation that may arise. In the following chapters we delve into the methods of a variety of user requirements activities.