FIELD STUDIES

WHEN SHOULD YOU CONDUCT FIELD STUDIES?

THINGS TO BE AWARE OF WHEN CONDUCTING FIELD RESEARCH

FIELD STUDY METHODS TO CHOOSE FROM

Introduction

Collecting data in the field (i.e., in your user’s environment) is sometimes referred to as “site visits.” However, “site visit” is a broad term and can include other interactions with customers while not necessarily collecting data (e.g., conducting a sales demo). More accurate names for site visits to collect data are “ethnographic study,” “field research,” or “field studies.”

“Field studies” refers to a broad range of data gathering techniques at the user’s location – including observation, apprenticeship, and interviewing. A field study can be composed of several visits to the user’s environment and can be conducted in any environment in which a user lives or works. For example, researchers observed users in a vineyard to develop a ubiquitous computing system for agricultural environments (Brooke & Burrell 2003). Studies have also been done in people’s homes and offices. Field studies can last for a couple hours to a full day or even weeks, depending on the goals and resources of the study. The advantage of this technique is that you get to observe the users completing the tasks in their environment. You can observe their task flows, inefficiencies, and challenges directly. This information can then be used to help you understand the user requirements for your product.

You will notice that this chapter is designed a little differently from the other method-related chapters. In the previous chapters, we presented one primary way to conduct a specific method and then a few modifications. There is no one best way to conduct a field study – it depends on the goals of your study and your access to users. Consequently, we will provide you with several variations from which to choose. In this chapter, we discuss different types of field studies available to enable you to go into your user’s environment to collect data, how to select the best method to answer your questions, special considerations, how to analyze the data you collect, and how to present the results to stakeholders. Additional sources for information are provided throughout, as well as lessons learned. Finally, a case study by Bentley College (for Staples) is showcased to demonstrate the value of a field study in the real world.

When Should You Conduct Field Studies?

The purpose of a field study is to understand the end user’s natural behavior in the context of his or her everyday environment. You will want to conduct a field study any time you are interested in seeing first-hand how the user works or behaves, the context of the tasks undertaken, and the artifacts used to support those tasks (e.g., checklists, forms to fill out, calendars). It can be more advantageous to observe user behavior than to ask the user to describe how he/she works because of issues with memory, social desirability, acquiescence, and prestige response bias. In addition, users often know more than they say in a single or even several interviews. It is not that they are “holding out” on you, rather that much of what they do has become automatic and, as a result, is difficult to articulate. For example, describe how you balance yourself while riding a bicycle. It’s not easy to describe, is it? Alternatively, users may incorrectly explain a behavior because they don’t understand it well enough.

You can conduct a field study to learn about an area in general (exploratory) or to answer a specific question or problem. You can also conduct a longitudinal study (i.e., a series of visits with the same participant over time) rather than an “out-of-box” or one-time exposure study. Field studies can be used to accomplish a number of goals:

![]() When the product development team needs to be jolted out of their current way of thinking or to challenge/verify assumptions that you or the stakeholders have about users/tasks/environment

When the product development team needs to be jolted out of their current way of thinking or to challenge/verify assumptions that you or the stakeholders have about users/tasks/environment

![]() Identify a mismatch between the way user’s work/think and the tools/procedures they are forced to use

Identify a mismatch between the way user’s work/think and the tools/procedures they are forced to use

![]() Identify training materials needed

Identify training materials needed

![]() Collect artifacts (i.e., objects or items that users use to complete their tasks or that result from their tasks)

Collect artifacts (i.e., objects or items that users use to complete their tasks or that result from their tasks)

![]() Verify the user profile (are people using your product who do not match your initial user profile?)

Verify the user profile (are people using your product who do not match your initial user profile?)

![]() Develop personas through observations of actual users (refer to Chapter 2, Before You Choose an Activity, “Step 2: Personas” section, page 47)

Develop personas through observations of actual users (refer to Chapter 2, Before You Choose an Activity, “Step 2: Personas” section, page 47)

![]() Collect necessary information for another usability activity (e.g., develop a survey, identify tasks for a usability test).

Collect necessary information for another usability activity (e.g., develop a survey, identify tasks for a usability test).

Field studies are excellent for collecting rich, detailed data and for obtaining a holistic view of the process or domain. Field studies are not a good technique if you want to collect quantitative data or data from large samples. The data collected are usually qualitative and it is too expensive and time-consuming to examine large sample sizes. All in all, field studies allow you to collect data to design based on reality, not assumptions. The goal of a field study is to make the implicit aspects and processes of the user environment explicit.

Things To Be Aware of When Conducting Field Research

There are several challenges you may face when proposing a field study. There are also challenges you could face while conducting the study. Below are some issues to be aware of when deciding to conduct a field study.

Gaining Stakeholder Support

It can be difficult to convince people with limited time and budgets to support field studies. Products must be developed on tight budgets and deadlines. It can be easier to convince product teams or management to support a wants and needs session or focus group, because the materials needed are few and the time frame for delivering results is short. It can be much more difficult to get that same support for longer term, off-site studies with actual customers or end users.

The fact is, no short-term, lab-based study can compare to observing users in their own environment. And the reality is that schedules slip. Even if you cannot get the information in time to influence the upcoming release of the product, there will be future releases where your data can be used. You want your information to make an impact as soon as possible, but do not let schedules prevent you from collecting information altogether.

There are also discount ways to collect information. Write a detailed proposal to demonstrate the information you plan to collect and when. Also include estimated cost, and immediate and long-term benefits. You may also want to show documented cases where products went wrong and could have been saved by conducting a field study. Better understanding of your users can also provide a competitive edge.

Despite sharing the war stories listed by Hackos and Redish, your stakeholders may still offer an abundance of arguments against conducting field studies. Below are just a few you may hear:

“We simply don’t have the time or money for such a study.”

“Sales owns the customers. We don’t want to ruin any potential deals. We don’t want to make the customer unhappy by pointing out what our product doesn’t do. This will be too time-consuming for our customers.”

“You’ll make promises we can’t keep. You’ll let out confidential information.”

“We have information already. Why collect more?”

“We’re introducing a different process so don’t waste your time studying the current process.”

“This product/process/service is completely new. There is nothing to observe.”

“Everyone does it differently so there is no point studying a few users.”

“We’re changing just one part of the system/product/environment; we don’t need to study more than that.”

“We are developing this product for our own company, not for sale, so we don’t need a field study.”

In Chapter 1, we offer counter-arguments for each of these statements (refer to Chapter 1, Introduction to User Requirements, “Getting Stakeholder Buy-in for Your Activity” section, page 14). We strongly recommend reviewing these prior to presenting a proposal for a field study.

Finally, you will likely need to educate stakeholders on the empirical nature of usability, how the information you collect on-site with users differs from lab-based data, and how the data you collect in field studies can provide a competitive edge.

Other Things to Keep in Mind

Once you have convinced stakeholders, there are a few other things to keep in mind when designing and conducting field studies.

Types of bias

There are two types of bias to be aware of when conducting field studies. The first is introduced by the investigator and the second by the participant.

If the investigator is a novice to the domain, he or she may have a tendency to conceptually simplify the expert users’ problem-solving strategies while observing them. This is not done intentionally, of course, but the investigator does not have the complex mental model of the expert, so a simplification bias results. For example, if an investigator is studying database administrators and does not understand databases, he/she may think of a database as nothing more than a big spreadsheet and misinterpret (i.e., simplify) what the database administrator is explaining or demonstrating. It is important for you to be aware of this bias and ask users or a subject matter expert to review your notes/observations. They can identify areas where you have over-simplified or incorrectly captured information.

The other type of bias is called a translation bias. Expert users will attempt to translate their knowledge so that the investigator can understand it. The more experts translate, the more there is the potential for them to over-simplify and distort their knowledge/skills/etc. One way to avoid this is to ask the expert user to train you or speak to you as if you had just started the job. If you are missing the background knowledge necessary to understand everything the user is saying, you may either ask probing questions or bring a subject matter expert (SME) with you to “translate.” However, it is to your advantage to learn as much as you can prior to your visit so that you have some mental model to begin understanding what you are observing. You should be enthusiastic about learning the domain and become well-versed yourself, but with a “usability hat on” so that you can identify opportunities for improvement. This is different from coming in with preconceived notions. You should have a good base of knowledge but do not think about solutions yet.

The Hawthorne effect

Participants may behave differently when observed; this is known as the Hawthorne effect. They will likely be on their best behavior (e.g., observing standard operating procedures rather than using their usual shortcuts). It can take some time for users to feel comfortable with you and reveal their “true behavior.” Users can’t keep up a façade for long and you’ll notice differences between participants. Developing a rapport with the user can lessen this effect.

Logistics can be more challenging

Field studies can be very simple when you are conducting pure observation. All you need is a pen and paper. Depending on the location, you may not need anyone’s permission so you are free to come and go as you please.

However, most field studies done for product development are more complex because you are interacting with more people (e.g., recruiter, sales person, site contact, other observers, participants, legal departments, etc.) and because more things can potentially go wrong on-site (e.g., broken equipment, missing forms, late arrival, dead batteries). So, field studies are much more challenging to conduct than most other techniques described in this book. Even though your equipment may fail in the lab, you are in a better position to replace/repair it than when you are traveling to an unfamiliar location. You cannot possibly take duplicates of every piece of equipment. In addition, directions to your site may be poor and driving in unfamiliar areas can be stressful. Being detail-oriented, creating a well thought out plan in advance, and piloting everything can help you avoid many problems but there will always be some surprises along the way.

Field Study Methods to Choose From

Field studies come to us from anthropology. Field studies can last from a few hours to days, weeks, or even months depending on the scope of your study and your resources. Before you can begin preparing, you need to understand the techniques available to you. Methods range from pure observation to becoming a user yourself. Table 13.1 is a chart that provides comparisons between the techniques.

Since there is no standard method, we will consider a range of techniques. The goal of each method is the same: to observe users and collect information about their tasks and the context in which they are done. The cost for each method is also very similar (e.g., your time to collect and analyze the data, recording equipment, potential recruitment fees, and incentives). The differences arise in the way you collect data and some of the information you are able to collect.

The techniques described here are divided into three categories: observation only, interacting with the user, and method supplements. The most important thing to remember when designing a field study is to be flexible. Select the method(s) that will best address the goals of your study, as well as the time and resources available to conduct it. Collect several types of data (e.g., notes, audio, video, still pictures, artifacts, sketches, diaries) to obtain a richer data set. Finally, and regardless of the type of study you conduct, do not focus on solutions before or during data collection. Doing that may bias your observations and needlessly limit the information you collect. You can conduct follow-up visits to investigate hypotheses, but – at least in the initial visit – focus on the data collection and keep an open mind.

Observation Only

Techniques that do not involve interacting with users are ideal when you cannot get permission to interview them or when you do not want the users to know you are observing them. There are also cases when you cannot interact with participants (e.g., a doctor in surgery, a trader on the stock exchange floor). Observation-only techniques have their limits in terms of the information that can be collected but they are typically less resource-intensive. There is no set number of users or sites to observe. You simply continue to observe until you feel you understand the users/tasks/environment and you are no longer gaining new insights with each new user or site.

Pure Observation

Ideally, you would like to begin your field study by simply observing. Classic ethnographic methods require one to enter a situation with an open mind (i.e., no preconceived notions or biases). You must spend significant time building sufficient understanding to know what questions to ask and what issues to research. You begin by observing the user, the tasks, and the environment before you ever formulate your first question or study goal. As we mentioned earlier, do not focus on solutions before or during data collection.

In pure observation studies, users may or may not know they are being studied. If you wanted to observe people’s initial reaction to a self-serve kiosk at an airport, you might sit quietly at a well-positioned table and simply record the number of people who saw the kiosk, looked at it, and then used it. You might also capture information such as facial expressions and overheard comments. If you didn’t need photographs or interviews from the participants, you would not need to inform them of your presence. In other situations, however, you will likely need to inform individuals that you are observing them (e.g., in office settings). Refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, page 94, for information about informed consent and appropriate behavior with participants.

Obviously, with this technique you do not interact with the participant. You do not distribute surveys, interview the user, or ask for artifacts from the user. This is simply about immersing yourself in the environment and developing questions along the way. From here, you may go back to your product team and management to recommend additional areas of focus.

The pure observation technique is valuable in situations where you cannot interact with the end users. Perhaps you cannot speak with the end user for privacy or legal reasons (e.g., hospital patients), or it is an environment where you cannot distract the user with questions (e.g., emergency room doctors). The information that you can obtain is obviously limited. You cannot find out why the user did a particular action or how the user completed the task. This is particularly challenging in situations where you are new to the domain and you may not understand much of what you are seeing. In addition, you cannot influence events; you get only what is presented and may miss important events as a result. Consequently, it is essential to have a good sampling plan. The sampling plan should include days/times you anticipate key events (e.g., the day before Thanksgiving, or bad weather at an airport), as well as “normal” days. However, regardless of how good your sampling plan is, you may still miss out on infrequent but important events (e.g., a bad weather closure at the airport, or multiple traumas in the ER). Nevertheless, the information that you can obtain is worthwhile and will bring you closer to understanding the user, tasks, and environment than you were when you began. As Yogi Berra said, “You can see a lot just by watching.”

Deep Hanging-Out

A more structured form of pure observation is referred to as “Deep Hanging-Out.” It involves significant amounts of observation along with involving yourself in the process. In addition, some structure is wrapped around the observation process.

Researchers from Intel developed this method by applying anthropological techniques to field research (Teague & Bell 2001). Their method of Deep Hanging-Out includes structured observation, collection of artifacts, and becoming a user yourself. However, you do not interview participants, distribute surveys, or present design ideas for feedback.

To make this data collection manageable, the system/environment is divided up into ten focus areas, as shown in Table 13.2. The foci are intended to help you think about different aspects of the environment. Because these foci are standardized, you can compare data across multiple sites in a structured manner (to be described in detail later).

Table 13.2

Focal points for Deep Hanging-Out (Teague & Bell 2001)

| Focal point | Some questions to ask |

| Family and kids | Do you see families? How many children are there? What are the age ranges? What is the interaction between the kids? Between the parents and the kids? How are they dressed? Is the environment designed to support families/kids (e.g., special activities, special locations, etc.)? |

| Food and drinks | Are food and drinks available? What is being served/consumed? Where is it served/consumed? When is it served? Are there special locations for it? Are people doing other things while eating? What is the service like? Are only certain people consuming food and drinks? |

| Built environment | How is the space laid out? What does it look like? What is the size, shape, decoration, furnishings? Is there a theme? Are there any time or space cues (e.g., clocks on the walls, windows to show time of day or orientation to the rest of the outside)? |

| Possessions | What are people carrying with them? How often do people access them? How do people carry them? What do they do with them? What are people acquiring? |

| Media consumption | What are people reading, watching, and listening to? Did they bring it with them or buy it there? Where do they consume the media and when? What do they do with it when they are done? |

| Tools and technology | What technology is built in? How does it work? Is it for the customers or the company? Is it visible? |

| Demographics | What are the demographics of the people in the environment? Are they in groups (e.g., families, tours)? How are they dressed? How do they interact with each other? How do they behave? |

| Traffic | What is the flow of traffic through the space? Was it designed that way? What is traveling through the space (e.g., people, cars, golf carts)? Where are the high/low traffic areas? Why are they high/low traffic areas? Where do people linger? |

| Information and communication access | What are the information and communication access points (e.g., pay phones, ATMs, computer terminals, kiosks, maps, signs, guides, directories, information desks)? Do people use them, and how often? How do people use them? Where are they located (e.g., immediately visible, difficult to access)? What do they look like? |

| Overall experience | Don’t forget the forest for the trees. What is the overall environment like? What is the first and last thing you noticed? What is it like to be there? How is it similar or different from similar environments? Are there any standard behaviors, rules, or rituals? [Think high level and obtain a holistic view, rather than concentrating on details.] |

Breadth can be important, even at the expense of depth, when first learning about an area. One use of the list in Table 13.2 is to remind you to focus on a large number of areas and not focus on just one small (easy to collect) area. This list is particularly useful for a novice – to appreciate all the areas to look at and to understand that depth in every area isn’t that important.

Another key use of the list is to help teams who are doing research together to come away with better findings. Many times a group of four to five people go out and conduct observations independently but they all come back with pretty much the same findings. This can be frustrating for everyone involved and may cause stakeholders to question the value of having so many people involved in the study or the value of the study period. Using the list of foci and giving each person a specific focus area helps to ensure that the team examines multiple areas. In addition, it gives individuals some direction and ownership and makes their insight a unique contribution to the team.

Numerous studies at Intel demonstrated that, regardless of the system, users, or environment they studied, these ten foci represented the domain and supported valuable data collection. The technique is intended to be flexible. There is no minimum number of foci to collect data about or recommended amount of time to spend observing each focus area. However, even if a particular focal point does not seem appropriate to your study, you should still try to collect information about it. The lack of information about that particular focal point can be just as enlightening! For example, you may think that the “Family and kids” focal point is not appropriate when you are studying users in their office environment. Who brings their family to work with them? But, you may observe that a user is constantly getting calls from a spouse and pages from the kids. Perhaps they are complaining because your user is never home or is late for the daughter’s recital. Maybe this means that the user is so overwhelmed with work that problems with the family life are spilling over into work, and vice versa. Even if you do not think a particular focal point is applicable to your study, you should remember to go in with an open mind!

Just as with observation only when creating your sampling plan, we recommend collecting data at different times during the day and on different days of the week. For example, you would likely observe different things if you went to the airport at 8 am on Monday, 8 am on Saturday, and 6 pm on Wednesday.

Deep Hanging-Out stresses that you are “on” at all times. Using our earlier travel example, you would begin your observations from the time you travel to the airport. Observe the experience from the very beginning of the process, not just once you are inside the airport. Pay attention to the signs directing you to parking and passenger pick-up. The intention is to obtain a holistic view of the system/environment that goes beyond Contextual Inquiry (discussed on page 580).

While you are observing the users and environment, create maps (see Figure 13.1). Identify where actions occur. If your focus is “Family and kids,” identify locations designed for families or kids (e.g., jungle gym, family bathroom). Where do families tend to linger? In addition to creating maps, collect maps that the establishment provides. Collect every artifact you can get your hands on (e.g., objects or items that users use to complete their tasks or that result from their tasks). If allowed, take photos or videos of the environment. You may need to obtain permission first, so keep this in mind.

Finally, involve yourself in the process by becoming a user. If you are interested in designing a kiosk at an airport, use each kiosk currently at the airport but never mistake yourself for the actual end user. Involving yourself in the process helps you understand what the users are experiencing, but it does not mean that you are the end user.

Interacting with the User

For actual product development (not just learning about a domain or preparing for another usability activity), it is almost always better to interact with users rather than just observe them. You will not get enough information to design from observation alone. You frequently need to follow-up an observational study with an interaction study. Several techniques are available to you to accomplish this, including:

Contextual Inquiry

Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998) wrote the book on Contextual Inquiry (CI) and Contextual Design. This is a very detailed method and we are unable to cover all of the fine points in this chapter. However, because this is a very popular and useful method, we would like to introduce you to the basics. For more details, please refer to the Suggested Resources box.

There are four main parts to Contextual Inquiry:

![]() Context. You must go to the user’s environment in order to understand the context of his/her actions. Contextual Inquiry assumes that observation alone or out-of-context interviews are insufficient.

Context. You must go to the user’s environment in order to understand the context of his/her actions. Contextual Inquiry assumes that observation alone or out-of-context interviews are insufficient.

![]() Partnership. To better understand the user, tasks, and environment, you should develop a master-apprentice relationship with the participant. Immerse yourself in the participant’s work and do as he/she does. Obviously, this is not possible with many jobs (e.g., surgeon, fighter pilot).

Partnership. To better understand the user, tasks, and environment, you should develop a master-apprentice relationship with the participant. Immerse yourself in the participant’s work and do as he/she does. Obviously, this is not possible with many jobs (e.g., surgeon, fighter pilot).

![]() Interpretation. Observations must be interpreted with the participant in order to be used later. Verify that your assumptions and conclusions are correct.

Interpretation. Observations must be interpreted with the participant in order to be used later. Verify that your assumptions and conclusions are correct.

![]() Focus. Develop an observation guide to keep you focused on the subject of interest/inquiry.

Focus. Develop an observation guide to keep you focused on the subject of interest/inquiry.

Unlike the methods described earlier, the user is very aware of your presence and becomes a partner in the research. Contextual Inquiry is more focused and context dependent than the previous methods. It can also be faster, taking only a few hours or a day. At the end, you walk away with actionable items to begin designing a product, your next usability activity (e.g., tasks for a usability test, questions for a survey), or areas for innovation and future research.

The process begins by developing an observation guide (see Figure 13.2). This is a list of general concerns or issues to guide your observations – but it is not a list of specific questions to ask. You may want to refer to the foci listed in Table 13.2 to build your observation guide. Using a travel agent observation example, some issues to look out for might be sources for travel research, interactions with co-workers, and length of time spent doing research for an individual client. This observation guide would obviously be influenced by the goals of your study and what you want to learn.

Next, you carefully select a few representative users to observe and apprentice with. Beyer and Holtzblatt recommend 15–20 users, but four to six is more common in industry practice. The number of participants used should be based on the question you are trying to answer. The more focused (or narrow) the question and the more consistency across users, tasks, and environments, the fewer participants are necessary. For example, if you are interested in studying only one particular task that a travel agent does rather than his/her job in general, you could observe fewer participants and feel more confident in the reliability of the results.

Context

Work with participants individually. Begin by observing the participant in action. The goal is to collect ongoing and individual data points rather than a summary or abstract description of the way the participant works. It is best to have one note-taker and one interviewer present. You can ask the participant to think-aloud as he/she works (refer to Chapter 6, During Your User Requirements Activity, “Introducing Your Think-aloud Protocol” section, page 218), or you may choose to ask the participant clarifying questions along the way. You may even decide not to interrupt the participant at all but wait until he or she has completed a task and then ask your questions. Your choice should depend on the environment, task, and user.

For example, travel agents would not be able to think-aloud as they book travel plans for clients over the phone. It would also cause confusion and annoy participants if you interrupted them with questions during the call. It is best in that case to wait until the travel agent has concluded the call and then ask your questions. Task clarification questions in the case of a hotel booking might include: “How did you determine the rate?”, “Why did you ask the customer if she had AAA membership?”, and “How were you able to pull up the customer’s personal profile?”

Partnership

Once the participant is comfortable with your presence and you have developed a rapport, you can introduce the master-apprentice relationship. (Refer to Chapter 7, Interviews, “Monitoring the Relationship with the Interviewee” section, page 290 to learn about developing a rapport with participants.) As long as the company approves it and you are not breaking any laws, the participant becomes the master and instructs you (the apprentice) on how to complete a given task. You could not apprentice next to an emergency room physician unless each patient gave you permission; but considering the nature of emergencies, it is not likely that your presence could be easily accommodated. Despite limitations in some environments, the participant can always instruct you on some aspect of his/her activities.

It is easy for certain types of relationships to develop during this time. You should avoid the three relationships listed below because they are not conducive to unbiased data collection.

![]() Expert-novice. Because you are entering the environment as a “specialist,” the user may see you as the expert. It is important for you to remind the participant that he or she is the expert and you are the novice.

Expert-novice. Because you are entering the environment as a “specialist,” the user may see you as the expert. It is important for you to remind the participant that he or she is the expert and you are the novice.

![]() Interviewer–interviewee. Participants may assume that this is an interview and, if you are not asking questions, you already understand everything. Stress to the participant that you are new to the domain and need to be instructed as if you were a new employee starting the job. The user should not wait for questions from you before offering information or instruction.

Interviewer–interviewee. Participants may assume that this is an interview and, if you are not asking questions, you already understand everything. Stress to the participant that you are new to the domain and need to be instructed as if you were a new employee starting the job. The user should not wait for questions from you before offering information or instruction.

![]() Guest–host. You are a partner with the user and should be involved with the user’s work. The user should not be getting you coffee, and you should not be concerned about invading the user’s personal space. Get in there and learn what the user knows.

Guest–host. You are a partner with the user and should be involved with the user’s work. The user should not be getting you coffee, and you should not be concerned about invading the user’s personal space. Get in there and learn what the user knows.

Interpretation

Interpretations of the data you collect will drive future decisions, so it is critical that those interpretations are correct. As you work with participants, share your interpretations with them and verify that you are correct. You do not have to worry that users will agree with an incorrect interpretation just to please you. When you create a solid master-apprentice relationship, the user will be keen for you to understand the process and will correct any misconceptions you have. He or she will often add to your interpretations as well, extending your knowledge and understanding of what you have observed.

Remember what your teacher told you: “The only dumb questions are the ones you don’t ask.” Do not be afraid to ask even simple questions. In addition to increasing your own knowledge, you can make the participants think more about what they would consider “standard practices” or the “that’s just the way we have always done it” mentality. (Refer to Chapter 7, Interviews, “Your Role as the Interviewer” section, page 277, for tips about communicating with users and helping them provide the information you are seeking.)

Focus

During the entire process, you want to keep the inquiry focused on the areas of concern. You began by developing an observation guide for the inquiry (see above). Refer to this guide throughout the process. Since the participant is the master, he or she will guide the conversation to points he/she finds of interest. It is essential for you to learn what the participant finds important, but it is also critical that you get the data necessary to guide your design/next usability activity/innovation. The user may find it more interesting to cover all topics at a high level, but your focus should uncover details in the areas that you believe are most important. “The devil is in the details” – if you do not uncover the details, your interpretation of the data will be inadequate to inform design/the next usability activity/innovation. (Refer to Chapter 7, Interviews, “Your Role as the Interviewer” section, page 277, to learn more about guiding the participant’s conversation.)

Process Analysis

A process analysis is similar to Contextual Inquiry. Unlike Contextual Inquiry, however, you enter with a series of questions (see below) and you do not necessarily apprentice with the user. It is a focused type of field study targeted at understanding the task sequence for a process that may span several days. At the end, you can develop a process map that visually demonstrates the steps in a process. (Figure 13.3 illustrates a very simple process map for a travel agent.) Because process analysis is more focused than Contextual Inquiry, it is also much faster to conduct.

![]() When does the first task in the process happen?

When does the first task in the process happen?

![]() What information does the person have when the task begins?

What information does the person have when the task begins?

![]() What are the major steps in the task?

What are the major steps in the task?

![]() What information comes out of it?

What information comes out of it?

![]() Who is the next person in the chain of the process?

Who is the next person in the chain of the process?

![]() When does the next task happen? [repeat for each task in the process]

When does the next task happen? [repeat for each task in the process]

![]() How do you know when the process is complete?

How do you know when the process is complete?

![]() Does this process connect to other processes?

Does this process connect to other processes?

![]() Is this process ever reopened and, if so, under what circumstances?

Is this process ever reopened and, if so, under what circumstances?

![]() What errors can be made? How serious are they? How often do they occur?

What errors can be made? How serious are they? How often do they occur?

Condensed Ethnographic Interview

Based on the cognitive science model of expert knowledge, the condensed ethnographic interview employs the standardization and focus of a semi-structured interview (refer to Chapter 7, Interviews, page 246) along with the context of observations and artifacts. Users are first interviewed to ask them how they accomplish a task, as well as other information surrounding their work. Users are then observed doing the task(s) in question, focusing on processes and tools. Artifacts are collected and discussed. Rather than a general observation guide, investigators use a standard set of questions to guide the visits but remain flexible throughout. One researcher developed a model of the users’ work and then asked experts for validation/correction (Wood 1996).

This approach is characterized as “top-down” – in contrast to Contextual Inquiry’s “bottom-up” approach – because the interviews form a general framework from which to interpret specific observations. This technique is considerably shorter than some of the other techniques described above but it also limits the data you are able to collect.

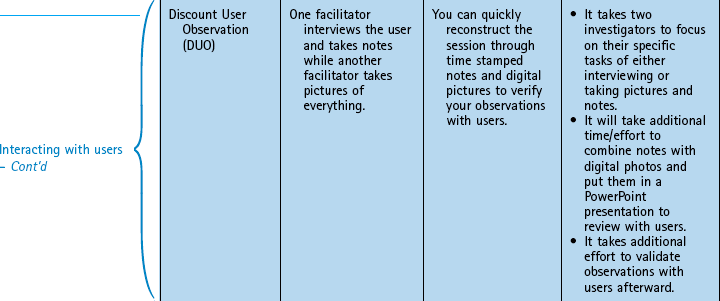

Discount User Observation (DUO)

Three usability professionals created a method of collecting, analyzing, and presenting observational data in a shorter time frame than other methods they were familiar with – such as Contextual Inquiry (Laakso, Laakso, & Page 2001).

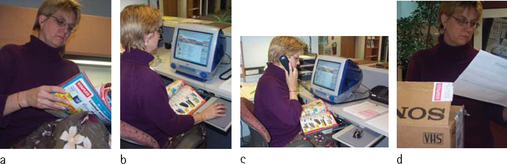

“Discount User Observation” (DUO) requires two data collectors. The first is a note-taker and is responsible for taking detailed notes during the visit, as well as asking clarifying questions. The questions should not disrupt the user’s activities and should not turn into an interview. It is best to save questions until the end. Also, it is important that all notes be time-stamped. Notes can be taken either by hand or on a laptop. Using Microsoft Excel, you can write a program that automatically time-stamps each data entry. This would be less resource-intensive and error prone. See Figure 13.4 for a sample of time-stamped notes.

The second data collector is a photographer. The key difference between DUO and other methods is the critical aspect of collecting digital photographs of artifacts (e.g., printouts, business cards, notes, day planners) and the environment. Digital cameras typically include automatic time-stamps. Combining the time-stamped notes with the time-stamped photos provides a timeline of the user’s work. Following data analysis, a summary of the results is presented to users for verification and correction (see “Data Analysis and Interpretation,” page 615).

The goal of this discount method is not to save time by focusing in on any specific area of the user’s work or environment, but rather to capture a holistic picture of the user’s work, environment, and tasks. The goal is to understand the complex interdependencies of tasks, interruptions, and temporal overlaps (i.e., two actions occurring at the same time) without having to spend significant amounts of time transcribing, watching videos, or confusing raw data with inferences and interpretations.

Method Supplements

There are three activities that you can conduct in addition to the above methods, or use as standalone techniques: artifact walkthroughs, incident diaries, and observing while absent. They all require participation from the user, so they are not useful when conducting observation-only studies.

Artifact walkthroughs

Artifact walkthroughs are quick and easy but provide indispensable data. Begin by identifying each artifact a user leverages to do a particular task. Artifacts are objects or items that users use to complete their tasks or that result from their tasks. These can include the following:

![]() “Official” documents (e.g., manuals, forms, checklists, standard operating procedures)

“Official” documents (e.g., manuals, forms, checklists, standard operating procedures)

![]() Documents that get printed out as needed and then discarded

Documents that get printed out as needed and then discarded

![]() Communications (e.g., inter-office memos, e-mails, letters)

Communications (e.g., inter-office memos, e-mails, letters)

![]() Outputs of tasks (e.g., confirmation number from travel booking).

Outputs of tasks (e.g., confirmation number from travel booking).

You want to understand what triggers the use of each artifact: when is it used, and for what. Whenever possible, get copies of each artifact. If there are concerns about sensitive or private information (e.g., patient information, credit card numbers), ask for a copy of the original, black out the sensitive data, and then make a second copy. This takes a little extra time but most participants are willing to help wherever possible. You can also sign the company’s confidential disclosure agreement promising that you will keep all data collected confidential (refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, “Legal Considerations” section, page 103). The information obtained during an artifact walkthrough will be essential if you want to conduct an artifact analysis (see “Data Analysis and Interpretation,” page 615).

Incident diaries

Another technique that works well in field studies is the incident diary. Incident diaries allow you to collect ongoing data from users rather than one-time performance or opinions. They are given to users to keep track of issues they encounter while using a product.

Participants are provided with a notebook containing worksheets to be completed at home or work on their own (i.e., when you are not around to observe). The worksheets may ask users to describe a problem or issue they encountered, how they solved it (if they did), and how troublesome it was (e.g., Likert scale). The exact content of the worksheet will depend on the goals of the study. The purpose of incident diaries is to understand infrequent tasks that you might not be able to see even if you observed the user all day. In the example shown (see Figure 13.5), planning a vacation often happens over an extended period and during unplanned times. You cannot possibly be there to observe on all of those occasions and you do not want to interrupt their natural behavior. Finally, incident diaries can also be used while you are present to get two different perspectives on the same issue (e.g., during a usability evaluation).

The appeal of incident diaries is that they require little time or resources on your part. However, there are several issues with using incident diaries which call into question their validity and reliability:

![]() They are best used when problems or tasks are relatively infrequent. It is important to remember that frequency does not equate with importance. Some very important tasks happen very rarely but you need to capture and understand them. Frequent tasks can and should be observed directly, especially since users are usually unwilling to complete worksheets every few minutes for frequent tasks.

They are best used when problems or tasks are relatively infrequent. It is important to remember that frequency does not equate with importance. Some very important tasks happen very rarely but you need to capture and understand them. Frequent tasks can and should be observed directly, especially since users are usually unwilling to complete worksheets every few minutes for frequent tasks.

![]() When you are not present, there is a chance that users will not remember (or want) to fill out the diary while they are in the middle of a problem. There is no way of knowing whether the number of entries matches the number of problems actually encountered.

When you are not present, there is a chance that users will not remember (or want) to fill out the diary while they are in the middle of a problem. There is no way of knowing whether the number of entries matches the number of problems actually encountered.

![]() The user may not provide enough detail or context for the entry to be meaningful.

The user may not provide enough detail or context for the entry to be meaningful.

![]() The user may lack the technical knowledge to accurately describe the problem.

The user may lack the technical knowledge to accurately describe the problem.

![]() User perception of the actual cause or root of the problem may not be correct.

User perception of the actual cause or root of the problem may not be correct.

Despite these issues, incident diaries can give you additional insight into the user experience over time that you would not otherwise have. The caution here is not to use incident diaries in isolation. Follow-up with interviews or other usability activities.

Observing while you are not present

You can observe users even when you are not present by setting up a video camera and then leaving. This is an excellent way to understand detailed steps a user takes, especially in small environments where observers cannot fit or critical jobs where you do not want to interrupt/distract the user. In one study, researchers videotaped radiologists at work, viewed the tapes later, and formulated questions (Ramey, Rowberg, & Robinson 1996). They then set up another appointment with the radiologists about three days later to view the tapes together while the radiologists provided a running commentary (called “retrospective think-aloud” or “stimulated recall”). The interviewers inserted questions along the way. They refer to this technique as “stream-of-behavior chronicles.” To analyze the data, they categorized and indexed specific behaviors.

In another example of recording user behavior, investigators videotaped the participant’s setting and captured the participant’s computer screen (Bauersfeld & Halgren 1996). This was recorded as a picture-in-picture image with a video mixer. The user could turn the recording on and off as needed (e.g., turn off the recording to read personal e-mail). The investigators then came back two to three hours later to collect the equipment and analyze the tapes. If you have several cameras, you can record the behavior of several participants simultaneously.

Preparing for a Field Study

Now that you are familiar with some of the techniques available to you, it is time to plan and prepare for your field study. Although some of the details may vary slightly depending on the data collecting technique selected, the preparation, participants, and materials remain constant.

Identify the Type of Study to Conduct

To identify the type of study you would like to conduct, use the decision diagram in Figure 13.6.

Scope your study appropriately. You may not have time to learn everything you would like to, or be able to visit all the sites you are interested in. It is critical to the success of your study to plan carefully. Create a realistic timetable for identifying the sites, recruiting the users, collecting the data, and then analyzing the data. You will have questions later on (usually during the analysis stage). If possible, leave enough time to conduct follow-up interviews. There is nothing more frustrating than running out of time and not being able to analyze all the data you have! And remember, it always takes longer than you think – so include enough extra time in case you run into snags along the way.

Write a proposal (refer to Chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Creating a Proposal” section, page 146) that establishes the objectives of the study, identifies the user and site profile, the timeline, the resources needed (e.g., budget, materials, contacts, customers) and from whom, as well as how the information you collect will benefit the company/product/design. If you cannot provide this information, you have more research to do. It is essential that you get buy-in from all stakeholders on this proposal. You do not want stakeholders changing their focus or disagreeing about the direction of your study halfway through. The proposal will be your stake in the ground.

Players in Your Activity

In addition to participants to observe, there are a few other roles you may need to fill for your study. Each one is described below.

The participants

Once you know the type of study you would like to conduct, you need to identify the user type to investigate (refer to Chapter 2, Before You Choose an Activity, “Learn About Your Users” section, page 41). As with any of the techniques described in this book, the data you collect are only as good as the participants you recruit.

Create a screener to guide your recruitment and make sure everyone is in agreement (refer to Chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Recruitment Methods” section, page 173).

There is no set number of users to recruit. As mentioned earlier, some people recommend 15–20 users, but time and cost restraints mean that four to six (per user type) is more common in industry practice. There are other factors to keep in mind when identifying users and sites for field studies. These include:

Diverse range of users and sites

Get a broad representation of users and sites. This includes industry, company size, new adopters and long-time customers, as well as geographical diversity. Try to get access to multiple users at each site. They may be doing the same task, but each person may do it differently, have different ideas, challenges, workarounds, etc. You also want a mix of experts and novices. Contacts at a given company will likely introduce you to their “best” employees. Explain to the contacts the value in observing both expert and novice users. In the end, though, politics and people’s availability may determine your choice of sites and users to observe. Just make sure the participants and sites meet your profile, otherwise there is no point in collecting the data. Also, try to get stakeholders involved in identifying sites, users, and contacts at those sites. They often have the contacts to help you do this.

When you begin recruiting, start small; do not recruit more users or sites than your schedule will permit. If your first set of visits is successful, you can leverage that success to increase the scope of your study. In addition, you may need to start with local sites for budgeting reasons; but if your study is successful, you could be given the opportunity to expand later.

Setting company expectations up-front

Some companies may insist, as a condition of participating, on seeing the results of your study or receiving a report on their employees. Be clear and set their expectations at the beginning; you are not there to report on the employees – it is unethical and may be a violation of labor laws. In addition, you cannot provide information gained from another company. Most often, companies will ask you to sign a confidential disclosure agreement to ensure that you will keep their data confidential (refer to Chapter 3, Ethical and Legal Considerations, page 94). You may offer to provide a copy of the notes from the sessions conducted at their site, or a very general summary, but first speak with your legal department to get permission.

Do not reveal the names of the people who participated in your study. The actions and comments you observed should not be associated with specific participants.

Some conclusions and design recommendations that you develop as a result of the site visits could be deemed confidential by your company, so you may not be able to share this information with the companies that participated.

Once you explain all this, most site contacts will understand your position. Some may still feel that you are not providing them with enough information to make participation worthwhile. Explain the benefit they will see in a new or improved product. However, if that is not incentive enough, you must move on to another site.

The investigators

Begin by identifying who wants to take part as genuine data collectors, not just as curious onlookers. You may be surprised to discover how many people want to be present during your field visits, particularly those visits in which you intend to interact with customers. In purely observational or Deep Hanging-Out studies (as described above), this is not a big issue. You should welcome some additional help in collecting data. It will speed the process, and an additional set of eyes can bring a fresh perspective to the data analysis. Expect and encourage people to get involved, but be aware of some of the issues surrounding inexperienced investigators.

You may want to establish a rule that anyone present at the site must participate in the data collection and follow a set of ground rules (see “Train the Players,” page 598). This is where you must establish yourself as the expert and insist that everyone respect your expertise. Sometimes you need to be diplomatic and tell a stakeholder that he/she cannot attend a particular visit, without ruining your relationship with that stakeholder.

Once you have a list of people who want to take part in the study, look for those who are detail-oriented, and good listeners. We recommend working in teams of just two, because that is less overwhelming for the participant being observed. Each team should consist of an investigator and a note-taker, and a videographer/ photographer (see below). Since the video camera can usually be set up in the beginning and left alone, either the investigator or note-taker can do this. And because three people can be overwhelming for a user, we recommend that either the note-taker or investigator double-up as photographer. Mixed-gender teams can help in cases where a participant feels more comfortable relating to one gender or another.

The job of the investigator is to develop rapport with the participant, and if applicable, conduct the interview and apprentice with him/her. The investigator is the “leader” in the two-person team. In cases where you lack a great deal of domain knowledge, you may not know enough about what you are observing to ask the user follow-up questions later on. You may wish to create more of a partnership with a developer or product manager. You can begin by asking participants each question, but the domain expert would then follow up with more detailed questions. Just be sure that one of you is capturing the data! Alternatively, you can bring a “translator” along with you. This may be a user from the site or an expert from your company who will provide a running commentary while the participant is working. This is ideal in situations where the participant cannot provide think-aloud data and cannot be interrupted with your questions. In a healthcare field study we conducted, we asked a member of the product team who was a former Registered Nurse to act as a translator for us. She pointed out observations that were interesting to her and which we would not have noticed. She also explained the purpose of different artifacts when users were not available to discuss them. Her help was priceless on-site!

If you have more potential investigators than you have roles, you may choose different investigators for each site. This can lower inter-rater reliability (i.e., the degree to which two or more observers assign the same rating or label to a behavior), but it may also be necessary if individual investigators do not have the time to commit to a series of visits. Having a single person who attends all visits (i.e., yourself) can ensure continuity and an ability to see patterns/trends. Having a new investigator every few visits provides a fresh set of eyes and a different perspective. It also breaks up the workload and allows more people to take part in the study. You are sharing the knowledge, and important stakeholders do not feel excluded.

If time is a serious issue for you, it may be wise to have more than one collection team. This will allow you to collect data from multiple sites at once, but you will need to train several people and develop an explicit protocol for investigators to follow (see “Develop Your Protocol,” page 599). If there is more than one experienced usability professional available, pair each one up with a novice investigator. Having more than one collection team will mean that you will lose that consistent pair of eyes, but it may be worthwhile if you are pressed on time but have several sites available to you.

The note-taker

In addition to an investigator, a note-taker is required. The investigator should be focused on asking questions and apprenticing with the user (if applicable), not taking detailed notes. You will find a detailed discussion of note-taking tips and strategies in Chapter 6 (refer to Chapter 6, During Your User Requirements Activity, “Recording and Note-taking” section, page 226). The note-taker can also serve as a timekeeper if that is information you wish to collect. You may also wish to have the note-taker serve as the videographer/photographer (see below). Lastly, it is also important to have an additional pair of hands on-site to set up equipment, and the note-taker can serve this purpose.

The videographer/photographer

Whenever possible you will want to video record your field study. You will find a detailed discussion of videotaping tips and the benefits of videotape in Chapter 6 (refer to Chapter 6, During Your User Requirements Activity, “Recording and Notetaking” section, page 226). In most cases, this person simply needs to start and stop the tape, insert new tapes as needed, and keep an eye out for any technical issues that arise.

You may also want someone to take photographs. (Again, the note-taker can often take on the roles of videographer and photographer.) Capturing visual images of the user’s environment, artifacts, and tasks is extremely valuable. It helps you remember what you observed, and it helps stakeholders who were not present to internalize the data. Even if you do not plan to include pictures of participants in your reports or presentations, they can help you remember one participant from another. A digital camera is advantageous, because if the user is nervous about what you are capturing, you can show him/her every image and get permission to keep it. If the user is not happy with the image, you can demonstrate that you deleted it.

Account managers

The account manager or sales representative is one person who may insist on following you around until he or she feels secure in what you are doing. Since this is the person who often owns the sales relationship with the customer and must continue to support the customer after you are long gone, you need to respect his/her need for control. Just make sure the account manager understands that this is not a sales demo and that you will be collecting the data. We have experienced this ourselves in more than one study. We have found that account managers are so busy that they will often leave you after an hour or less.

Train the Players

You are entering someone’s personal space; for some users, this is often more stressful for the user than going to a lab. You will also likely need to leverage multiple skill sets such as interviewing, conducting surveys, observing, and managing groups of people. If you or a co-worker has not conducted a field study before, we recommend reviewing Chapter 6, During Your User Requirements Activity, “Moderating Your Activity” section, page 220, for a foundation in moderating. You may also want to sign up for a tutorial at a conference hosted by a relevant professional organization to get hands-on training for one of the particular techniques. Shadowing an experienced usability professional is another option, but it is more difficult to do since the primary investigator will want to reduce the number of observers to an absolute minimum.

Even if the people available to collect data are all trained usability professionals, you want to ensure that everyone is on the same page – so a planning and/or training session is essential. Begin by identifying roles and setting expectations. If you need the other investigator to help you prep (e.g., copy consent forms, QA equipment), make sure he or she understands the importance of that task. You do not want to get on-site only to find that you don’t have the consent forms because of miscommunication or because the other investigator was annoyed at being your “assistant.” Also make sure that everyone is familiar with the protocol that you will be using (refer to Chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Creating a Protocol” section, page 190).

If you will be conducting usability evaluations on-site, make it clear to all investigators that they are not there to “help” the participant. It is human nature to want to help someone who is having difficulty, but all the investigators need to remember that they will not be there to help the user later on. One usability professional keeps a roll of duct tape with him and shows it to his co-investigators prior to the visit. He informs them that he will not hesitate to use it should they offer inappropriate help or comments during the visit. It gets a laugh and helps them to remember the point.

If this will be a large field study (rather than a one-time visit), you may want inexperienced investigators to read this chapter, attend workshops, practice during mock sessions, or watch videos of previously conducted field studies. Develop standardized materials (see “Activity Materials,” page 603) and review them with all investigators. Additionally, everyone should know how to use each piece of equipment. Practice setting up and packing up equipment quickly. Labeling cords for easy identification will make setting up much faster. Finally, identify a standard notetaking method and shorthand for easy decoding.

Develop your Protocol

By now, you have selected the type of field study you will conduct. Now you need to identify your plan of attack or protocol. This is different from your observation guide (a list of concerns or general areas to observe). A protocol can include how you will interact with users (the observation guide is part of that), how much time you plan to spend observing each user/area, and what instructions you will give users (e.g., think-aloud protocol). You should also identify any activities that you want other investigators to participate in. The answers to these and many other questions need to be spelled out in a protocol (refer to Chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Creating a Protocol” section, page 190). Without a protocol, you do not have a script for everyone to follow and each investigator will do his/her own thing. Even if you are doing the study alone, you may end up conducting each visit differently, forgetting some questions, haphazardly adding in others. A protocol allows you to collect the data in the most efficient and reliable manner possible. It also allows you to concentrate on the data collection, not trying to remember what you forgot this time.

Schedule the Visits

After you have selected your investigators, get commitment from each one and include them in scheduling discussions. They must agree to be present at the visits they are scheduled for, and they must be willing to receive training. If they do not have time for either of these, it is best to find someone else.

Below are some things to consider when scheduling your visits. The questions below may seem obvious, but when you are in the middle of creating the schedule, many “obvious” details are forgotten.

![]() Where is the site? How long it will take to get there? If there will be a significant drive and traffic will likely be a problem, obviously you do not want to schedule early morning appointments.

Where is the site? How long it will take to get there? If there will be a significant drive and traffic will likely be a problem, obviously you do not want to schedule early morning appointments.

![]() Have you checked to see if your contact or the user’s manager should be called or scheduled as part of the visit?

Have you checked to see if your contact or the user’s manager should be called or scheduled as part of the visit?

![]() Do you plan to visit more than one site per day? How far apart are they? Will there be traffic? What if you are running behind schedule at the other site? If you must visit more than one location per day, put in plenty of pad time between sites.

Do you plan to visit more than one site per day? How far apart are they? Will there be traffic? What if you are running behind schedule at the other site? If you must visit more than one location per day, put in plenty of pad time between sites.

![]() Include breaks between users or sites in your schedule. This will allow you to review your notes, rest, eat a snack, check your messages, etc. You do not want a growling stomach to interrupt your quiet observations.

Include breaks between users or sites in your schedule. This will allow you to review your notes, rest, eat a snack, check your messages, etc. You do not want a growling stomach to interrupt your quiet observations.

![]() Make sure you are refreshed for each visit. If you are not a morning person, do not schedule early morning appointments; or if your energy tends to run out at the end of the day, schedule only one visit per day. Clearly, you do not want the user to see you yawning during the interview.

Make sure you are refreshed for each visit. If you are not a morning person, do not schedule early morning appointments; or if your energy tends to run out at the end of the day, schedule only one visit per day. Clearly, you do not want the user to see you yawning during the interview.

– Lunchtime may either be good or bad for users. Find out what they prefer as well as what their workload might be during that time (see next point).

– Some users want you there when work is slow so you won’t disturb them. Obviously, you want to be there when things are busy! Make sure that the time the user suggests for your visit will allow you to observe what you are interested in.

– Consider the cyclical nature of work. Some tasks are done only during certain times of the year. Going back to the vineyard study mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, if you are interested in observing the harvest, there is a limited window in which you can observe.

– Some days of the week are worse than others (e.g., Monday and Friday). As a general rule, avoid Monday mornings and Friday afternoons. Also find out if there are standard “telecommuting” days at your user’s site?

– Be prepared to compromise. Your users have lives to live and your study is likely low on their priority list. You may have to change your original plan or schedule, but keep in mind that some data are better than none.

![]() Do not forget the other investigators. Ask them for their availability. Find out whether they are morning or evening people. It isn’t any less offensive for the note-taker to be yawning during an interview.

Do not forget the other investigators. Ask them for their availability. Find out whether they are morning or evening people. It isn’t any less offensive for the note-taker to be yawning during an interview.

![]() Find out how to make copies or print out files. Can you use the user’s facilities or will you have to find a local copy shop?

Find out how to make copies or print out files. Can you use the user’s facilities or will you have to find a local copy shop?

![]() Finally, consider the haphazard schedule of some occupations (e.g., surgeons, emergency medical technicians). They may agree to participate but be pulled away to activities you cannot observe. Be prepared to wait long periods of time. Bring other work with you to do and/or have a list of things to observe that do not require interacting with participants. Also be prepared to take advantage of sudden opportunities.

Finally, consider the haphazard schedule of some occupations (e.g., surgeons, emergency medical technicians). They may agree to participate but be pulled away to activities you cannot observe. Be prepared to wait long periods of time. Bring other work with you to do and/or have a list of things to observe that do not require interacting with participants. Also be prepared to take advantage of sudden opportunities.

Begin your study on a professional foot. When recruiting individuals over the phone, they may be skeptical. You must demonstrate that you are not trying to sell them a timeshare in Florida and you can be trusted. If your company is not well known, point people to your website for legitimacy. Give them your name and call-back information. Obviously, you should be polite even if the person on the other end is not.

If the potential participant or site contact is interested, provide all logistical details up-front (e.g., dates, times, length of stay, etc.). Get names, e-mail addresses, and phone numbers for each person you plan to speak with (not just their supervisor’s or the account manager’s information). You need this information to follow up, ask questions, and resolve issues that may arise. If the supervisor or account manager is absent, you may be unable to find your next appointment or learn that the person you are supposed to be interviewing went home sick (see “Lessons Learned,” page 623). Finally, call the night before to confirm your appointment and answer any lastminute questions the participant or site contact may have.

The final thing to keep in mind when scheduling is burnout. Burnout is a risk for extended studies. Field studies are intense activities where you must be “on” at all times. It is time-consuming to conduct each visit and analyze the data. You can also suffer from information overload. All of the sites or users tend to blur together after a while. And travel can be stressful. Take the “fatigue factor” into consideration when scheduling the visits and determining the timeline for analyzing data. Unfortunately, you may be placed in the situation where you must visit six sites in three days and there is no way around it. Alternating the roles of note-taker and interviewer between yourself and your co-worker can give you a break. At least you will not have to be “on” for every participant (encouraging participants to think-aloud, following up on questions, apprenticing). You will still be exhausted, but since you get a “break” every other participant, the data collected will hopefully not be degraded.

Activity Materials

You may have many materials to take to each site; it depends on the type of study you are conducting and what is permitted on-site. Below is a list of suggested materials for most types of studies, but you should tailor this for your own study and include more detail in your own checklist. Some of these materials may not be familiar to you, but they are all described later. This is the best way to stay organized and keep your study running smoothly from one site to the next. Without your checklist, you will likely forget at least one thing each time out.

Checklist of all materials and equipment needed

![]() Contact information for each participant

Contact information for each participant

![]() Consent forms and confidentiality agreements

Consent forms and confidentiality agreements

![]() Method of note-taking (audio recorder and/or paper and pencil)

Method of note-taking (audio recorder and/or paper and pencil)

![]() Peripherals (e.g., batteries, tapes, extension cords, power strip)

Peripherals (e.g., batteries, tapes, extension cords, power strip)

![]() Method for collecting artifacts (e.g., accordion folder, notebook, hole puncher)

Method for collecting artifacts (e.g., accordion folder, notebook, hole puncher)

![]() Method for carrying all the equipment (e.g., small suitcase, luggage cart)

Method for carrying all the equipment (e.g., small suitcase, luggage cart)

![]() Thank you gift for participant(s)

Thank you gift for participant(s)

![]() Business cards for participants to contact you later with questions or additional information

Business cards for participants to contact you later with questions or additional information

![]() Video recorder or camera and audio recorder (if permission has been obtained to record).

Video recorder or camera and audio recorder (if permission has been obtained to record).

We recommend providing an incentive for participants (refer to Chapter 5, Preparing for Your User Requirements Activity, “Determining Participant Incentives” section, page 159). We also recommend getting a gift for anyone who helped arrange your access to the site or users (e.g., account/product manager). This individual may have spent significant time finding people in the company to match your user profile, or helping you to arrange your visit. It never hurts to show your appreciation and it can also help if you ever need to access that site again. When selecting the gift, keep in mind that you must carry it along with the rest of your equipment. You don’t want to carry around several shirts in each size or heavy, breakable coffee mugs.

As we mentioned earlier, it is important to develop an observation guide. This is a list of general concerns or issues to guide your observations but it is not a list of specific questions to ask. This will help ensure you address each of the goals of your study. Next, use your observation guide to develop a visit summary template (see Figure 13.7). This is a standardized survey or worksheet given to each investigator to complete at the end of each visit. This helps everyone get their thoughts on paper while they are fresh. It also speeds data analysis and avoids reporting only odd or funny anecdotal data. Although this can be the most thought-provoking information and can bring your users to life for stakeholders, it should not be the only data you report. Stakeholders who are eager for immediate results can read the summary worksheets and know what the key points are from each visit. They will appreciate being kept in the loop and will be less likely to insist on being present at each site if they feel you are promptly providing the information.

The template should be flexible enough so that you can record data you hadn’t anticipated and avoid losing important insights. You may also further develop the template as you conduct more visits. Just make sure that everyone who views the summaries understands that they are viewing summary data from one data point. They should not begin building the product or making changes to their existing product based on their interpretations of that data.

Create any incident diaries, surveys, prototypes, or interview worksheets you may need during your study. You can also create any pre-visit activity materials such as mailing out a survey in advance to help you develop your observation guide. Incident diaries are another valuable tool to send out prior to your visit. The surveys and diaries will be extremely useful if you know you will have limited time with each participant.

Summary

We have provided a lot of information to help you prepare for your field study. Figure 13.8 now summarizes the main points. Use this checklist when preparing for your study.

Conducting a Field Study

The specific procedure for your field study will obviously vary depending on the type of study you conduct. We can offer some high-level tasks to conduct, regardless of the type of study. Just remember to remain flexible.

Get Organized

If the visit has been arranged (i.e., this is not a public location where you can observe users unnoticed), upon arrival meet with your site contact. Familiarize yourself with the environment. Where is the bathroom, kitchen, copier, etc.? Where can you get food (if that hasn’t been planned for you already)? If your site contact won’t be with you throughout the visit, how will you get to your next appointment, and so forth? If there are multiple investigation teams, decide where and when you will meet up again. Arrive at least 15 minutes before your first scheduled appointment to take care of these details. Be prepared for some extra hand-shaking and time at this point. You may need to say “hello” to the contact’s or user’s boss. This is another good reason for being early.

Meet the Participant