Coping with Political and Economic Risks

Overview

We hope we have adequately conveyed that diversification in global trading benefits international business investments, especially in emerging markets, which have become a prominent feature of the financial globalization sweeping the world over the last decade. Investing in emerging markets, however, exposes companies and investors to political environments that are not typically present in advanced economies.

Over the past two decades, we have witnessed Russian default on its debt to foreigners in 1998, the Mexican peso crisis in 1994, and the Asian economic meltdown in 1997. While these risks are usually well known to major banks and multinational companies, and assessment techniques in these domains are relatively well developed, they tend not to be appropriate in assessing the geopolitical aspects associated with cross country correlations.

Political risks for FDI are affected when difficult to anticipate discontinuities resulting from political change occur in the international business environment. Some example include the potential restrictions on the transfer of funds, products, technology and people, uncertainty about policies, regulations, governmental administrative procedures, and risks on control of capital such as discrimination against foreign firms, expropriation, forced local shareholding, and so on. Wars, revolutions, social upheavals, strikes, economic growth, inflation and exchange rates should also be figured into the political and economic risk assessment, as these instances can negatively impact local investments as well as FDI.

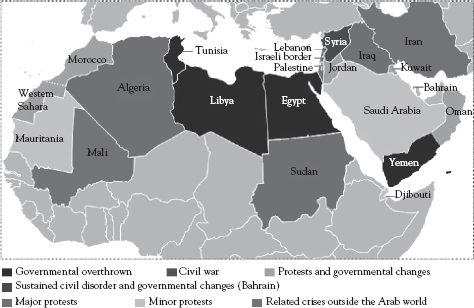

Conducting business internationally, therefore, may offer many opportunities, but not without risks, especially political ones. There have been a myriad of events occurring around the world in the past three years, particularly among emerging economies, more notably the MENA region, as depicted in Figure 13.1. For instance, a revolutionary wave of demonstrations and protests, riots, and civil wars in the Arab world began in early December 2010. Its effects are still lingering. As of November 2013, rulers from this region have been forced from power, as in Tunisia,1 which took down the country’s long-time dictator, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. At the time, many were looking to it as a turning point for the Arab world, and rampant speculation about what it could mean for other countries toiling under Islamic dictatorships.

Although the Arab Spring began in Tunisia, the decisive moment that changed the Arab region forever was the downfall of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who ensconced in power since 1980. Similar to Tunisia, mass protests started in late January of 2011 and by early February Mubarak was forced to resign after the military refused to intervene against the masses occupying Tahrir Square in Cairo. Deep divisions emerged over the new political system as Islamists from the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) won the parliamentary and presidential election in 2011/12 souring relations with secular parties that continued protests for deeper political change. The Egyptian military remains the single most powerful political player, and much of the old regime remains in place. The economy has been in decline since the start of unrest.2

Figure 13.1 Several political conflicts affected MENA economies in the past three years

By the time Mubarak resigned, large portions of the Middle East were already in turmoil. Soon after Mubarak’s resignation, in February 2011, protests against Col. Muammar al-Qaddafi’s regime in Libya started, escalating into the first civil war caused by the Arab Spring. NATO3 forces had to intervene in March 2011 against Qaddafi’s army, helping the opposition rebel movement to capture most of the country by August 2011. In October 2011 Qaddafi was killed, but the rebels’ coup was short-lived, as various rebel militias effectively partitioned the country among them, leaving a weak central government that continues to struggle to exert its authority and provide basic services to its citizens. Most of the oil production has returned on stream, but political violence remains endemic, and religious extremism has been on the rise*

From Libya, the Arab Spring blew toward Yemen. Bolstered by events in Tunisia, anti-government protesters of all political parties started pouring onto the streets in mid-January 2011. Hundreds of people died in clashes as pro-government forces organized rival rallies, and the army began to disintegrate into two political camps. As a result, the Yemeni leader, Ali Abdullah Saleh, became the fourth victim of the Arab Spring. Amidst all this turmoil, Al Qaeda in Yemen began to seize territory in the south of the country. Had it not been for Saudi Arabia’s facilitation of a political settlement Yemen would have fallen victim to an all-out civil war. President Saleh signed the transition deal on November 23, 2011, agreeing to step aside for a transitional government led by the Vice-President Abd al-Rab Mansur al-Hadi. However, little progress toward a stabile democratic order has been made and regular Al Qaeda attacks, separatism in the south, tribal disputes, and a collapsing economy, all stall this nascent transition.4

Many Arab Spring demonstrations have been met with violent responses from authorities, as well as from pro-government militias and counter-demonstrators. These attacks have been answered with violence from protestors in some cases. A major slogan of the demonstrators in the Arab world has been Ash-sha’b yurid isqat an-nizam (“the people want to bring down the regime”).5 Hence, at the same time Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya were dealing with the consequences of the Arab Spring, civil uprisings were also breaking out in Bahrain and Syria, while several major protests continued to erupt in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, and Sudan.

Protests in Bahrain began on February 2012, just days after Mubarak’s resignation. Bahrain has always had a long history of tension between the ruling Sunni royal family, and the majority Shiite population demanding greater political and economic rights. The Arab Spring acted as a catalyst, reenergizing the largely Shiite protest movement, driving tens of thousands to the streets defying fire from security forces. The Bahraini royal family was saved by a military intervention of neighboring countries led by Saudi Arabia. A political solution, however, was not reached and the crackdown failed to suppress the protest movement. As of early fall 2013, protests, clashes with security forces, and arrests of opposition activists continue in that country with no solution in sight.6

Syria, a multi-religious country allied with Iran, ruled by a repressive republican regime, and amid a pivotal geo-political position was next. The major protests began in March 2011 in provincial towns at first, but gradually spreading to all major urban areas. The regime’s brutality provoked an armed response from the opposition, and by mid-2011 army defectors began organizing in the Free Syrian Army. Consequently, by the end of 2011, Syria slid into an obstinate civil war, which is still ongoing today, with most of the Alawite* religious minority siding with President Bashar al-Assad, and most of the Sunni majority supporting the rebels. Both camps have outside backers. Russia supports the regime, while Saudi Arabia supports the rebels with neither side able to break the deadlock.7

On February 20, 2011, the Arab Spring engulfed Morocco, when thousands of protesters gathered in the capital city, Rabat demanding greater social justice and limits to King Mohammed VI’s power. The king responded by offering constitutional amendments ceding some of his powers, and by calling a fresh parliamentary election controlled less by the royal court than in previous elections. This, together with fresh state funds to help low-income families, diminished the appeal of the protest movement, with many Moroccans content with the king’s program of gradual reform. Rallies demanding a genuine constitutional monarchy continue, but have so far failed to mobilize the masses as it did in Tunisia and Egypt.8

Demonstrations in Jordan gained momentum in late January 2011, as Islamists, leftist groups, and youth activists protested against living conditions and corruption. Parallel to Morocco, most Jordanians wanted to reform, rather than abolish the monarchy, giving King Abdullah II the breathing space his republican counterparts in other Arab countries didn’t have. Consequently, the king managed to ease the Arab Spring by making superficial changes to the political system and reorganizing the government. Fear of chaos similar to Syria did the rest. To date, the economy, however, is still performing poorly and none of the key issues have been addressed, which may prompt protesters’ demands to grow more radical over time.9

Algerian protests, which started in late December 2010, were inspired by similar protests across the MENA region. Causes included unemployment, the lack of housing, food-price inflation, corruption, restrictions on freedom of speech, and poor living conditions. While localized protests were already commonplace in previous years, extending into December 2010, an unprecedented wave of simultaneous protests and riots, sparked by a sudden rise in staple food prices, erupted all over the country beginning in January 2011. These protests were suppressed by government swiftly lowering food prices, but were followed by a wave of self-immolations, most of which occurred in front of government buildings. Despite being illegal to do so without government permission, opposition parties, unions, and human rights groups began holding weekly demonstrations. The government’s reaction was a swift repression of these demonstrations.10

The 2011 Iraqi protests came in the wake of the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. The protests have resulted in at least 45 deaths, including at least 29 on the Day of Rage, which took place on February 25, 2011. Several of the protests in March 2011, however, were against the Saudi-led intervention in Bahrain.11 Protests also took place in Iraqi Kurdistan, an autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq’s north that lasted for 62 consecutive days. More recently, on December 21, 2012, a group raided Sunni Finance Minister Rafi al-Issawi’s home and resulted in the arrest of 10 of his bodyguards.12 Beginning in Fallujah, the protests have since spread throughout Sunni Arab parts of Iraq, and have even gained support from non-Sunni Iraqi politicians, such as Muqtada al-Sadr. Pro-Maliki protests have taken place throughout southern Iraq, where there is a Shia Arab majority. In April 2013, sectarian violence escalated after the 2013 Hawija clashes.13

Kuwaiti protests took place in 2011–2012, also calling for government reforms. On November 28, 2011, the government of Kuwait resigned in response to the protests, making Kuwait one of several countries affected by the Arab Spring to experience major governmental changes due to unrest.14

As part of the Arab Spring, protests in Sudan began in January 2011 with a regional protest movement. Unlike other Arab countries, however, popular uprisings in Sudan succeeded in toppling the government prior to the Arab Spring, in both 1964 and 1985. Demonstrations were less common throughout the summer of 2011, during which time South Sudan seceded from Sudan. It resumed in force in June 2012 shortly after the government passed its much criticized austerity plan.15

There have been other minor protests, which broke out in Mauritania, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, and West Sahara. In Mauritania,16 the protests were largely peaceful, demanding President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz to institute political, economic, and legal reforms. The common themes of these protests included slavery, which officially is illegal in Mauritania, but is widespread in the country,17 and other human rights abuse the opposition had accused the government of perpetrating. These protests started in January 2011 and continued well into 2012. In Oman,18 demonstrations were demanding salary increases, increased job creation, and fighting corruption. The sultan’s responses included dismissal of one third of his government cabinet.19 In Saudi Arabia,20 the protests started with a self-immolation in Samtah and demonstration in the streets of Jeddah in late January 2011. It was then followed by protests against anti-Shia discrimination in February and early March of the same year in Qatif, Hofuf, al-Awamiyah, and Riyadh. In Djibouti,21 the protests, which showed a clear support of the Arab Spring, ended quickly after mass arrests and exclusion of international observers. Lastly, in Western Sahara,22 the protests were a reaction to the failure of police to prevent anti-Sahrawi looting in the city of Dakhla, Western Sahara, and mushroomed into protests across the territory. They were related to the Gdeim Izik protest camp in Western Sahara, established the previous fall, which had resulted in violence between Sahrawi activists and Moroccan security forces and supporters.

Still, there were other related events outside of the region. In April 2011, also known among protesters as the Ahvaz Day of Rage, protests occurred in Iranian Khuzestan by the Arab minority. These violent protests erupted on April 15, 201123 marking the anniversary of the 2005 Ahvaz unrest. These protests lasted for four days and resulted in about a dozen protesters killed and many more wounded and arrested. Israel also experienced its share of political conflicts with border clashes in May 2011,24 to commemorate what the Palestinians observe as Nakba Day. During the demonstrations, various groups of people attempted to approach or breach Israel’s borders from the Palestinian-controlled territory, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, and Jordan.

Assessing Political Risks

As barriers to international trade easel, the dynamic global marketplace continues to attract investors who are eager to capitalize on opportunities they see in emerging markets around the world. Compared to a quarter century ago, these markets enjoy greater stability and are experiencing steady growth. However, these emerging markets remain vulnerable to a host of forces known as political risk that are largely beyond the control of investors. Among these risk factors are currency instability, corruption, weak government institutions, unreformed financial systems, patchy legal and regulatory regimes, and restrictive labor markets.

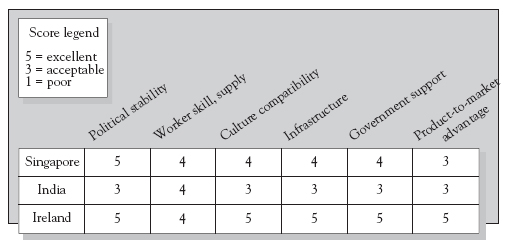

Assessment techniques for political risk are as wide-ranging as the sources that generate it. Traditional methods for assessing political risk range from the comparative techniques of rating and mapping systems, as depicted in Figure 13.2, to the analytical techniques of special reports, dynamic segmentation, expert systems, and determination to the econometric techniques of model building and discriminant and logit analysis.* These techniques are very useful for identifying and analyzing individual sources of political risk but aren’t sophisticated enough to handle cross relationships or correlations well. They also are not accurate measurements of levels of loss generated by the risks being analyzed. Hence, it is difficult to evaluate country profiling and analysis into a practical decision making tool.

In Dr. Goncalves’ lectures at Nichols College, when analyzing the inter-dynamics of advanced economies and emerging markets, two approaches are used for incorporating political risk in the capital budgeting process for foreign direct investments. The first approach involves an ad hoc adjustment of the discount rate to account for losses due to political risk, while the second approach involves an ad hoc adjustment of the project’s expected future cash flows and expected return on investment (ROI).

No company, domestic or international, large or small, can conduct business abroad without considering the influence of the political environment in which it will operate. One of the most undeniable and crucial realities of international business is that both host and home governments are integral partners. A government controls and restricts a company’s activities by encouraging and offering support or by discouraging and restricting its activities contingent upon the whim of the government.

International law recognizes the sovereign right of a nation to grant or withhold permission to do business at the privileges of the government. In addition, international law recognizes the sovereign right of a nation to grant or withhold permission to do business within its political boundaries and to control where its citizens conduct business.

In the context of international law, a sovereign state is independent and free from all external control; enjoys full legal equality with other states; governs its own territory; selects its own political, economic, and social systems; and has the power to enter into agreements with other nations. Sovereignty refers to both the powers exercised by a state in relation to other countries and the supreme powers exercised over its own members. A state outlines and decides the requirements for citizenship, defines geographical boundaries, and controls trade and the movement of people and goods across its borders.

Nations can and do abridge specific aspects of their sovereign rights in order to coexist with other nations. The European Union, UN, NAFTA, NATO, and WTO represent examples of nations voluntarily agreeing to succumb some of their sovereign rights in order to participate with member nations for a common, mutually beneficial goal. However, U.S. involvement in international political affiliations is surprisingly low. For example, the WTO is considered by some as the biggest threat, thus far to national sovereignty. Adherence to the WTO inevitably means loss to some degree of national sovereignty because member nations have pledged to abide by international covenants and arbitration procedures. Sovereignty was one of the primary issues at the core of a kerfuffle between the United States and the EU over Europe’s refusal to lower tariffs and quotas on bananas. Critics of the free trade agreements with both South Korea and Peru claim America’s sacrifice of sovereignty goes too far.

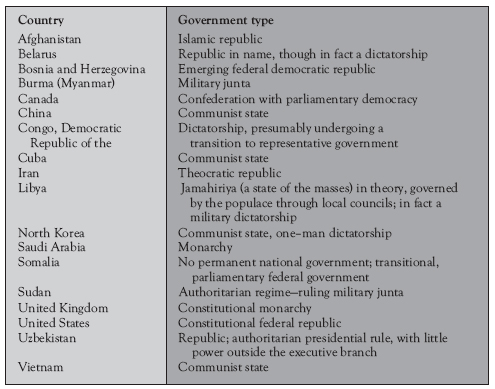

Figure 13.3 provides a sampling of countries electing other options including authoritarianism, theocracy, dictatorship, and communism, which are taking different approach. Troubling is the apparent regression of some countries toward autocracy and away from democracy, such as Nigeria, Kenya, Bangladesh, Venezuela, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan. It is transparent for all to witness the world’s greatest experiment in political and economic change—the race between Russian reforms and Chinese gradualism as communism is left further behind in both countries.

Economic and cultural nationalism, which exists to some degree within all countries, is another important risk factor when assessing the international business environment. Nationalism can best be described as an intense feeling of national pride and unity. One of the economic nationalism’s central aims is the preservation of economic autonomy whereby residents identify their interests with that preservation of the sovereignty. Hence, national interests and security become far more important than international business relations.

Generally, the more a country feels threatened by some outside force or a decline in domestic economy is evident, the more nationalistic it becomes in protecting itself against intrusions. By the late 1980s, militant nationalism had subsided. Today, the foreign investor, once feared as a dominant tyrant threatening economic development, is often sought after as a source of needed capital investment. Nationalism vacillates as conditions and attitudes change, and foreign companies welcomed today may be harassed tomorrow.

It is important for international business professionals not to confuse nationalism, whose animosity is directed generally toward all foreign countries, with a widespread fear directed at a particular country. Toyota committed this mistake in the United States during the late 1980s and early 1990s. At the time Americans considered the economic threat from Japan greater than the military threat from the Soviet Union. So when Toyota spent millions on an advertising campaign showing Toyotas being made by Americans in a plant in Kentucky, it exacerbated the fear that the Japanese were “colonizing” the United States. The same sentiments ring true with China, who some believe, is colonizing the United States.25

The United States is not immune to these same types of directed negativity. The rift between France and the United States over the Iraq–U.S. war led to hard feelings on both sides and an American backlash against French wine, French cheese, and even products Americans thought were French. French’s mustard felt compelled to issue a press release stating that it was an American company founded by an American named French. Thus, it is quite clear that no nation-state, however secure, will tolerate penetration by a foreign company into its market and economy if it perceives a social, cultural, economic, or political threat to its well-being.

Various types of political risks should be considered before investing in foreign markets, for both advanced and emerging economies. The most severe political risk is confiscation, that is, the seizing of a company’s assets without payment. The two most notable recent confiscations of U.S. property occurred when Fidel Castro became the leader in Cuba and later when the Shah of Iran was overthrown. Confiscation was most prevalent in the 1950s and 1960s, when many underdeveloped countries saw confiscation, albeit ineffective, as a means of economic growth.

Less drastic, but still severe, is expropriation, when the government seizes an investment but some reimbursement for the assets is made. Often the expropriated investment is nationalized, that is, it becomes a government-run entity. An example is Bolivia, where the president, Ivo Morales, confiscated Red Eletrica, a utility company from Spain.

Figure 13.4 Country ranking by political and operating risks

Note: *Out of 100, with higher numbers indicating more risk.

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit

A third type of risk is domestication. This occurs when host countries gradually induce the transfer of foreign investments to national control and ownership through a series of government decrees by mandating local ownership and greater national involvement in a company’s management. Figure 13.4 provides a sample list of country rankings in terms of political risks when operating a business.

Even though expropriation and confiscation are waning, international companies are still confronted with a variety of economic risks that can occur with little warning. Restraints on business activity may be imposed under the banner of national security to protect an infant industry, to conserve scarce foreign exchange, to raise revenue, or to retaliate against unfair trade practices. Following are important and recurring reality of economic risks, and recurring of the international political environment, that few international companies can avoid:

•Exchange control—These stem from shortages of foreign exchange held by a country.

•Import restrictions—These are selective restrictions on the import of raw materials, machines, and spare parts; fairly common strategies to force foreign industry to purchase more supplies within the host country and thereby create markets for local industry.

•Labor problems—In many countries, labor unions have strong government support that they use effectively in obtaining special concessions from business. Layoffs may be forbidden, profits may have to be shared, and an extraordinary number of services may have to be provided.

•Local-content laws—In addition to restricting imports of essential supplies to force local purchase, countries often require a portion of any product sold within the country to have local content, that is, to contain locally made parts.

•Price controls—Essential products that command considerable public interest, such as pharmaceuticals, food, gasoline, and cars are often subjected to price controls. Such controls applied during inflationary periods can be used to control the cost of living. They also may be used to force foreign companies to sell equity to local interests. A side effect could be slowing or even halting capital investment.

•Tax controls—Taxes must be classified as a political risk when used as a means of controlling foreign investments. In such cases, they are raised without warning and in violation of formal agreements.

Boycotting is another risk, whereby one or a group of nations might impose it on another, using political sanctions, which effectively stop trade between the countries. The United States has come under criticism for its demand for continued sanctions against Cuba and its threats of future sanctions against countries that violate human rights issues. History, however, indicates that sanctions are almost always unsuccessful in reaching desired goals, particularly when other nations’ traders ignore them.

International business professionals traveling to emerging markets or even, to the so-called least develop countries (LDCs), must be aware of any travel warnings related to political, health, or terrorism risks. The U.S. Department of State (DOS) provides country specific information for every country. For each country, there is information related to location of the U.S. embassy or consular offices in that country, whether a visa is necessary, crime and security information, health and medical conditions, drug penalties, and localized hot spots. This is an invaluable resource when assessing country risks.

The DOS also issue travel alerts for short-term events important for travelers when planning a trip abroad. Issuing a travel alert might include an election season that is bound to have many strikes, demonstrations, disturbances; a health alert like an outbreak of H1N1; or evidence of an elevated risk of terrorist attacks. When these short-term events conclude, the DOS cancels the alert.

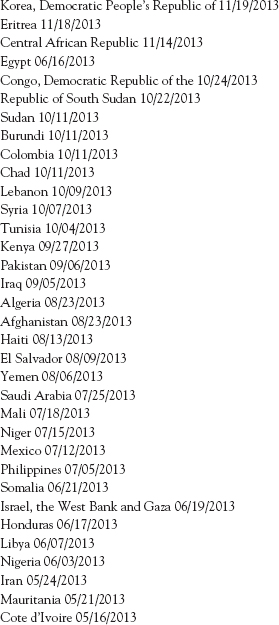

Travel warnings are more important as the DOS issues them when it wants travelers to consider carefully whether to enter into the country at all. Reasons for issuing a travel warning might include an unstable government, civil war, ongoing intense crime or violence, or frequent terrorist attacks. The U.S. government wants international travelers to know the risks of traveling to these places and to strongly consider not going at all. These travel warnings remain in place until the situation changes; although some have been in effect for years. They are often issued when long-term, protracted conditions lead the State Department to recommend Americans avoid or consider the risk of travel to that country. A travel warning* also is issued when the U.S. government’s ability to assist American citizens is constrained due to the closure of an embassy or consulate, or because of a drawdown of its staff. As of fall 2013, the countries listed in Figure 13.5 meet those criteria.

Figure 13.5 List of countries in the U.S. Department of State travel-warning list as of fall 2013

Source: U.S. Department of State

Managing Political Risk

Elisabeth Boone, chartered property casualty underwriter (CPCU) and manager of political risk and credit at ACE Global Markets,26 argues that very few companies actually have a formal approach to risk management when it comes to emerging markets. She indicates that although the great majority of companies she surveys and advises are aware that political risk management is important to their operations, just 49 percent of them integrate it formally into their investment process, while 41 percent take an informal approach to considering political risk as part of their investment process. This gap between awareness of political risk and formal action to manage it, Boone argues, is serious cause for concern given the fact that 79 percent of her survey respondents reported that their investments in emerging markets had increased over the past three years.

Not surprising, in the post-9/11 era is another survey finding that Boone deems noteworthy. She argues that there is “a perception that terrorism is a greater or at least an equal risk to U.S. assets as political risk, but if you look at the severity of what a confiscation would do to your balance sheet, I believe you’d want to consider political risk as an equal or greater threat in terms of lost investments.”

Indeed, as discussed earlier, in some emerging markets governments seize foreign assets wholesale. In other areas they go after entire sectors. According to Boone, “We’re seeing that in mining, oil and gas, and telecommunications. So it’s not that they get one of your facilities; they take the whole thing. If you couple that risk with the fact that you don’t have an actual risk management process in place, the question becomes: What do you do if you’re hit?”

With emerging markets in every corner of the globe, some challenges for international business professionals and investors are bound to be specific to a particular country or political system. To answer the question of how to manage emerging market risk, you first have to define what is emerging market risk. Essentially, it’s volatility and uncertainty. Again, according to Boone, if “you’re in a place where there are unstable political, social, and economic conditions, are you able to clearly identify the risks? And if you have identified them, do you have a backup plan for how to respond to a crisis when it happens?” Once you’ve made that investment you have to continue to monitor and manage the risk.

When considering emerging markets you must find ways to manage risks introduced by unstable and less predictable governments. International business professionals and investors may be faced with an uncertain legal environment, environmental and health care issues, volatile employment and labor relations, and the involvement of NGOs (nongovernmental organizations). It is important to consider reputational risk as well; being targeted by companies or countries for any reason.

There are a few great companies, such as ACE Global Markets,27 that cover emerging market risks and focus on three areas: political insurance, trade credit, and trade credit insurance. First is political risk insurance, where they cover investments and trade by addressing confiscation of assets as well as interruption of trade in emerging markets due to political events. They also manage structured trade credit, short and medium term, and offer trade credit insurance.

* North Atlantic Treaty Organization, an international organization composed of the Unites States, Canada, UK, and a number of European countries for purposes of collective security.

* Member of a Shiite Muslim group living mainly in Syria.

* Logit analysis is a statistical technique used by marketers to assess the scope of customer acceptance of a product, particularly a new product. It attempts to determine the intensity or magnitude of customers’ purchase intentions and translates that into a measure of actual buying behavior.

* Such information changes often, so we advise you to check the website for up-to-date information at http://travel.state.gov/travel/travel_1744.html, last accessed on 10/10/2013.