Introduction: Pensions Are Dying; Long Live Pensions

“...At present, the only way a company can manage the risk of long-lived workers is to work them so hard that they die within a few years of retirement; this is not a good way to retain staff....”

Financial Times, editorial, September 30, 2006

On Wednesday, August 25, 2010, construction giant, Caterpillar Inc., issued a press release that was distributed to newswires and the usual business channels. In a briefly worded statement, it announced that all management, support, and other nonunion employees in the U.S. would no longer be entitled to participate in the company’s traditional pension plan. The plan was being closed and frozen to all nonunion employees. Instead, new Caterpillar employees would be given the option of participating in the company’s enhanced salary-deferred, tax-sheltered savings program, also known as a 401(k) plan. Employees who elected to join the 401(k) plan would have their contributions or savings matched by Caterpillar, up to a limit, as is usually the case with these ubiquitous plans. They would be given the ability to manage and diversify their investments across a wide range of stocks, bonds, and other funds. In a sense, they would all become personal pension fund managers.

In the technical language of pension economics, Caterpillar had replaced its guaranteed defined benefit (DB) pension plan with a defined contribution (DC) pension plan. Like many other companies before it, and many others since, Caterpillar “threw in the towel” and went from DB to DC.

Hundreds of companies have made the same move as Caterpillar in the last few years, and most of them have been cheered on by the market. Major corporations are basically moving away from providing pension income for life. They are shifting the responsibility to you personally. This is why it is now more important than ever for you to answer this question: Are you a stock or a bond?

How Do Pensions Work, Exactly?

At its essence, a traditional defined benefit (DB) pension plan is the easiest way of generating and sustaining a retirement income. When you retire from a DB plan, the employer via the pension plan administrator uses a simple formula to determine your pension entitlement. He adds up the number of years you have been working at the company—for example, 30 years—and multiplies this number by an accrual rate—for example, 2%. The product of these two numbers is called your salary replacement ratio, which in the preceding example is 2% × 30 = 60%. Therefore, your annual pension income, which you will receive for the rest of your life as long as you live, is 60% of your annual salary measured on or near the day you retired. In the preceding case, if you retired at a salary of $50,000 per year, your pension would be 60% of that amount, which is $30,000 of pension income as long as you live.

Now sure, a number of DB pension plans have slightly more complicated formulas that are used to arrive at your pension income entitlement. The accrual rate of, say, 2% might vary depending on when you joined the plan, how much you earn, and perhaps even your age. In some cases an average of your salary in the last few years or perhaps your best year’s salary is used for the final calculation. Some pension plans adjust your annual pension income every year by inflation, whereas others don’t, which then results in the declining purchasing power of retirees over time. Nevertheless, regardless of the minutia, your initial income under a DB pension plan is computed by multiplying three different numbers together. The first number is the accrual rate, the second number is the number of years you have been part of the pension plan, and the third number is your final salary, or the average of your salary during the last few years of employment. Hence, the term defined benefit. Here is the key point: You know exactly what your income benefit will be as you get closer to the golden years. This knowledge provides certainty, tranquility, and predictability. This arrangement was the norm for most large North American companies and their employees for more than 50 years. In fact, the earliest corporate defined benefit pension plans have more than a 100-year history.

A defined contribution (DC) plan is the exact opposite of a DB plan and is a broad term that includes self-directed accounts such as 401(a), 401(k), and 403(b) plans. (In Canada they are known as Group RRSPs, or Capital Accumulation Plans.) Regardless of the exact name, in these plans there is no guaranteed benefit, or for that matter, any guarantee at all regarding pension income. As the name implies, only the contributions are known and determined in advance. The future benefit that you will receive upon entering retirement is completely unknown. If the stock market, or the particular mutual fund in which your money is allocated, experiences a bad month, year, or decade around the time of your retirement, then your nest egg will be much smaller. Anyone who retired around the financial crisis period 2007 to 2008 knows exactly what I mean by “bad timing.” In general, the responsibility, risk, and yes, the possible rewards, are in the hands of the employee as opposed to employer.

Once again, DC plans contain no formulas or income guarantee. In fact, they don’t really focus on retirement income at all. They are salary-deferred, tax-sheltered savings plans, where you and your employer contribute a periodic amount. Your final retirement nest egg will depend on how much you (and/or the company) contribute to the plan, how your investments perform on the way to retirement, and what you do with the money when you retire. A 401(k) is a number, not a pension. The amount of money in your 401(k) plan, at the time you retire, is unknown and unpredictable in advance. In the language of probability theory, it is a random number. Indeed, you might experience a bear market just before your retirement date, and the nest egg might lose 20% to 30% of its value, as most plans did during the bear market of 2008 to 2009. The 401(k) plan is, therefore, not a pension. You, the retiree, have to figure out how to convert this into some sort of pension—similar to the defined benefit pension described previously—as you transition into retirement.

I don’t mean to single out Caterpillar, because it is not the only company taking the DC course of action. Indeed, missing the evidence of the decline of traditional private-sector DB pensions is difficult. Countless company press releases, government studies, and scholarly reports have been documenting that DB plans are being frozen, replaced, and converted into DC plans such as 401(k), 403(b), and other hybrid structures. This is the new reality of personal finance. The responsibility is shifting to you.

The Continued Decline of DB Plans

Companies such as Boeing (January 2009), Anheuser-Busch (April 2009), Wells Fargo (July 2009), the New York Times (January 2010), Sunoco (June 2010), General Electric (December 2010), and McGraw-Hill (April 2012) have all taken actions similar to Caterpillar’s. These companies—and many more—no longer offer a traditional defined benefit pension to their new employees. In many cases, they have frozen or terminated the pension accruals for existing employees as well as new employees, which means that even current members of the pension plan will no longer be entitled to any more credit-years beyond those they have already accrued.

This isn’t a result of the recent crises or the Great Recession. A 2006 survey by the Employee Benefits Research Institute (EBRI) claimed that one-third of all pension plan sponsors in the U.S. with “open” plans—that is, pension plans that still accept new members—were thinking about freezing their DB plan in the next few years. From a different perspective, according to Towers Watson, way back in 1985 a total of 89 out of the largest 100 companies in the U.S. offered a traditional DB pension to their newly hired employees. The vast majority offered traditional pensions. By 2002, this number dropped to 49 out of 100 companies, and in 2010 it was down to 17 out of 100. My hunch is that when the 2012 figures are released, this number might be in the single digits.

Let me stress, though, that few of these companies are in any financial distress, contemplating bankruptcy protection, being liquidated, or filing for protection from creditors. Many of the previously listed companies are quite healthy, successful, and growing entities that have decided to simply throw in the towel and abandon DB pensions. Why exactly have they shifted this responsibility to you?

One of the main factors that has been contributing to this accelerating pension trend is something that we actually should all be thankful for—namely good health and increased longevity. We are living much longer than anybody anticipated or planned for when these defined benefit pension plans were originally designed and set up more than 40 years ago.

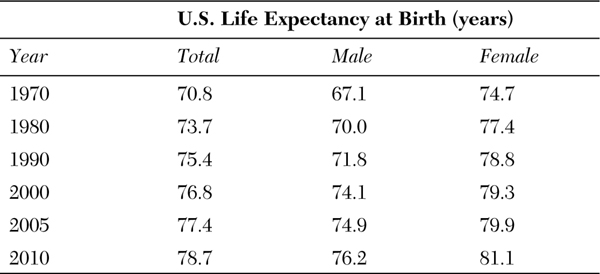

As you can see from Table I.1, back in the 1970s life expectancy (at birth) for the entire U.S. population was approximately 67 years for males and about 75 years for females. The average of the two was slightly below 71 years. However, in the last 40 years this number has marched steadily higher so that by 2010 the average life expectancy was approximately 79 years. This is an 8-year gain within 40 years. Now just think about what life expectancy might look like in 40 or even 80 more years. And that’s not the full story because these numbers only apply at birth. As you age the life expectancy numbers get better, not worse.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, 2010.

A few decades ago, pensions were small sums of money paid for a few years between a formal retirement date and the end of the human lifecycle. But now, this period that was intended and estimated to be 5–10 years is turning into 20 or 30 years. People are retiring earlier (with full benefits) from their pension plan and living into their late nineties.

The resulting pressure on the pension system and plans is an unsupportable retiree-to-active workers ratio. There are just too many retirees and not enough active workers, and therefore not enough revenue to go around to continue to support these payments.

Notice from Table I.2 that the number of retirees per 100 workers is projected to creep up as we move into the middle part of the century. Who will pay for these retirement benefits? How high will these ratios get?

Table I.2. Number of U.S. Retirees Per 100 Workers

Data Source: Social Security Administration, “The 2011 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds,” p. 48.

In the last 10 to 15 years, the U.S. has experienced a remarkable shift in the way retirement is being saved for and financed. A mere 15 years ago, the total percentage of “retirement assets” (broadly defined) sitting within traditional defined benefit (DB) plans was close to 25%, similar to the percentage in defined contribution (DC) plans. Yet, today, the percentage that is comprised of DB plans is less than 15%.

No matter how you look at it, one would be foolish to assume this trend of reduced DB coverage in the private sector will halt or reverse anytime soon. The only question is the magnitude and speed.

In fact, some consumer advocates and free-market economists argue that this trend away from the traditional pension system is actually a positive change. The idea is that the increased flexibility, mobility, and clarity of defined contribution plans are more in line with the needs of today’s more mobile labor force. For this growing group that plans to be with more than one employer over time, the 401(k), or any defined contribution plan for that matter, is the only option.

But, Are the Shareholders Happy?

Using extensive data on pension freezes, I—together with one of my graduate students—found that during the 10-year period from 2001 to 2011, an average of one to two publicly traded companies per month announced intentions to freeze or shut down their DB plan and either replace it with a DC plan or enhance their existing DC plan with better products, more choices, and greater matches. In addition to the companies I mentioned earlier, Kraft, American Airlines, Bank of America, and Walt Disney Co. are just a few of the major household-name companies that announced freezes to their plans between 2010 and 2012. In 2010, I published a study with Keke Song in the Journal of Risk and Insurance, studying the positive impact of pension freezes on financial markets. The bottom line was that over a window of 10 trading days before and after the announcement of a pension freeze or close, the average increase in stock price was approximately 3.96%. Relative to the S&P 500 index (or in risk-adjusted terms), the effect was even greater—approximately 4.2%. If we expand the event window to 20 business days before and 20 business days after, the aforementioned impact increases to almost 7.3% in risk-adjusted returns.

Our hypothesis for the likely reason is the capping of risk and not necessarily the reduction in compensation expenses or costs. Rather, companies have taken this unquantifiable longevity risk off their corporate balance sheet and transferred it to the employees’ personal balance sheets.

I think this further reinforces the important financial fact for twenty-first century retirement planning. Soon, very few groups of new employees entering the labor force will be able to rely on a DB pension plan to provide retirement income. Whether you are on the verge of retiring, or think you are much too young to even think that far into the future, the responsibility of generating income in your retirement will more than likely rest in your hands. As part of your holistic personal risk management strategy, this book will motivate you to start thinking about how you and your loved ones can help convert the 401(k) and the sum of money you have saved in your retirement nest egg into a true pension that provides a retirement income that you can’t outlive.

The Florida Pension Experiment

Public sector employees who are part of state or local government plans are not entirely immune to the trend I’ve described. If you live in Florida, you might know this already. Between mid-2002 and ending in mid-2003, every one of the approximately 625,000 government employees who were members of the state’s pension fund were presented with a unique decision. Basically, each existing and new employee was granted the option to switch from a traditional defined benefit pension plan to a self-managed investment plan. In other words, they could take the lump-sum value of their retirement pension, and instead invest the proceeds themselves in a wide range of carefully vetted mutual funds. Alternatively, they could choose to maintain the status quo and remain in their current traditional defined benefit (DB) pension plan until retirement.

The upside or gain from pension switching was twofold: The employees would be given the chance to manage and invest the money that they have already earned and accrued, and they will be given the opportunity to do the same with any future contributions. Again, this “investment plan” is not a pension plan. It is a tax-sheltered investment account that will (hopefully) grow over time, the investment returns will (hopefully) beat inflation, and the nest egg will provide a nice cushion for their retirement. However, at some point the employee is going to have to turn this money into an actual pension that provides a respectable income for the rest of his retirement.

In fact, both General Motors (GM) and Ford offered the exact same option to many of their employees and retirees. They could keep their pension annuity income or exchange it for a lump-sum. Hundreds of thousands now face the same decision across the country.

So, here are the fundamental questions they faced:

• Would you take a lump sum in lieu of a pension and invest it yourself, together with all the contributions you would receive from your employer over the next 20 years? Or would you say, “No, thanks” to the offer and just wait until retirement and take a pension based on your 35 years of service?

• If you did decide to take the lump sum and invest it yourself, how exactly would you allocate the money over the next 20 years?

Although I don’t live in Florida I, too, face a similar decision at retirement. I am in a defined benefit plan that gives me the option to cash out in retirement and manage the funds myself for the rest of my life. Luckily, I have about 20 years to decide. How about you? Do you think you could manage and invest a nest egg yourself and grow the money to an amount that would generate a greater lifetime income compared to a pension? What if you live much longer than you expected? What if the market declines just when you are about to retire? What if inflation is higher than expected? It’s a tough decision, no question! And yet, if demographics and corporate trends are any indication, many millions of Americans will be making this exact choice over the next 5 to 10 years. They have a number—an amount of money in a tax-sheltered savings account—and must decide how to convert it into a pension.

Agenda for this Book

My objective is to get you to think differently about the many decisions you make on a daily basis, and to highlight the financial and investment aspects of those decisions. The reason this type of thinking has now become more important than ever is precisely because of the very large responsibility that has now shifted into your hands; namely, the concern of creating a sustainable income for the rest of your very long life. My bias, if I do have one, is to move people away from short-term investing-by-speculating to a more prudent long-term investing-by-hedging or investing-by-protecting. What risks do you really face over the long-run of your financial life, and how do you manage all of your economic assets to protect against those risks?

For now, unfortunately, many individuals make financial decisions thinking they can outguess the market, their opponent, or nature. The truth is that few if any of us are endowed with this ability. And although it’s perfectly fine (and fun) to spend a few thousand dollars betting on whether a given penny stock, mutual fund, or economic sector will outperform another penny stock, fund, or sector, this technique is not the way to manage your personal pension, which must last for the rest of your life. I touch upon this theme—call it the “stop speculating and start hedging” theme—in a number of places within the book.

As you contemplate the possibility of a 30-year or possibly longer retirement, starting to think about managing your financial capital more effectively over your lifecycle is very important. This is more than just about creating a pension or sustainable retirement income. It is about proper risk management practiced by major corporations, applied to your personal life. So, the next few chapters will be devoted to personal financial risk management early in life, which can then prepare you for prudent risk management later in life. Of course, on the way to creating a secure pension, I must start by examining precisely how to measure the value of your own net worth. I first introduce you to the concept of human capital and why it is likely the most valuable asset you currently own or have on your personal balance sheet. With that in hand, I then move on to carefully discuss how you should think about risk and return over very long horizons and to understand the role of hedging versus investing or speculating in regards to managing our human capital. Then, after I get the preliminaries out of the way, I discuss how to properly convert and manage the risk of going from a number in your 401(k) or IRA plan to a pension that will last for the rest of your life. With the decline of traditional DB pensions, retirement income planning is more than just having the right mix of investments or saving enough in your 401(k) plan. A large sum of money in an investment plan—however you define large—doesn’t guarantee you a secure retirement. The strategy you employ and the products you purchase with your nest egg will be more important than the size of that nest egg.

Endnotes

The impact of announcing DB freezes and closures on the stock price of the sponsoring company was studied and documented in the article by Milevsky and Song (2010). For a more extensive discussion of some of the concerns or possible problems with 401(k) plans, see Munnell and Sunden (2003). For additional statistics on the extent of a possible retirement income crisis, see Salsbury (2006), and for a more extensive discussion of the public policy implications of entitlement programs, see Kotlikoff and Burns (2004). Also, the edited books by Aaron (1999) and Clark, et al. (2004) contain some very interesting articles and studies on broader aspects of retirement income planning. Lowenstein (2005) has written an excellent article on the demise of DB pensions from a historical and current-events perspective. The collection of articles in Mitchell and Smetters (2003) provides a more academic perspective on the topic. The Towers Watson June 2010 newsletter includes an interesting discussion of retirement plan trends for Fortune 100 Companies. For further information visit the following webpage: http://www.towerswatson.com/assets/pdf/937/Insider_June2010.pdf