Basic Forms of Organizational Structure

Objective 6-4 Explain the differences among functional, divisional, matrix, and international organizational structures and describe the most popular new forms of organizational design.

Organizations can structure themselves in an almost infinite number of ways; according to specialization, for example, or departmentalization, or the decision-making hierarchy. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify four basic forms of organizational structure that reflect the general trends followed by most firms: (1) functional, (2) divisional, (3) matrix, and (4) international.

Functional Structure

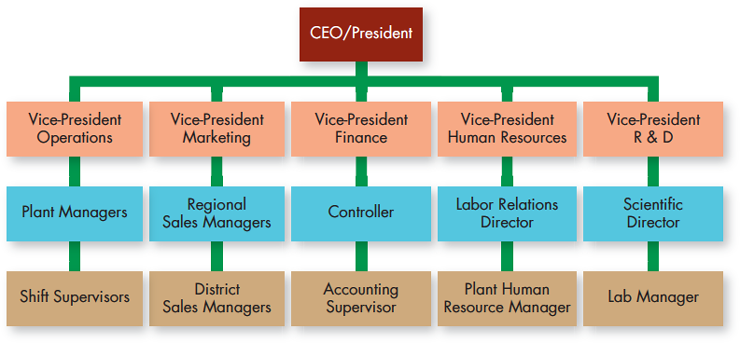

Under a functional structure, relationships between group functions and activities determine authority. Functional structure is used by most small- to medium-sized firms, which are usually structured around basic business functions: a marketing department, an operations department, and a finance department. The benefits of this approach include specialization within functional areas and smoother coordination among them.

In large firms, coordination across functional departments becomes more complicated. Functional structure also fosters centralization (which can be desirable but is usually counter to the goals of larger businesses) and makes accountability more difficult. As organizations grow, they tend to shed this form and move toward one of the other three structures. Figure 6.5 illustrates a functional structure.

Figure 6.5

Functional Structure

Divisional Structure

A divisional structure relies on product departmentalization. Organizations using this approach are typically structured around several product-based divisions that resemble separate businesses in that they produce and market their own products. The head of each division may be a corporate vice-president or, if the organization is large enough, a divisional president. In addition, each division usually has its own identity and operates as a relatively autonomous business under the larger corporate umbrella. Figure 6.6 illustrates a divisional structure.

Figure 6.6

Divisional Structure

Johnson & Johnson, one of the most recognizable names in healthcare products, organizes its company into three major divisions: consumer healthcare products, medical devices and diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals. Each major division is then broken down further. The consumer healthcare products division relies on product departmentalization to separate baby care, skin and hair care, topical health care, oral health care, women’s health, over-the-counter medicines, and nutritionals. These divisions reflect the diversity of the company, which can protect it during downturns, such as the recession in 2008–2010, which showed the slowest pharmaceutical growth in four decades. Because they are divided, the other divisions are protected from this decline and can carry the company through it.

Consider also that Johnson & Johnson’s over-the-counter pain management medicines are essentially competition for their pain management pharmaceuticals. Divisions can maintain healthy competition among themselves by sponsoring separate advertising campaigns, fostering different corporate identities, and so forth. They can also share certain corporate-level resources (such as market research data). However, if too much control is delegated to divisional managers, corporate managers may lose touch with daily operations. Also, competition between divisions can become disruptive, and efforts in one division may duplicate those of another.13

Matrix Structure

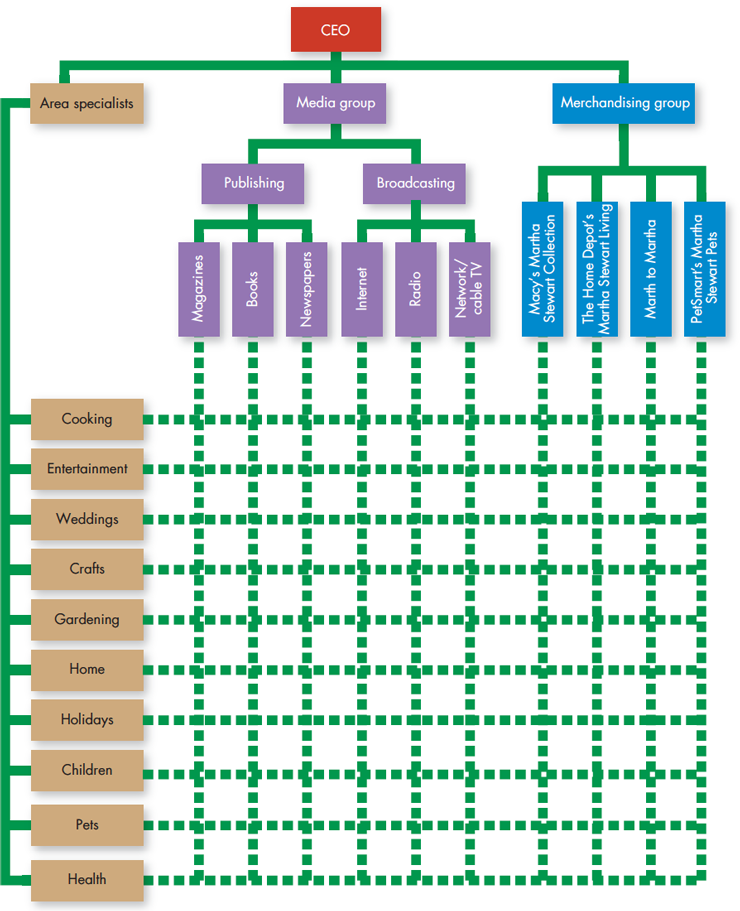

Sometimes a matrix structure, a combination of two separate structures, works better than either simpler structure alone. This structure gets its matrix-like appearance, when shown in a diagram, by using one underlying “permanent” organizational structure (say, the divisional structure flowing up-and-down in the diagram), and then superimposing a different organizing framework on top of it (e.g., the functional form flowing side-to-side in the diagram). This highly flexible and readily adaptable structure was pioneered by NASA for use in developing specific space programs.

Suppose a company using a functional structure wants to develop a new product as a one-time special project. A team might be created and given responsibility for that product. The project team may draw members from existing functional departments, such as finance and marketing, so that all viewpoints are represented as the new product is being developed; the marketing member may provide ongoing information about product packaging and pricing issues, for instance, and the finance member may have useful information about when funds will be available.

In some companies, the matrix organization is a temporary measure installed to complete a specific project and affecting only one part of the firm. In these firms, the end of the project usually means the end of the matrix—either a breakup of the team or a restructuring to fit it into the company’s existing line-and-staff structure. Ford, for example, uses a matrix organization to design new models, such as the 2017 Mustang. A design team composed of people with engineering, marketing, operations, and finance expertise was created to design the new car. After its work was done, the team members moved back to their permanent functional jobs.14

In other settings, the matrix organization is a semipermanent fixture. Figure 6.7 shows how Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia has created a permanent matrix organization for its lifestyle business. As you can see, the company is organized broadly into media and merchandising groups, each of which has specific products and product groups. For instance, there is an Internet group housed within the media group. Layered on top of this structure are teams of lifestyle experts led by area specialists organized into groups, such as cooking, entertainment, weddings, crafts, and so forth. Although each group targets specific customer needs, they all work, as necessary, across all product groups. An area specialist in weddings, for example, might contribute to an article on wedding planning for an Omnimedia magazine, contribute a story idea for an Omnimedia cable television program, and supply content for an Omnimedia site. This same individual might also help select fabrics suitable for wedding gowns that are to be retailed.

Figure 6.7

Matrix Organization of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia

International Structure

Several different international organizational structures are also common among firms that actively manufacture, purchase, and sell in global markets. These structures also evolve over time as a firm becomes more globalized. For example, when Walmart opened its first store outside the United States in 1992, it set up a special projects team. In the mid-1990s, the firm created a small international department to handle overseas expansion. Several years later, international sales and expansion had become such a major part of operations that a separate international division headed up by a senior vice-president was created. International operations have now become so important to Walmart that the international division has been further divided into geographic areas, such as Mexico and Europe. And as the firm expands into more foreign markets, such as Russia and India, new units have been created to oversee those operations.

Some companies adopt a truly global structure in which they acquire resources (including capital), produce goods and services, engage in research and development, and sell products in whatever local market is appropriate, without consideration of national boundaries. Until a few years ago, General Electric (GE) kept its international business operations as separate divisions, as illustrated in Figure 6.8. Now, however, the company functions as one integrated global organization. GE businesses around the world connect and interact with each other constantly, and managers freely move back and forth among them. This integration is also reflected in GE’s executive team, which includes executives from Spain, Japan, Scotland, Ireland, and Italy.

Figure 6.8

International Division Structure

New Forms of Organizational Structure

As the world grows increasingly complex and fast-paced, organizations also continue to seek new forms of organization that permit them to compete effectively. Among the most popular of these new forms are the team organization, the virtual organization, and the learning organization.

Team Organization

Team organization relies almost exclusively on project-type teams, with little or no underlying functional hierarchy. People float from project to project as dictated by their skills and the demands of those projects. As the term suggests, team authority is the underlying foundation of organizations that adopt this organizational structure.

Virtual Organization

Closely related to the team organization is the virtual organization. A virtual organization has little or no formal structure. Typically, it has only a handful of permanent employees, a small staff, and a modest administrative facility. As the needs of the organization change, its managers bring in temporary workers, lease facilities, and outsource basic support services to meet the demands of each unique situation. As the situation changes, the temporary workforce changes in parallel, with some people leaving the organization and others entering. Facilities and the subcontracted services also change. In other words, the virtual organization exists only in response to its own needs. This structure would be applicable to research or consulting firms that hire consultants based on the specific content knowledge required by each unique project. As the projects change, so too does the composition of the organization. Figure 6.9 illustrates a hypothetical virtual organization.

Figure 6.9

The Virtual Organization

Learning Organization

The so-called learning organization works to integrate continuous improvement with continuous employee learning and development. Specifically, a learning organization works to facilitate the lifelong learning and personal development of all of its employees while continually transforming itself to respond to changing demands and needs.

Although managers might approach the concept of a learning organization from a variety of perspectives, the most frequent goals are superior quality, continuous improvement, and performance measurement. The idea is that the most consistent and logical strategy for achieving continuous improvement is to constantly upgrade employee talent, skill, and knowledge. For example, if each employee in an organization learns one new thing each day and can translate that knowledge into work-related practice, continuous improvement will logically follow. Indeed, organizations that wholeheartedly embrace this approach believe that only through constant employee learning can continuous improvement really occur. Shell Oil’s Shell Learning Center boasts state-of-the-art classrooms and instructional technology, lodging facilities, a restaurant, and recreational amenities. Line managers rotate through the center to fulfill teaching assignments, and Shell employees routinely attend training programs, seminars, and related activities.