What Is Money?

Objective 16-1 Define money and identify the different forms that it takes in the nation’s money supply.

If someone asks you how much money you have, do you count the dollar bills and coins in your pockets? Do you include your checking and savings accounts? Do you check your balance in Apple Pay or a similar digital payment option? What about stocks and bonds? Do you count your car? Taken together, the value of all these combined is your personal wealth. Not all of it, however, is “money.” This section considers more precisely what money is and what it does.

The Characteristics of Money

Modern money generally takes the forms of stamped metal or printed paper issued by governments. Theoretically, however, just about anything portable, divisible, durable, and stable can serve as money. To appreciate these qualities, imagine using something that lacks them—for example, a 1,000-pound cow used as a unit of exchange in ancient agrarian economies:

Portability. Try lugging 1,000 pounds of cow from shop to shop. In contrast, modern currency is light and easy to handle.

Divisibility. How would you divide your cow if you wanted to buy a hat, a book, and a new phone case from three different stores? Is a pound of cow head worth as much as a pound of cow leg? Modern currency is easily divisible into smaller parts with fixed values—for example, a dollar for four quarters or ten dimes, but a cow is much harder to divide.

Durability. Your cow will lose value every day (and eventually die). Modern currency, however, neither dies nor spoils, and if it wears out, it can be replaced. It is also hard to counterfeit—certainly harder than cattle breeding.

Stability. If cows were in short supply, you might be able to make quite a deal for yourself. In the middle of an abundant cow year, however, the market would be flooded with cows, so their value would fall. The value of our paper money also fluctuates, but it is considerably more stable and predictable.

Cattle are not portable, divisible, durable, or stable, making them an unsuitable medium of exchange in the modern monetized economy.

Thinkstock Images/Stockbyte/Getty Images

The Functions of Money

Imagine a successful cow rancher who needs a new fence. In a barter economy, one in which goods are exchanged directly for another, he or she would have to find someone who is willing to exchange a fence for a cow (or parts of it). If no fence maker wants a cow, the rancher must find someone else—for example, a wagon maker—who does want a cow. Then, the rancher must hope that the fence maker will trade for a new wagon. In a money economy, though, the rancher would sell his or her cow, receive money, and exchange the money for such goods as a new fence.

Money serves three essential functions:

Money is a medium of exchange. Like the rancher “trading” money for a new fence, money is used to buy and sell things. Without money, we would be bogged down in a system of constant barter.

Money is a store of value. Pity the rancher whose cow gets sick on Monday and who wants to buy some clothes on the following Saturday, by which time the cow may have died and lost its value. In the form of currency, however, money can be used for future purchases and therefore “stores” its value.

Money is a measure of worth. Money lets us measure the relative values of goods and services. It acts as a measure of worth because all products can be valued and accounted for in terms of money. For example, the concepts of $1,000 worth of clothes or $500 in labor costs have universal meaning.

We see, then, that money adds convenience and simplicity to our everyday lives, for consumers and businesses alike. Employees, consumers, and businesses use money as the measure of worth for determining wages and for buying and selling products—everything from ice cream to housing rentals. Consumers with cash can make purchases wherever they go because businesses everywhere accept money as a medium for exchange. And because money is stable, businesses and individuals save their money, trusting that its value will be available for future use.

M-1: The Spendable Money Supply

Of course, for money to serve its basic functions, both buyers and sellers must agree on its value. The value of money, in turn, depends in part on its supply—how much money is in circulation. All else equal, when the supply of money is high its value drops and when the supply of money is low its value increases. (Note that this pattern is consistent with the principles of supply and demand as discussed in Chapter 1 .)

Unfortunately, there is no single measure of the supply of money that all experts accept. The oldest and most basic measure, M-1, counts only the most liquid, or spendable, forms of money—cash, checks, and funds in checking accounts.

Paper money and metal coins are currency (cash) issued by the government and widely used for small exchanges. U.S. law requires creditors to accept it in payment of debts.

A check is essentially an order instructing a bank to pay a given sum to a payee. Checks are usually, but not always, accepted because they are valuable only to specified payees and can be exchanged for cash.

Checking accounts, or demand deposits, are money because their funds may be withdrawn at any time on demand.

Instead of using a modern monetary system, traders like Muhammed Essa in Quetta, Pakistan, transfer funds through handshakes and code words. The ancient system is called hawala, which means “trust” in Arabic. The worldwide hawala system, though illegal in most countries, moves billions of dollars past regulators annually and is alleged to be the system of choice for terrorists because it leaves no paper trail.

Ton Koene/Alamy Stock Photo

These are all non-interest–bearing or low-interest–bearing forms of money. As of January 2017, M-1 in the United States totaled $3.617 trillion.2

M-2: M-1 Plus the Convertible Money Supply

M-2, a second measure of the money supply, is often used for economic planning by businesses and government agencies. M-2 includes everything in M-1 plus other forms of money that are not quite as liquid, for example, short-term investments that are easily converted to spendable forms, including time deposits, money market mutual funds, and savings accounts. Totaling $13.932 trillion in January 2017, M-2 accounts for most of the nation’s money supply.3 It measures the store of monetary value available for financial transactions by individuals and small businesses. As this overall level increases, more money is available for consumer purchases and business investments. When the supply is tightened, less money is available—financial transactions, spending, and business activity slow down.

Unlike demand deposits, time deposits, such as certificates of deposit (CDs), have a fixed term, are intended to be held to maturity, cannot be transferred by check, and pay higher interest rates than checking accounts. Time deposits in M-2 include only accounts of less than $100,000 that can be redeemed on demand, with penalties for early withdrawal. With money market mutual funds, investment companies buy a collection of short-term, low-risk financial securities. Ownership of and profits (or losses) from the sale of these securities are shared among the fund’s investors.

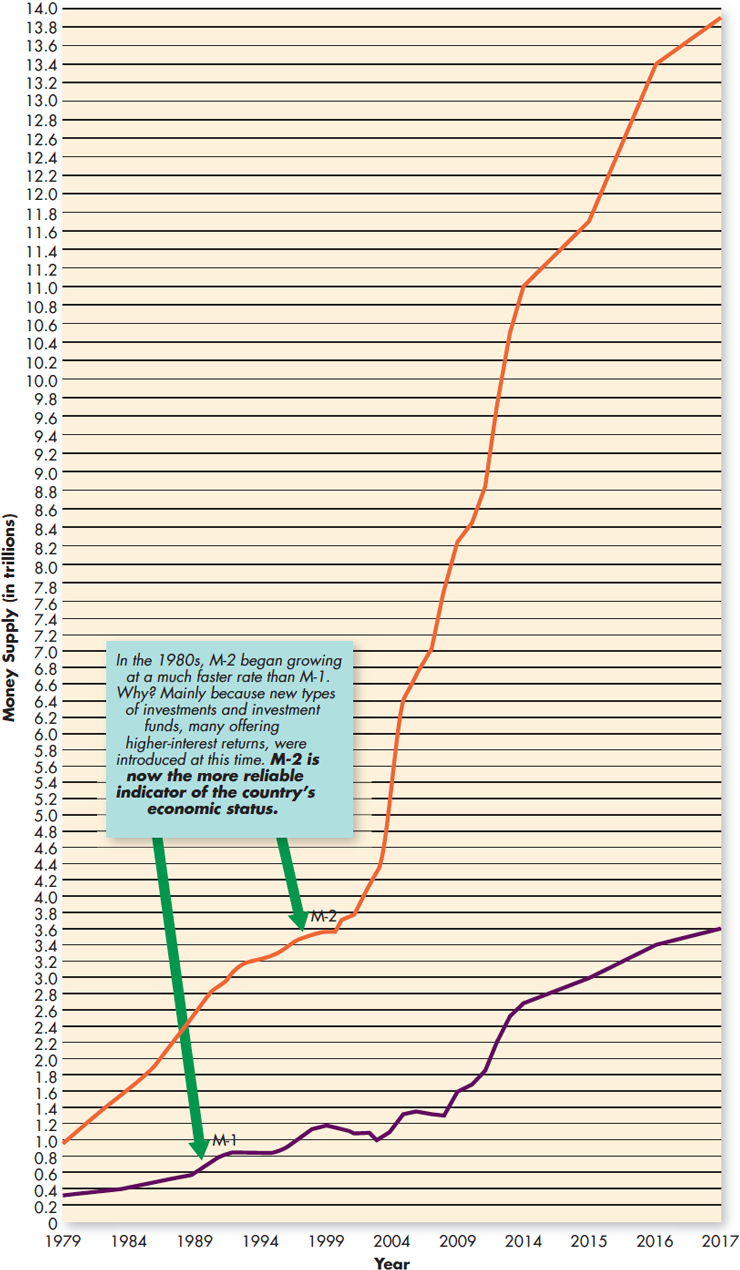

Figure 16.1 shows how M-1 and M-2 have grown since 1979. For many years, M-1 was the traditional measure of liquid money. Because it was closely related to gross domestic product, it served as a reliable predictor of the nation’s real money supply. This situation changed in the early 1980s, with the introduction of new types of investments and the easier transfer of money among investment funds to gain higher interest returns. As a result, most experts today view M-2 as a more reliable measure than M-1.

Figure 16.1

Money Supply Growth

Source: “Money Stock Measures,” Federal Reserve, at www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/current/, accessed on June 1, 2017.

Credit Cards and Debit Cards: Plastic Money?

The use of credit and debit cards has become so widespread that many people refer to them as “plastic money.” Credit cards, however, are not money and, therefore, are not included in M-1 or M-2 when measuring the nation’s money supply. Why? Because spending with a credit card creates a debt, but does not move money until later when the debt is paid by cash or check. Debit card transactions, in contrast, transfer money immediately from the consumer’s bank account, so they affect the money supply the same way as spending with a check or cash, and are included in M-1. Although consumers enjoy the convenience of credit cards, they may also find that irresponsible use of these cards can be hazardous to their financial health. A discussion of managing the use of credit cards is found in Appendix III : Managing Your Personal Finances.