Basic Motivation Concepts and Theories

Objective 8-4 Identify and summarize the most important models and concepts of employee motivation.

Broadly defined, motivation is the set of forces that cause people to behave in certain ways. One worker may be motivated to work hard to produce as much as possible, whereas another may be motivated to do just enough to survive. Managers must understand these differences in behavior and the reasons for them.

Over the years, a steady progression of theories and studies has attempted to address these issues. In this section, we survey the major studies and theories of employee motivation. In particular, we focus on three approaches to human relations in the workplace that reflect a basic chronology of thinking in the area: (1) classical theory and scientific management, (2) early behavioral theory, and (3) contemporary motivational theories.

Classical Theory

According to the classical theory of motivation, workers are motivated solely by money. In his 1911 book, The Principles of Scientific Management, industrial engineer Frederick Taylor proposed a way for both companies and workers to benefit from this widely accepted view of life in the workplace. If workers are motivated by money, Taylor reasoned, paying them more should prompt them to produce more. Meanwhile, the firm that analyzed jobs and found better ways to perform them would be able to produce goods more cheaply, make higher profits, and pay and motivate workers better than its competitors.

Taylor’s approach was known as scientific management. His ideas captured the imagination of many managers in the early twentieth century. Soon, manufacturing plants across the United States were hiring experts to perform time-and-motion studies: Industrial engineering techniques were applied to each facet of a job to determine how to perform it most efficiently. These studies were the first scientific attempts to break down jobs into easily repeated components and to devise more efficient tools and machines for performing them.9 Two of Taylor’s colleagues, Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, wrote a popular book, Cheaper by the Dozen, explaining how they used scientific management to manage their large family. The book was later made into a movie.

Treating employees with respect and recognizing that they are valuable members of the organization can go a long way toward motivating employees to perform at their highest levels.

Ariel Skelley/Blend Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Early Behavioral Theory

In 1925, a group of Harvard researchers began a study at the Hawthorne Works of Western Electric outside Chicago. With an eye to increasing productivity, they wanted to examine the relationship between changes in the physical environment and worker output.

The results of the experiment were unexpected, even confusing. For example, increased lighting levels improved productivity. For some reason, however, so did lower lighting levels. Moreover, against all expectations, increased pay failed to increase productivity. Gradually, the researchers pieced together the puzzle. The explanation lay in the workers’ response to the attention they were receiving. The researchers concluded that productivity rose in response to almost any management action that workers interpreted as special attention. This finding, known today as the Hawthorne effect, had a major influence on human relations theory, although in many cases it amounted simply to convincing managers that they should pay more attention to employees.

Following the Hawthorne studies, managers and researchers alike focused more attention on the importance of good human relations in motivating employee performance. Stressing the factors that cause, focus, and sustain workers’ behavior, most motivation theorists became concerned with the ways in which management thinks about and treats employees. The major motivation theories include the human resources model, the hierarchy of needs model, and two-factor theory.

Human Resources Model: Theories X and Y

In one important book, behavioral scientist Douglas McGregor concluded that managers tended to have had radically different beliefs about how best to use the human resources employed by a firm. He classified these beliefs into sets of assumptions that he labeled “Theory X” and “Theory Y.” The basic differences between these two theories are shown in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1

Theory X and Theory Y

| Theory X | Theory Y |

|---|---|

| People are lazy. | People are energetic. |

| People lack ambition and dislike responsibility. | People are ambitious and seek responsibility. |

| People are self-centered. | People can be selfless. |

| People resist change. | People want to contribute to business growth and change. |

| People are gullible and not bright. | People are intelligent. |

Managers who subscribe to Theory X tend to believe that people are naturally lazy and uncooperative and must be either punished or rewarded to be made productive. Managers who are inclined to accept Theory Y tend to believe that people are naturally energetic, growth-oriented, self-motivated, and interested in being productive.

McGregor argued that Theory Y managers are more likely to have satisfied and motivated employees. Theory X and Y distinctions are somewhat simplistic and offer little concrete basis for action. Their value lies primarily in their ability to highlight and classify the behavior of managers in light of their attitudes toward employees.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Model

Psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs model proposed that people have several different needs that they attempt to satisfy in their work. Maslow classified these needs into five basic types and suggested that they be arranged in the hierarchy of importance, as shown in Figure 8.3. According to Maslow, needs are hierarchical because lower-level needs must be met before a person will try to satisfy higher-level needs.

Figure 8.3

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs

Source: Maslow, Abraham H.; Frager, Robert D.; Fadiman, James, Motivation and Personality, 3rd Ed., © 1987. Adapted and Electronically reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Once a set of needs has been satisfied, it ceases to motivate behavior. For example, if you feel secure in your job (that is, your security needs have been met), additional opportunities to achieve even more security, such as being assigned to a long-term project, will probably be less important to you than the chance to fulfill social or esteem needs, such as working with a mentor or becoming the member of an advisory board.

If, however, a lower-level need suddenly becomes unfulfilled, most people immediately refocus on that lower level. Suppose, for example, you are seeking to meet your self-esteem needs by working as a divisional manager at a major company. If you learn that your division and, consequently, your job may be eliminated, you might well find the promise of job security at a new firm as motivating as a promotion once would have been at your old company.

Two-Factor Theory

After studying a group of accountants and engineers, psychologist Frederick Herzberg concluded that job satisfaction and dissatisfaction depend on two factors: hygiene factors, such as working conditions, and motivation factors, such as recognition for a job well done.

According to Herzberg’s two-factor theory, hygiene factors affect motivation and satisfaction only if they are absent or fail to meet expectations. For example, workers will be dissatisfied if they believe they have poor working conditions. If working conditions are improved, however, they will not necessarily become satisfied; they will simply not be dissatisfied. If workers receive no recognition for successful work, they may be neither dissatisfied nor satisfied. If recognition is provided, they will likely become more satisfied.

Figure 8.4 illustrates the two-factor theory. Note that motivation factors lie along a continuum from satisfaction to no satisfaction. Hygiene factors, in contrast, are likely to produce feelings that lie on a continuum from dissatisfaction to no dissatisfaction. Whereas motivation factors are directly related to the work that employees actually perform, hygiene factors refer to the environment in which they work.

Figure 8.4

Two-Factor Theory of Motivation

This theory suggests that managers should follow a two-step approach to enhancing motivation. First, they must ensure that hygiene factors, such as working conditions or clearly stated policies, are acceptable. This practice will result in an absence of dissatisfaction. Then they must offer motivation factors, such as recognition or added responsibility, as a way to improve satisfaction and motivation.

Other Important Needs

Each theory discussed so far describes interrelated sets of important individual needs within specific frameworks. McClelland’s acquired needs theory hypothesized three other needs: the needs for achievement, affiliation, and power. Most people, however, are more familiar with the three needs as stand-along concepts rather than as part of the original theory itself.

The need for achievement arises from an individual’s desire to accomplish a goal or task as effectively as possible.10 Individuals who have a high need for achievement tend to set moderately difficult goals and to make moderately risky decisions. High-need achievers also want immediate, specific feedback on their performance. They want to know how well they did something as quickly after finishing it as possible. For this reason, high-need achievers frequently take jobs in sales, where they get almost immediate feedback from customers, and avoid jobs in areas such as research and development, where tangible progress is slower and feedback comes at longer intervals. Preoccupation with work is another characteristic of high-need achievers. They think about it on their way to the workplace, during lunch, and at home. They find it difficult to put their work aside, and they become frustrated when they must stop working on a partly completed project. Finally, high-need achievers tend to assume personal responsibility for getting things done. They often volunteer for extra duties and find it difficult to delegate part of a job to someone else. Accordingly, they derive a feeling of accomplishment when they have done more work than their peers without the assistance of others.

Many individuals also experience the need for affiliation—the need for human companionship.11 Researchers recognize several ways that people with a high need for affiliation differ from those with a lower need. Individuals with a high need tend to want reassurance and approval from others and usually are genuinely concerned about others’ feelings. They are likely to act and think as they believe others want them to, especially those with whom they strongly identify and desire friendship. As we might expect, people with a strong need for affiliation most often work in jobs with a lot of interpersonal contact, such as sales and teaching positions.

A third major individual need is the need for power—the desire to control one’s environment, including financial, material, informational, and human resources.12 People vary greatly along this dimension. Some individuals spend much time and energy seeking power; others avoid power if at all possible. People with a high need for power can be successful managers if three conditions are met. First, they must seek power for the betterment of the organization rather than for their own interests. Second, they must have a fairly low need for affiliation because fulfilling a personal need for power may well alienate others in the workplace. Third, they need plenty of self-control to curb their desire for power when it threatens to interfere with effective organizational or interpersonal relationships.14

Contemporary Motivation Theory

More complex and sophisticated models of employee behavior and motivation have been developed in recent years.15 Two of the more interesting and useful ones are expectancy theory and equity theory.

Expectancy Theory

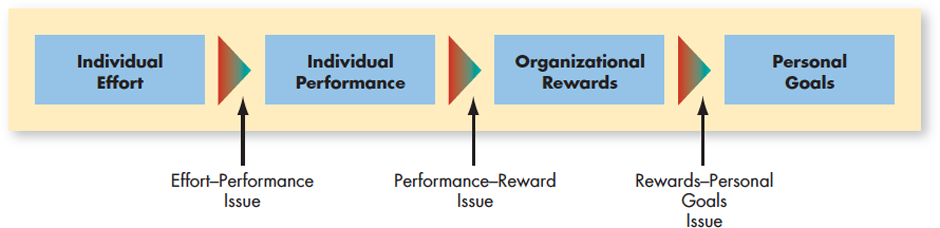

Expectancy theory suggests that people are motivated to work toward rewards that they want and that they believe they have a reasonable chance—or expectancy—of obtaining. A reward that seems out of reach is not likely to be motivating even if it is intrinsically positive. Figure 8.5 illustrates expectancy theory in terms of issues that are likely to be considered by an individual employee.

Figure 8.5

Expectancy Theory Model

Consider the case of an assistant department manager who learns that her firm needs to replace a retiring division manager three levels above her in the organization. Even though she might want the job, she does not apply because she doubts she will be selected. In this case, she considers the performance-reward issue: She believes that her performance will not get her the position because it would be such a large promotion. She also learns that the firm is looking for a production manager on the night shift. She thinks she could get this job but does not apply because she does not want to work nights (the rewards–personal goals issue). Finally, she learns of an opening one level higher—department manager—in her own division. She may well apply for this job because she both wants it and thinks that she has a good chance of getting it. In this case, her consideration of all the issues has led to an expectancy that she can reach a goal.

Expectancy theory helps explain why some people do not work as hard as they can when their salaries are based purely on seniority. Paying employees the same whether they work hard or just hard enough to get by removes the financial incentive for them to work harder. In other words, they ask themselves, “If I work harder, will I get a pay raise?” (the performance–reward issue) and conclude that the answer is “no.” Similarly, if hard work will result in one or more undesirable outcomes, such as a transfer to another location or a promotion to a job that requires unpleasant travel (the rewards–personal goals issue), employees will not be motivated to work hard.

Equity Theory

Equity theory focuses on social comparisons, people evaluating their treatment by the organization relative to the treatment of others. This approach suggests that people begin by thinking about their inputs (what they contribute to their jobs in terms of time, effort, education, experience) relative to their outputs (what they receive in return—salary, benefits, recognition, security). At this point, the comparison is similar to the psychological contract as discussed earlier. As viewed by equity theory, though, the result is a ratio of contribution to return. When they compare their own ratios with those of other employees, they ask whether their ratios are comparable to, greater than, or less than those of the people with whom they are comparing themselves. Depending on their assessments, they experience feelings of equity or inequity. Figure 8.6 illustrates the three possible results of such an assessment.

Figure 8.6

Equity Theory: Possible Assessments

For example, suppose a new college graduate gets a starting job at a large manufacturing firm. His starting salary is $65,000 a year, he gets an inexpensive company car, and he shares an assistant with another new employee. If he later learns that another new employee has received the same salary, car, and staff arrangement, he will feel equitably treated (result 1 in Figure 8.6). If the other newcomer, however, has received $75,000, a more expensive company car, and her own personal assistant, he may feel inequitably treated (result 2 in Figure 8.6).

Note, however, that for an individual to feel equitably treated, the two ratios do not have to be identical, only equitable. Assume, for instance, that our new employee has a bachelor’s degree and two years of work experience. Perhaps he learns subsequently that the other new employee has an advanced degree and 10 years of experience. After first feeling inequity, the new employee may conclude that the person with whom he compared himself is actually contributing more to the organization (more education and experience). That employee is perhaps equitably entitled, therefore, to receive more in return (result 3 in Figure 8.6).

When people feel they are being inequitably treated, they may do various constructive and some not so constructive things to restore fairness. For example, they may speak to their boss about the perceived inequity. Or (less constructively) they may demand a raise, reduce their efforts, work shorter hours, or just complain to their coworkers. They may also rationalize (“management succumbed to pressure to promote a woman/Asian American”), find different people with whom to compare themselves, or leave their jobs.