They all missed it. The ancient Greeks—mathematical luminaries such as Pythagoras, Theaetetus, Plato, Euclid, and Archimedes, who were infatuated with polyhedra—missed it. Johannes Kepler, the great astronomer, so in awe of the beauty of polyhedra that he based an early model of the solar system on them, missed it. In his investigation of polyhedra the mathematician and philosopher René Descartes was but a few logical steps away from discovering it, yet he too missed it. These mathematicians, and so many others, missed a relationship that is so simple that it can be explained to any schoolchild, yet is so fundamental that it is part of the fabric of modern mathematics.

The great Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707–1783)—whose surname is pronounced “oiler”—did not miss it. On November 14, 1750, in a letter to his friend, the number theorist Christian Goldbach (1690–1764), Euler wrote, “It astonishes me that these general properties of stereometry [solid geometry] have not, as far as I know, been noticed by anyone else.”2 In this letter Euler described his observation, and a year later he gave a proof. This observation is so basic and vital that it now bears the name Euler’s polyhedron formula.

A polyhedron is a three-dimensional object such as those found in figure I.1. It is composed of flat polygonal faces. Each pair of adjacent faces meets along a line segment, called an edge, and adjacent edges meet at a corner, or a vertex. Euler observed that the numbers of vertices, edges, and faces (V, E, and F) always satisfy a simple and elegant arithmetic relationship:

V − E + F = 2.

Figure I.1. A cube and a soccer ball (truncated icosahedron) both satisfy Euler’s formula.

The cube is probably the best-known polyhedron. A quick count shows that it has six faces: a square on the top, a square on the bottom, and four squares on the sides. The boundaries of these squares form the edges. Counting them, we find twelve total: four on the top, four on the bottom, and four vertical edges on the sides. The four top corners and the four bottom corners are the eight vertices of the cube. Thus for the cube, V = 8, E = 12, and F = 6, and of course

8 − 12 + 6 = 2,

as claimed. It is more tedious to count them, but the soccer-ball-shaped polyhedron shown in figure I.1 has 32 faces (12 pentagons and 20 hexagons), 90 edges, and 60 vertices. Again,

60 − 90 + 32 = 2.

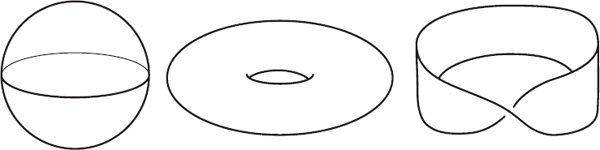

In addition to his work with polyhedra, Euler created the field of analysis situs, known today as topology. Geometry is the study of rigid objects. Geometers are interested in measuring quantities such as area, angle, volume, and length. Topology, which has inherited the popular moniker “rubber-sheet geometry,” is the study of malleable shapes. The objects a topologist studies need not be rigid or geometric. Topologists are interested in determining connectedness, detecting holes, and investigating twistedness. When a carnival clown bends a balloon into the shape of a dog, the balloon is still the same topological entity, but geometrically it is very different. But when a child bursts the balloon with a pencil, leaving a gaping hole in the rubber, it is no longer topologically the same. In figure I.2 we see three examples of topological surfaces—the sphere, the doughnut-shaped torus, and the twisted Möbius band.

Figure I.2. Topological surfaces: a sphere, a torus, and a Möbius band.

Figure I.3. Two partitions of the sphere.

Scholars in this young field of topology were fascinated by Euler’s formula, and they attempted to apply it to topological surfaces. The obvious question arose: where are the vertices, edges, and faces on a topological surface? The topologists disregarded the rigid rules set forth by the geometers and allowed the faces and edges to be curved. In figure I.3 we see a partition of a sphere into “rectangular” and “triangular” regions. The partition is formed by drawing 12 lines of longitude, meeting at the two poles, and 7 lines of latitude. This globe has 72 curved rectangular faces and 24 curved triangular ones (the triangular faces are located near the north and south poles), giving a total of 96 faces. There are 180 edges and 86 vertices. Thus, as with polyhedra, we find that

V − E + F = 86 − 180 + 96 = 2.

Likewise, the 2006 World Cup soccer ball, which consists of six foursided hourglass-shaped patches and eight misshapen hexagonal patches (see figure I.3), also satisfies Euler’s formula (it has V = 24, E = 36, and F = 14).

Figure I.4. A partition of the torus.

At this point we are tempted to conjecture that Euler’s formula applies to every topological surface. However, if we partition a torus into rectangular faces, as in figure I.4, we obtain a surprising result. This partition is formed by placing 2 circles around the central hole of the torus and 4 circles around its circular tube. The partition has 8 four-sided faces, 16 edges, and 8 vertices. Applying Euler’s formula we find

V − E + F = 8 − 16 + 8 = 0,

rather than the expected 2.

If we were to construct a different partition of the torus we would find that the alternating sum is still zero. This gives us a new Euler’s formula for the torus:

V − E + F = 0.

We can prove that every topological surface has its “own” Euler’s formula. No matter whether we partition the surface of a sphere into 6 faces or 1,006 faces, when we apply Euler’s formula we will always get 2. Likewise, if we apply Euler’s formula to any partition of the torus, we will get 0. This special number can be used to distinguish surfaces just as the number of wheels can be used to distinguish highway vehicles. Every car has four wheels, every tractor trailer has eighteen wheels, and every motorcycle has two wheels. If a vehicle does not have four wheels, then it is not a car; if it does not have two wheels, then it is not a motorcycle. In the same way, if V − E + F is not 0, then topologically the surface is not a torus.

The sum V − E + F is a quantity intrinsically associated with the shape. In the lingo of topologists, we say that it is an invariant of the surface. Because of this powerful property of invariance, we call the number V − E + F the Euler number of the surface. The Euler number of a sphere is 2 and the Euler number of a torus is 0.

Figure I.5. Are these the same knot?

At this point, the fact that every surface has its own Euler number may seem nothing more than a mathematical curiosity, an “isn’t that cool” kind of fact to contemplate while holding a soccer ball or looking at a geodesic dome. This is most certainly not the case. As we will see, the Euler number is an indispensable tool in the study of polyhedra, not to mention topology, geometry, graph theory, and dynamical systems, and it has some very elegant and unexpected applications.

A mathematical knot is like an intertwined loop of string as shown in figure I.5. Two knots are the same if one knot can be deformed into the other without cutting and re-gluing the string. Just as we can use the Euler number to help distinguish two surfaces, with a little ingenuity we can also use it to distinguish knots. We can use the Euler number to prove that the two knots in figure I.5 are not the same.

In figure I.6 we see a snapshot of wind patterns on the surface of the earth. In this example there is a point off the coast of Chile where the wind is not blowing. It is located in the calm spot within the eye of the storm that is spinning clockwise. We can prove that there is always at least one point on the surface of the earth where there is no wind. This follows not from an understanding of meteorology, but from an understanding of topology. The existence of this point of calm comes from a theorem that mathematicians refer to as the hairy ball theorem. If we think of the wind directions as strands of hair on the surface of the earth, then there must be some point where the hair forms a cowlick. Colloquially, we say that “you can’t comb the hair on a coconut.” In chapter 19 we will see how the Euler number enables us to establish this bold assertion.

Figure I.6. Is there always a windless location on earth?

Figure I.7. Is it possible to determine the area of the shaded polygon by counting dots?

In figure I.7 we see a polygon sitting in an array of dots spaced one unit apart. The vertices of the polygon are located at the dots. Surprisingly, we can compute the precise area of the polygon simply by counting dots. In chapter 13 we will use the Euler number to derive the following elegant formula that gives the area of the polygon in terms of the number of dots that lie along the boundary of the polygon (B) and the number of dots in the interior of the polygon (I):

Area = I + B/2 − 1.

From this formula we conclude that our polygon’s area is 5 + 10/2 − 1 = 9.

There is an old and interesting problem that asks how many colors are required to color a map in such a way that every pair of regions with a common border are not the same color. Take a blank map of the United States and color it with as few crayons as possible. You will quickly discover that most of the country can be colored using only three crayons, but that a fourth is needed to complete the map. For instance, since an odd number of states surround Nevada, you will need three crayons to color them—then you will need that fourth crayon for Nevada itself (figure I.8). If we are clever, then we can finish the coloring without using a fifth—four colors are sufficient for the entire map of the United States. It was long conjectured that every map can be colored with four or fewer colors. This infamous and very slippery conjecture became known as the four color problem. In chapter 14 we will recount its fascinating history, one that ended with a controversial proof in 1976 in which the Euler number played a key role.

Figure I.8. Can we color the map of the United States using only four colors?

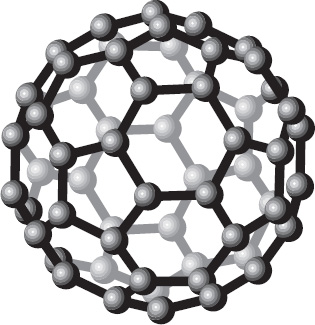

Figure I.9. The C60 buckminsterfullerene molecule.

Graphite and diamond are two materials whose chemical makeup consists entirely of carbon atoms. In 1985 three scientists—Robert Curl Jr., Richard Smalley, and Harold Kroto—shocked the scientific community by discovering a new class of all-carbon molecules. They called these molecules fullerenes, after the architect Buckminster Fuller, inventor of the geodesic dome (figure I.9). They chose this name because fullerenes are large polyhedral molecules that resemble such structures. For the discovery of fullerenes the three men were awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in chemistry. In a fullerene every carbon atom bonds with exactly three of its neighbors, and rings of carbon atoms form pentagons and hexagons. Initially Curl, Smalley, and Kroto found fullerenes possessing 60 and 70 carbon atoms, but other fullerenes were discovered later. The most plentiful fullerene is the soccer-ball-shaped molecule C60 that they called the buckminsterfullerene. Remarkably, knowing no chemistry and only Euler’s formula, we are able to conclude that there are certain configurations of carbon atoms that are impossible in a fullerene. For instance, every fullerene, regardless of the size, must have exactly 12 pentagonal carbon rings even though the number of hexagonal rings can vary.

Figure I.10. The five regular solids.

For thousands of years people have been drawn to the beautiful and alluring regular solids—polyhedra whose faces are identical regular polygons (figure I.10). The Greeks discovered these objects, Plato incorporated them into his atomic theory, and Kepler based an early model of the solar system on them. Part of the mystery surrounding these five polyhedra is that they are so few in number—no polyhedron other than these five satisfies the strict requirements of regularity. One of the most elegant applications of Euler’s formula is a very short proof that guarantees that only five regular solids exist.

Despite the importance and beauty of Euler’s formula, it is virtually unknown to the general public. It is not found in the standard curriculum taught in the schools. Some high school students may know Euler’s formula, but most students of mathematics do not encounter this relation until college.

Mathematical fame is a curious thing. Some theorems are well known because they are drilled into the heads of young students: the Pythagorean theorem, the quadratic formula, the fundamental theorem of calculus. Other results are thrust into the spotlight because they resolve a famous unsolved problem. Fermat’s last theorem remained unproved for over three hundred years until Andrew Wiles surprised the world with his proof in 1993. The four color problem was posed in 1853 and was only proved by Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken in 1976. The famous Poincaré conjecture was posed in 1904 and was one of the Clay Mathematics Institute Millennium Problems—a collection of seven problems deemed so important that the mathematician who solves one receives $1 million. The money is likely to be awarded to Grisha Perelman, who gave a proof of the Poincaré conjecture in 2002. Other mathematical facts are well known because of their cross-disciplinary appeal (the Fibonacci sequence in nature) or their historical significance (the infinitude of primes, the irrationality of π).

Euler’s formula should be as well known as these great theorems. It has a colorful history, and many of the world’s greatest mathematicians contributed to the theory. It is a deep theorem, and one’s appreciation for this depth grows with one’s mathematical sophistication.

This is the story of Euler’s beautiful theorem. We will trace its history and show how it formed a bridge from the polyhedra of the Greeks to the modern field of topology. We will present many surprising guises of Euler’s formula in geometry, topology, and dynamical systems. We will also give examples of theorems whose proofs rely on Euler’s formula. We will see why this long-unnoticed formula became one of the most beloved theorems in mathematics.