CHAPTER FOUR

Sources of Bank Funds

CHAPTER STRUCTURE

Section II Bank Liabilities—Deposits

Section III Pricing Deposit Services

Section IV Bank Liabilities—Non-Deposit Sources

Section V Bank Deposits in India—Some Important Legal Aspects

Section VI Design of Deposit Schemes—Some Illustrations

Annexures I, II, III, lV, V (Case study)

KEY TAKEAWAyS FROM THE CHAPTER

- Understand the nature of bank liabilities.

- Learn about the nature of bank deposits.

- Understand deposit pricing strategies.

- Learn about non-deposit funding sources of banks.

- Understand the legal aspects of deposits in India.

SECTION I

BASIC CONCEPTS

We have seen in earlier chapters that banks, in their role as financial intermediaries, provide the vital link between savers and users of funds in the economy.

The ability of a bank to attract money from customers and businesses is a vital signal of the bank’s acceptance in the market. In today’s competitive environment, where returns from the capital markets or mutual funds are more attractive, banks find liability management a challenge. Banks have to constantly innovate—whether it is in product development or customer service.

Liability management plays a critical role in the risk—return profile of banks. In the present deregulated environment, banks have to balance profitability and risks while deciding on their liability mix. For example, if banks price their liabilities higher to lure more depositors, their interest expenses would rise. Further, the deposit rates are also subject to change, which lead to interest rate risk. Deposits could be withdrawn at any time, leading to liquidity risk for the bank. The bank would have created assets out of these deposits and in the event of sudden withdrawal of the deposits, the bank would also be subject to a refinancing risk.

We have seen in an earlier chapter that ‘deposits’ are the primary sources of funds for banks. The other sources of funds for banks are ‘equity and reserves’ and ‘borrowings’.

The sources of funds as described above form the basis for creation of assets by the bank and are hence responsible for the bank’s profit and growth. Therefore, it would be prudent for the bank to base its funds requirement and mobilization on some relevant parameters, such as:

- Maturity: Deposit holders in a bank are a diverse lot. They are from divergent backgrounds, from small depositors to large corporations, financial institutions and governments. They have different needs and planning horizons and would require their savings back at different points in time. Each instrument would have to be priced differently, in terms of the prevailing regulations and the bank’s strategy. The maturity of each debt instrument is vital for the bank, since it has to plan for repayment at the end of the period with no risk of default. Further, it has to forecast the interest rates that could prevail at the end of the period.

- Cost of funds: Investors look for reasonable return on their investments when they put their savings into a bank. However, the bank should consider the yield from investing these funds in assets such as loans or investments, so that its target profit can be achieved.

- Tax implications: Depositors would prefer to look at post-tax cash flows from their investments. Even if the bank prefers to borrow from a particular source, the availability of funds would be determined by tax rules in force.

- Regulatory framework: Regulations in force would very often determine the attractiveness of one source of funds over the other.

- Market conditions: The prevailing sentiment in the market and the investors’ attitude towards risk would predominantly determine the amount of funds that would flow into banks.

It is, therefore, evident that a host of dynamic factors would determine the availability and cost of bank funds at any point of time. Preferences and investment objectives of depositors are changing over time and hence, banks may not be able to source the type of funds that they desire in the market.

In the following sections, we will look at the features of bank deposits and other non-deposit borrowings.

SECTION II

BANK LIABILITIES—DEPOSITS

Bank deposits are differentiated by the type of deposit customer, the tenure of the deposit and its cost to the bank. On the basis of these parameters, deposits can be broadly classified as follows:

- Transaction accounts or payment deposits: These deposits, repayable by the bank on demand from the depositor, represent one of the primary services offered by banks. They can be bifurcated into non-interest bearing and interest bearing demand deposits. Such deposits facilitate transfer of funds by the deposit holder to third parties, primarily through cheques1 and other forms of funds transfer. Cheques are attractive because they provide easy and formal verification and are readily accepted as a recognized mode of payment.

Non-interest bearing demand deposits are typically held by individuals, businesses or the government. Explicit interest payments on these deposits are prohibited in most countries. However, there are no regulations restraining banks from prescribing minimum balances or transaction charges. Corporate customers prefer these accounts for ease of operation. These are generally large deposits and can be quite volatile sources of funds for the bank.

Interest bearing demand deposits are preferred by individuals or certain types of organizations. Similar to the non-interest bearing accounts, these deposits are also used for the purpose of transactions by the deposit holders and a major portion of these deposits is likely to be volatile. They are called ‘savings’ accounts in some countries (as in India), since the depositors park their earnings in these accounts to be used for routine and other payments. These deposits carry a low rate of interest (in many countries, this rate of interest is prescribed by the regulator).

- Term deposits: These are a form of ‘debt investment’ for a customer, who is willing to lend money to the bank for a specified period of time. In return, the customer receives a stream of cash flows in the form of interest. These deposits typically pay higher interest. A popular variant of large term deposits is the certificate of deposit (CD)

Box 4.1 describes some of the prominent types of deposit accounts in select countries.

BOX 4.1 FEATURES OF DEPOSIT ACCOUNTS IN SELECT COUNTRIES

The USA

In the early 1970s, in New England, hybrid checking—savings accounts called negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts were introduced. These were meant to be interest bearing savings deposits that required the customer to give notice to the bank before withdrawing funds. However, the notice requirement is not insisted upon and the NOW is being used like any other checking account.

In the US, most banks predominantly offer three different transaction accounts—demand deposit accounts (DDAs), interest bearing NOW accounts or automatic transfer from savings (ATS) accounts and money market deposit accounts (MMDAs). Investors seeking relatively low risk investment that can easily be converted into cash go in for CDs. Banks differentiate between these deposits on parameters, such as the minimum balance required, the number of transfers/cheques permitted and the interest rate paid. All deposits are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) up to USD 100,000 per account.

DDAs are non-interest bearing checking accounts, predominantly held by commercial units, though individuals and the government can also hold such accounts.

A NOW account is an interest bearing demand deposit. An ATS account is similar to a NOW account, with the difference that in the ATS account a customer has both the DDA and savings accounts, with the balance in the DDA account being brought down to ‘nil’ at the end of each day through transfer of funds from the savings account. NOW accounts are priced competitively and can be held only by individuals and non-profit organizations.

MMDAs were primarily introduced to enable banks compete with money market mutual funds offered by large brokerage houses. These are basically ‘term’ deposits and not transaction accounts. Though the average size of an MMDA account could be much larger than a transaction account, cheque usage and transactions are limited.

A CD is a special type of deposit account with a bank that typically offers a higher rate of interest than regular savings account. In a CD, a fixed sum of money, usually large, is invested for a fixed period of time and in exchange, the bank pays interest typically at regular intervals. Though CDs were designed to pay a fixed interest rate until maturity, they now pay variable rates as well. Further, CDs can be issued with special features, such as ‘call’ provisions. Zero coupon CDs ensure long-term funds for banks without periodical interest pay outs. Some banks also issue CDs with yields linked to a stock market index such as S&P 500 to lure investors who could otherwise take their money out of banks.

The UK

es of deposit accounts are:

- Current account, which provides a cheque-book but usually pays no interest.

These accounts are primarily used for paying bills.

- Deposit account, which pays interest and is used primarily for short-term saving.

- Investment or savings account, which pays a higher rate of interest and is used primarily for long-term saving. Notice of withdrawal must be given in writing.

Australia

‘Deposits’ include transaction and non-transaction deposit accounts and CDs.

Canada

The predominant types of deposit accounts are savings and cheque accounts, term deposits and guaranteed investment certificates (GICs). GICs are term investments that require depositors to lock in their investment for a set length of time. GICs generally pay higher rates of interest than term deposits, but are often not redeemable before maturity. The Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC) insures eligible deposits up to a limit of USD 100,000 per depositor in each member institution.

Protecting the Depositor—Deposit Insurance

Deposit insurance is a measure taken by banks in most countries to protect small depositors’ savings, either fully or in part, against any possible risk of a bank not being able to return their savings to these depositors. Deposit insurance institutions are mostly government-established and managed and may or may not form part of a country’s central bank.

The US was the first country to initiate an official deposit insurance scheme, triggered by a banking crisis during the Great Depression in 1934. [As of end June 2013, 112 countries had some form of explicit deposit insurance. Another 41 countries were actively considering implementation of explicit deposit insurance.]

Many of the deposit insurance agencies are members of the International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI). This organization was established in 2002 to promote deposit insurance, help countries without deposit insurance schemes to establish their own institutions for this purpose and promote knowledge and experience exchange between deposit insurers in various countries. Box 4.2 provides details on IADI and principles of deposit insurance.

BOX 4.2 THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF DEPOSIT INSURERS (IADI)

Introduction to IADI

IADI was founded on 6 May 2002. It is a non-profit organization, constituted under Swiss law.

The genesis of IADI was the Working Group on Deposit Insurance established by the Financial Stability Forum (FSF)2 in 2000.

The IADI has four categories of participation—Members, Associates, Observers, and Partners. In April 2017, IADI had 83 members. Members are entities/countries that, under law or agreement, have a deposit insurance system and have been approved for membership by IADI.

Associates are entities that do not fulfil all the criteria to be a Member, but are considering the establishment of a deposit insurance system, or are part of a financial safety net and have a direct interest in the effectiveness of a deposit insurance system.

Observers are not-for-profit entities such as international organizations which do not fulfil the criteria to be an Associate but have a direct interest in the effectiveness of deposit insurance systems.

Partners are not-for-profit entities such as international institutions that enter into a cooperative arrangement with the Association in the pursuit and furtherance of the Objects of the Association.

The IADI-BCBS Core Principles for Effective Deposit Insurance Systems (2009 and revised in 2014)

The financial crisis of 2008 prompted the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS)3 and the International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI) to collaborate for developing an internationally applicable set of ‘Core Principles’. The IADI ‘Core principles for effective deposit insurance systems’ served as the basis for the new set of core principles.

The document sets the following preconditions for an effective deposit insurance system:

- An ongoing assessment of the economy and banking system;

- Sound governance of agencies comprising the financial system safety net;

- Strong prudential regulation and supervision; and

- A well developed legal framework and accounting and disclosure regime.

The experience with the Core principles of 2009 led to revisions in 2014. The revised set of principles include the following enhancements:

- improving the clarity and consistency of terminology;

- reducing overlap and duplication among a number of Core Principles;

- strengthening the Core Principles in certain areas (e.g. governance, depositor reimbursements, coverage, funding) and improving safeguards for the use of deposit insurance funds;

- incorporating IADI enhanced guidance on reimbursements, public awareness, coverage, moral hazard, and funding;

- addressing moral hazard concerns within all relevant Core Principles instead of restricting moral hazard guidance to a single Core Principle;

- updating the Core Principles related to intervention and failure resolution, in order to better reflect the greater role being played by many deposit insurers in resolution regimes, and to ensure the consistency of the Core Principles with the FSB Key Attributes;

- adding more guidance on deposit insurers’ role in crisis preparedness and management;

- incorporating considerations related to the operation of Islamic deposit insurance systems;

- updating and enhancing Core Principles related to cross-border deposit insurance issues;

- adding guidance on the operation of multiple deposit insurance systems in the same national jurisdiction; and

- upgrading some additional criteria to essential criteria while adding new assessment criteria where warranted.

The 16 revised Core Principles are broadly intended to deal with the aspects listed below. In revising the core principles, the key considerations have been stated to be (a) moral hazard, (b) operating environment (that includes macro economic environment, financial system, prudential regulation, supervision and regulation, the legal and judicial framework and the accounting and disclosure system), and (c) some special issues (such as Islamic deposit insurance systems, multiple deposit insurance systems, financial inclusion and depositor preference).

Principle 1 sets out ‘Public Policy objectives’ that should primarily focus on financial system stability and depositor protection.

Principle 2 elaborates on the consistency between public policy objectives and the ‘mandate’—powers and responsibilities given to the deposit insurer.

Principle 3 emphasizes ‘governance’ aspects such as operational independence, transparency, accountability and insulation from undue political and industry influences, in order to function effectively.

Principle 4 describes the nature of ‘relationships with other safety net participants’. Close coordination and sharing of information should be part of the framework.

Principle 5 deals with ‘cross border issues’ where deposit insurers in different jurisdictions and foreign participants are involved.

Principle 6 sets out the deposit insurer’s role in contingency planning and crisis management.

Principle 7 suggests ‘compulsory membership’ for all financial institutions accepting deposits from small depositors and those most in need of such protection.

Principle 8 deals with ‘coverage’ issues such as legal definition of insurable deposit, or quick determination of level of coverage, which could be limited but should cover the large majority of depositors to meet public policy objectives.

Principle 9 deals with the ‘funding’ aspects of the system to ensure prompt reimbursement of depositors’ claims. The primary responsibility for paying the cost of deposit insurance should be borne by banks. Where deposit insurance used risk adjusted differential premium systems, the criteria and administrative aspects should be made transparent.

Principle 10 deals with ongoing information to the public about the limitations and benefits of the deposit insurance system, in order to create ‘public awareness’.

Principle 11 deals with ‘legal protection’ to the deposit insurer for decisions and actions taken in ‘good faith’.

Principle 12 ‘dealing with parties at fault in a bank failure’, states that the deposit insurer should be provided with the power to seek legal redress against those parties at fault in a bank failure.

Principle 13 emphasizes on ‘early detection and timely intervention and resolution’ of troubled banks.

Principle 14 calls for “failure resolution regime” to enable deposit insurer to provide for depositor protection and contribute to financial stability.

Principle 15 emphasizes on ‘reimbursing depositors’ promptly in conditions under which the reimbursement is to be made. Depositors should be informed of their legal right to reimbursement, the coverage limit, the time frame over which payments will be made, and so on.

Principle 16 deals with ‘recoveries’ by the deposit insurer from the failed bank’s assets.

Deposit insurance is being increasingly used by governments as a tool to ensure the stability of the banking system of their countries and protect bank depositors from incurring large losses due to bank failures. Actually, almost all countries have some kind of financial safety nets in place to protect depositors. These could take the form of bank regulation and supervision, lender of last resort facilities from the central bank, bank insolvency resolution procedures or explicit and implicit deposit insurance. Although deposit insurance is used as a popular tool, its desirability is debated by many economists who point to the moral hazard problems and the accompanying excessive risk being taken by banks.

However, between creation of possible ‘moral hazard’ by deposit insurance systems and financial stability, the choice is clear. Financial stability has to be preserved at any cost, this fact was highlighted by the recent financial crisis.

The Financial Stability Board’s ‘Thematic Review of Deposit Insurance Systems’ (DIS) published in February 2012, throws up interesting facts and comparisons, post the financial crisis of 2007–08. Some of these are given below:

- Explicit deposit insurance has become the preferred choice of most countries. Australia, Palestine, and Mongalia are some of the latest countries to establish an explicit deposit insurance system. China and South Africa have confirmed their plans to introduce deposit insurance. However, Saudi Arabia is not convinced about introducing a deposit insurance system in the country.

- Those countries with explicit deposit insurance systems (including India) are broadly in conformity with the ‘Core Principles for effective deposit insurance systems’ issued by BCBS and IADI (see Box 4.2).

- Some of the areas of divergence from the core principles are observed in the following countries:

- In some countries like Switzerland, certain non-bank institutions taking deposits from the public and participating in the national payments system are not covered by the domestic DIS.

- In some jurisdictions (e.g., Germany, Japan, United States), the coverage limits—both in terms of the proportion of depositors covered and the value of deposits covered are relatively high. The report notes that although a high coverage level reduces the incentives for depositors to run, adequate controls are needed to ensure a proper balance between financial stability and market discipline.

- In the case of Switzerland, the existence of a system-wide limit of CHF 6 billion on the total amount of contributions by participating members in the DIS could create the perception in times of stress that some insured deposits would not be reimbursed in the event of a (large) bank failure.

- The payout systems vary significantly from country to country, such as, the institution that triggers a claim for payment or the speed of depositor reimbursement. In Germany, the institutional protection schemes do not have any arrangements to reimburse depositors because they protect their member institutions against insolvency and liquidation. In Switzerland, depositor reimbursement is the responsibility of the failed bank’s liquidator as opposed to the deposit insurance agency (DIA).

- The starting date used to set the payout timeframes also differs. Adequate payout arrangements—such as early information access via a single customer view—are the practice in the United States. Some countries such as the Netherlands, Singapore and the United Kingdom have shifted from a net to a gross payout basis, i.e., the insured deposits will not be offset against the depositor’s liabilities owed to the failed bank.

- The mandates of DISs in FSB member jurisdictions are generally well defined and formalized, and may be broadly classified into four categories:

- Narrow mandate systems that are only responsible for the reimbursement of insured deposits (‘paybox’ mandate)—such as in Australia, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Netherlands, Singapore, Switzerland;

- A ‘paybox plus’ mandate, where the deposit insurer has additional responsibilities such as resolution functions—such as in Argentina, Brazil, United Kingdom;

- A ‘loss minimizer’ mandate, where the insurer actively engages in the selection from a full suite of appropriate least-cost resolution strategies—such as in Canada, France, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Spain, Turkey; and

- A ‘risk minimizer’ mandate, where the insurer has comprehensive risk minimization functions that include a full suite of resolution powers as well as prudential oversight responsibilities—such as in Korea, United States.

The mandates of certain DISs have been expanded or clarified following the financial crisis:

- The composition of the governing body varies across countries and generally reflects a variety of safety net participants and relevant stakeholders. However, some DIAs are dominated by representatives from the government (e.g., Russia), the banking industry (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Italy, Switzerland), or the supervisor.

- The provision of cross-border deposit insurance is concentrated primarily in those countries within the European Economic Area. However, even in countries not extending protection to overseas deposits, local depositors in foreign-owned bank branches may still be eligible for protection by the foreign (home authority) DIS.

- Some countries run multiple DISs, e.g., Brazil, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, United States.

- While the global trend is towards establishing DIS with ex-ante funds, some countries such as Australia, Italy, Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are presently supported solely by an ex-post funding system.

What happens when an insured bank fails? The insuring agency typically has the following options in the event of bank failure4: It can invite bids from healthy banks for the sale of the failed bank, in which case the insured depositors’ accounts will be shifted to the new bank rather than being paid off by the agency; it can give financial assistance to the bank interested in acquiring the failed bank, so that depositors of the failed bank can start having accounts with the acquiring bank; it can transfer all insured deposits to a healthy bank; it can take charge and manage the operations of the failed bank till it finds a suitable buyer or it can pay off the depositors up to the maximum allowed.

Deposit Insurance in India

The Deposit Insurance Corporation (DIC), established under the Deposit Insurance Act, 1961, came into being in 1962, following two bank failures (Laxmi Bank and the Palai Central Bank). India was the second country in the world to introduce the Scheme—the first being the United States in 1934. Initially, the system covered exclusively the commercial banks. In 1968, cooperative banks with a minimum size operating in states having pertinent legislation was included in the system. In 1975, coverage was extended to rural banks as well. In 1978, the deposit insurance and credit guarantee functions were integrated to form the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC). But over time the credit guarantee schemes were delinked. The coverage limits have been changed in time as follows: initially ₹1,500; ₹5,000 in 1968; ₹10,000 in 1970; ₹20,000 in 1976; ₹30,000 in 1980 and ₹ 1,00,000 since 1 May 1993. The system is administered officially. Certificates of deposit, government, inter-bank and illegal deposits are not covered. More information on the operational aspects of the scheme is available at www.dicgc.org.

The 2015-16 annual reports of RBI and Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation of India (DICGC) present the following information:

- The number of registered insured banks at the end of March, 2016 stood at 2127, comprising of 93 commercial banks, 56 regional rural banks, 4 local area banks, and 1974 cooperative banks. DICGC insures depositors of all commercial banks, including RRBs, Local Area Banks, cooperative banks, small finance banks and payment banks.

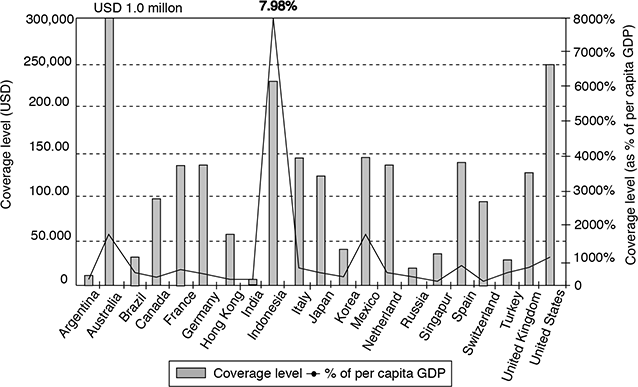

FIGURE 4.1 COMPARISON OF ABSOLUTE LEVEL AND PER CENT OF PER CAPITA GDP–INDIA WITH SELECT COUNTRIES

- b. The 1553 million fully protected accounts form 92.3 per cent of the total 1682 million accounts in the banking system. The international benchmark in this respect is 80 per cent.

- c. Insured deposits amounted to ₹28264 billion. This constituted 30 per cent of assessable deposits against the international benchmark of 20–40 per cent.

- d. At the March 2016 level, the insurance cover is 1.1 times India’s per capita income. Figure 4.1 compares India’s deposit insurance cover with that of other countries at the end of 2010.

- e. The deposit insurance fund (DIF) is built through transfer of the Deposit insurance Corporation’s surplus—excess of income (primarily premium received from insured banks, interest income from investments and cash recovery out of assets of failed banks) over expenses, each year. This fund is used for settlement of claims of depositors of banks going into liquidation/reconstruction/amalgamation, etc. At the end of March 2016, the corpus of the DIF was Rs 602.5 billion.

SECTION III

PRICING DEPOSIT SERVICES

The Need to Price with Precision

The pricing of deposits and related services assumes great importance in the present deregulated and highly competitive environment, where deposit rate ceilings do not exist. However, banks have to monitor the cost of their funding sources carefully for the following reasons:

- Changes in cost of funds would require changes in asset yields to maintain spreads

- Changes in cost of funds could alter the liability mix of banks and expose the bank to liquidity constraints

- Changes in cost of funds could render the bank less competitive in the market

It is, therefore, imperative that banks understand how to measure the cost of their funding sources and accordingly price their assets in order to ensure a desired level of profitability. This is done through a pricing policy.

The pricing policy of a bank is typically a written document that lays down guidelines for evaluating deposit sources and pricing them effectively. Generally, the following key aspects would be considered before arriving at a pricing decision:

- Servicing costs versus minimum balance requirements

- Deposit volumes and their costs in relation to profits

- Lending and investment avenues and compensating balances

- Relationship with customers

- Promotional pricing, if new products are being considered

- Product differentiation in a competitive market

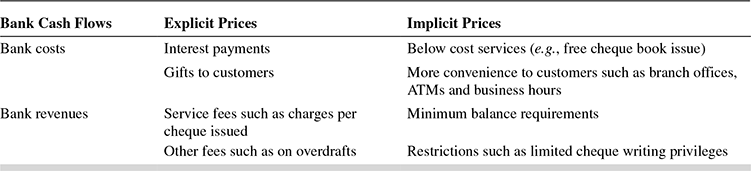

Therefore, measuring the cost of funds should take into account both explicit and implicit costs associated with sourcing the deposits.

The explicit costs would be interest payments on the deposits and giveaways and gifts to promote the deposit product. However, even in non-interest bearing transaction deposits, where no explicit interest is paid out, there are implicit costs, such as a provision of services like free cheque books to the customer and added convenience for customer transactions, such as provision and maintenance of ATMs and branch offices. To compensate for these transaction costs, some banks levy fees depending on the frequency of cheque usage or ATM usage or prescribe a minimum balance maintenance in customers’ accounts. Table 4.1 depicts some typical explicit and implicit prices and their impact on bank revenues and costs.

TABLE 4.1 EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT PRICES AND THEIR IMPACT ON BANK REVENUES AND COSTS

Developing a sound deposit pricing methodology is gaining greater importance since banks have to look more to non-core sources for funding their assets. One reason for this is the intense market competition and the other is the changing asset profile of banks that requires sources with different maturities and risk profiles.

The traditional approach to deposit pricing was a ‘supply–side’ approach. Deposit rates reflected what competition was paying for similar products and what the bank could ‘afford’. The most serious drawback of this approach was that it ignored both customer needs and the underlying demand elasticity of deposits. This resulted in specialized competitors like investment banks targeting the most desirable customer segments through product offerings that combine rate and convenience—products that banks could barely match.

Most banks have now, therefore, shifted to the ‘demand side’ approach. This view considers the degree to which customer demand varies with the deposit rate offered. This demand elasticity is analyzed and quantified by major products, geographies or customer segments.

For example, deposit rates could be computed separately for large time deposits, non-transaction (excluding large time) deposits and transaction deposits. This allows the evaluation of deposit pricing strategy for these three different classes of deposit investors.

Recent research5 indicates that in reality, deposit customers are fairly tolerant of price changes. The cited report also notes that ‘if they (banks) had more flexibility to price retail products without sparking widespread customer defections, they could boost their bottom-line retail earnings by as much as 5–7 per cent’. The research also found that ‘checking account’ customers rated convenience, service quality and relationship with the bank over price increases. More than one-third of these customers were unable to even recall when the last price change occurred and in the end, just 2 per cent of all customers moved their accounts to another bank.

Such analysis could help banks avoid raising rates (and lowering profitability) to attract deposits in customer segments which are known to be price inelastic. Or the information could help in fine tuning the deposit prices in customer segments where better rates would be a deciding factor for a customer to keep deposits in or move them out of a bank. Better informed tradeoffs would enable better use of resources to improve service or convenience than to raise deposit rates.

There are also other drivers to deposit growth. Exogenous factors such as macroeconomic factors or movements in the financial markets may impact the flow of deposits in and out of the banking system. Banks can do little in influencing these factors. However, they need to understand the nature of these flows. For example, when the interest rates are ruling high, customers would gravitate to high interest paying deposits (transitioning from checking accounts which would pay lower) or to the markets. When interest rates move southward, investors may prefer to invest in short-term instruments, such as savings deposits or money market accounts. Such trends can be forecasted reasonably accurately and blended into the pricing strategy of the bank.

The second factor driving deposit growth is endogenous. Banks can attract more deposits by appropriate promotion and pricing strategies and by reflecting a robust value proposition for the long-term. Best practice banks are increasingly analyzing customer price elasticities by product, to enable specific quantification of the potential volume and revenue impact associated with a given price position.6 The cited article7 adds, ‘Such an analysis reveals an “area of indifference” around the average market price for each product. Within this zone, consumers are apparently indifferent to small pricing changes. Outside this zone, demand rises dramatically in response to rate increases and then flattens out again. Above a certain point, higher rates do not have a commensurate impact on balances’.

An important point to be noted here is that proper deposit pricing will have a positive effect on the growth of net interest income and net interest margin. Some common practices adopted by banks for improving profitability while pricing deposits are:

- Setting deposit prices in keeping with the deposit origination cost. For example, the origination cost of two deposits of say, ₹100 crores and ₹10 crores may be almost the same, but the larger deposit can provide an opportunity for the bank to create an asset that is 10 times larger. Therefore, the pricing could be based on the deposit amount.

- Paying higher rates for longer term deposits. This again depends on the nature of assets the bank wants to create.

- Banks prefer adding interest to principal or paying interest by automatic transfer to another internal account, to issue periodic interest payments to the customer. The latter practice is less expensive.

Some Commonly Used Approaches to Deposit Pricing

1. Cost Plus Margin Deposit Pricing

This type of pricing encourages banks to determine the deposit rate as one that would be adequate to cover all costs of offering the service, plus a small profit margin. Banks incur costs such as personnel and management time, material and automation in offering each deposit service. In a deregulated environment, the pressure is on banks’ profitability in terms of higher cost of funds, thinning net interest margins and higher cost of customer solicitation and retention. If deposit pricing is not related to banks’ costs in extending deposit services, the bank could end up exacerbating the pressure on profitability.

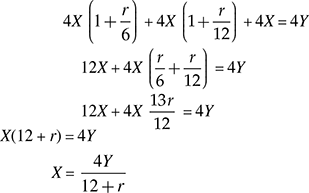

Thus, the price of deposit services would typically conform to the following ‘cost plus deposit pricing’ formula:

Unit price charged to the customer per deposit service = Operating expense per unit of deposit service + Estimated overhead expense allocated to deposit function + Planned profit from each deposit unit

Relating deposit prices to costs as above has encouraged banks to match prices and costs more closely and allocate prices to many services that were earlier rendered free. Thus, in most countries today, banks levy fees for excessive withdrawals from transaction deposits, customer balance enquiries, cheques returned without being paid, stop payment orders, ATM operations and so on and also prescribe required minimum deposit balances.

2. Market Penetration Deposit Pricing

This pricing strategy is typically aimed at high growth markets in which the bank is determined to garner a large market share. Therefore, banks are tempted to offer either high interest rates, well above the market level or charge customer fees well below the market standards. Bank managers expect that the large sources of funds and the associated loan business and investment opportunities would offset thinner spreads. Because it is usually costly for a customer to move certain kinds of deposits such as payment accounts, the lower fees on certain deposits initially attracted through penetration pricing which may eventually be raised to a cost-recovery or profit-making level.

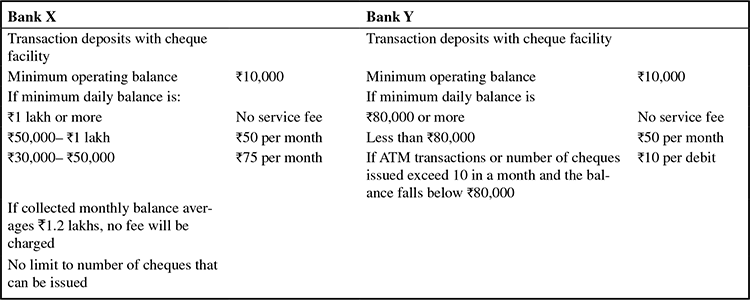

3. Conditional Pricing

Conditional pricing can be used by banks as a tool to attract the types of depositors they want as customers. Under this pricing technique, the bank will post a schedule of interest rates or fees for deposits based on size of deposits or account activity. Typically, larger volume deposits carry higher interest rates or lower fees. This strategy is mostly designed to encourage customers to hold high average deposit balances for a given period of time, which, in turn, could be invested in earning assets.

An added advantage of this pricing strategy is that the customer chooses a deposit plan suitable for the customer and not for the bank. This selection process serves as a signal to the markets and the bank itself regarding the behaviour and cost of its deposits.

The following hypothetical example would serve to illustrate how two banks use conditional pricing to attract a certain class of deposit customers.

In the above example, Bank X seems to prefer relatively low activity but high balance transaction and savings accounts, while Bank Y is not averse to smaller accounts. This is evident from the way the service fees are structured. Generally, larger volume deposits carry higher interest returns to the depositor or are assessed lower service charges, encouraging customers to hold high average deposit balances which give the bank more funds to invest in earning assets.

In such cases, banks’ deposit pricing policy is typically sensitive to the customer segments that each bank plans to serve and the costs incurred by the banks in serving different customer segments.

4. Upscale Target Pricing

Upscale target pricing is the use of carefully but aggressively designed deposit advertising programs and deposit pricing schemes to appeal to customers with higher levels of income or net worth, such as business owners and managers, doctors, lawyers and other high income households. The customers being targeted are price sensitive and therefore could respond quickly to the price differentials.

5. Relationship Pricing

Relationship pricing typically ensures that the bank’s best customers get the best pricing. It involves basing fees charged to a customer not only on the number of services that the customer purchases from the bank, but also on the intensity of use of these services. The objective is to forge a strong relationship with the customer by selling ‘convenience’ (through multiple services) and thus prevent the customer from moving away from the bank only on pricing concerns. Theoretically, relationship pricing is perceived as promoting customer loyalty to the bank, thus rendering the customer relatively insensitive to prices or other charges.

In all the above deposit pricing approaches, the key parameter that banks should be able to determine is their costs.

At times of sluggish deposit growth, the temptation for banks is to increase rates offered on special deposits such as CDs or new account introductions. Such strategies to increase deposit inflows would put pressure on the banks’ cost of funds and also trigger a market-wide rate war. However, over a period of time, it is possible that the increased rates would not translate into overall increase in deposits or in market share. On the other hand, the banks may be left with increased cost of funds eating into their already thin spreads.

Therefore, before hiking interest rates on some classes of deposits or going on an aggressive campaign to mobilize new deposits, there are two types of analysis that should be considered. The analysis should quantify the actual cost of new deposits and the cost of protecting existing deposits. Such analysis is typically done using the following suggested approaches—the marginal cost of funds approach and the new cost of funds approach.8

The historical average cost rate is called break even because the bank must earn at least this rate on its earning assets (primarily loans and securities) just to meet the total operating costs of raising borrowed funds and the bank’s stockholders’ required rate of return. Therefore, the bank will know the lowest rate of return that it can afford to earn on assets it might wish to acquire.

Marginal Cost of Funds Approach

Assume that Bank J has a deposit base of ₹1,000 crores, of which about ₹250 crores comprises premium deposits perceived as rate sensitive. The bank pays 5 per cent per annum on these deposits at present.

A competitor, Bank L, announces that it is prepared to pay 6 per cent on premium deposits. The objective of the competitor, of course, is to garner more deposit market share.

Should Bank J respond to the threat and revise its deposit rate?

If Bank J does not match the 100 bps rate rise, it would probably lose a portion of its deposits to Bank L. The options before Bank J are to increase the rate on the entire rate-sensitive component of ₹250 crores or leave the present rate unchanged and replace the lost deposits. Of course, Bank J has a range of options between the two extremes. For example, it could raise the rate by 50 or 75 bps instead of 100 bps. The question would be: At what cost can it replace the lost deposits as compared to increasing the rate on the entire ₹250 crores component? In short, the effective cost of protecting these balances should be compared with the incremental cost of alternative funding sources to replenish the lost funds.

An illustration of the likely impact of two extreme options is presented as follows:

| Balance (₹ in Crores) | Rate Per Cent | Expense | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial rate | 250 | 5 | 12.5 |

| Pricing option 1 | 250 | 6 | 15 |

| Pricing option 2 | 200 | 5 | 10 |

| Marginal cost/benefit | 250 | 1 | 25 |

| Marginal cost | 0.1 or 10% |

According to the above calculations, if Bank J does not raise the rate to 6 per cent, it is likely to lose ₹50 crores of its deposit base. However, it will save ₹5 crores in annual interest expense. The marginal cost of holding on to the ₹50 crores is therefore 10 per cent (₹5 crores/₹50 crores).

It doesn’t seem logical, does it? How can it cost 10 per cent to hold to a deposit that at present costs only 5 per cent to the bank?

The answer to this question is the key to making intelligent pricing decisions on rate sensitive deposit accounts.

There are actually two different costs associated with increasing the deposit rate to 6 per cent. First, Bank J must pay 6 per cent on the rate sensitive deposits of ₹50 crores that it expects to lose. This works out to an annual cost of ₹3 crores. Second, Bank J must also pay an additional 1 per cent to the remaining customers (₹200 crores) in the rate-sensitive segment. This amounts to an additional cost of ₹2 crores. This additional cost will have to be incurred even though the probability that these customers would shift their deposits out of Bank J was minimal. Hence, the total additional expense for the bank aggregates to ₹5 crores.

Now that Bank J knows that the ‘marginal cost’ of holding on to ₹50 crores of deposit is ₹5 crores in annual interest expense, which works out to an annual interest cost of 10 per cent, it can decide on whether to raise the rates.

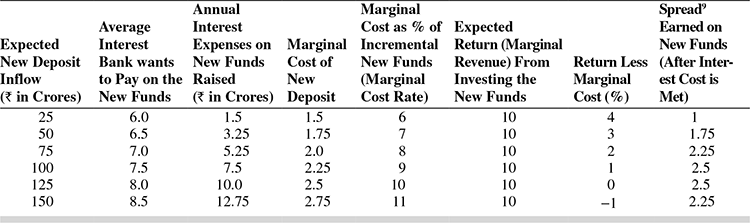

Of course, the bank will not be able to make the decision based on one scenario alone. Hence, it may want to look at various scenarios of interest rate increases ranging from 0 per cent to even more than 1 per cent if it wants to be very aggressive. It may also want to relate various probabilities of loss of deposits under each of the interest rate scenarios. Typically, the following table would result from the analysis.

| Expected Deposit Loss Protected (per cent) | Probable Rate Increases (per cent) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 0.75 | 1. | |

| 10 | 10.00 | 12.50 | 15.0 |

| 20 | 7.50 | 8.75 | 10.0 |

| 30 | 6.67 | 7.50 | 8.33 |

| 40 | 6.25 | 6.88 | 7.50 |

| 50 | 6.00 | 6.50 | 7.0 |

The above table identifies the effective marginal cost associated with increasing deposit rates with the objective of minimizing flight of deposits from the bank. For example, the incremental cost of increasing deposit rate by 0.75 per cent to protect the most volatile 20 per cent of the balances is 8.75 per cent. This effective cost is calculated as shown earlier and should be compared with the incremental cost of alternate funding sources for the bank. That is, if Bank J is likely to lose 30 per cent of its deposits due to the competitor’s offering of 1 per cent more and can replace these funds at 8.33 per cent or less, it will be better off financially than paying 1 per cent more on the entire rate-sensitive account base.

Another interpretation of the table is that as the proportion of non-rate sensitive customers in a segment increases, so does the marginal cost of paying up to retain rate sensitive customers in the segment.

This interpretation would explain why a bank would be more likely to push up its rates for CDs in a rising rate environment, rather than on its transaction accounts. The CD customers are perceived as more rate sensitive. And the more the rate sensitive customers in a segment, the less are the non-rate sensitive customers that will receive a higher rate determined in order to retain the rate sensitive customers.

The second issue that arises in the above analysis is the worth of the customers’ relationship to the bank. Using the table generated above with different rate scenarios and expected protection of deposit loss, a new question can be formed: If the bank fails to match the 6 per cent rate being offered by the competitor, what could be the maximum deposit loss? Let us assume that 20 per cent of Bank J’s customers in the segment threaten to withdraw their deposits if the bank did not match the competitor’s offering. Would the bank be willing to increase the rate to keep them? Or what if 40 per cent were to demand a rate hike? The bank’s decision would depend on how much these deposit relationships are worth to the bank, since for retaining 20 per cent or 40 per cent of its customers, the bank is actually willing to pay up to 10 per cent or 7.5 per cent, as the case may be.

A strategy that can be employed here is convincing the rate sensitive customers to move their balances into some other account in the same bank. For example, the bank can convince the customers wanting higher interest income to move to, say, higher yielding short-term deposits. Let us assume that these instruments yield an average of 5.75 per cent. The customers would be satisfied, as they are earning more on their deposits. Bank J will also be happy that it need not incur the marginal cost ranging from 6.5 per cent to 12.5 per cent to retain the relationship with these customers.

A third issue is that the bank should be satisfied that the yields it receives on assets supported by the ₹250 crores deposit accounts is more than the marginal cost of retaining rate sensitive deposits. This implies that the bank’s average yield on assets should be more than 7 per cent to 15 per cent, if the deposit rate increase contemplated is 1 per cent. For example, if only 20 per cent of the customers were rate sensitive in the segment and the bank fears that its comparable asset yield may be less than 10 per cent (see table above), it will be better off selling the assets and using the sale proceeds to fund the outgo of deposits. It is to be noted that the asset yields being used in the comparison would be net of any adjustments and servicing costs. For example, the yield on a credit card may dip from, say, 20 per cent to 12 per cent after adjusting for operational costs and charge offs.

New Cost of Funds Analysis

Let us now assume that Bank J wants to offer a new deposit product at 5.75 per cent to expand its market share. The bank is interested in tapping entirely new deposit clientele and not in conversion from its existing deposit base. The bank reviews the performance of the new product after 2 months and finds that only about a quarter of the deposits mobilized were fresh ones, the remaining being existing deposits of the bank converted to the new scheme.

The bank can use the marginal costing method as outlined above to analyse the effectiveness of the pricing strategy in attracting new customers. If the strategy has resulted more in conversions from the bank’s own existing deposit base that had earlier been sourced at a much lower cost, the bank may end up paying more as marginal cost for the new deposits, as well as merely retaining the existing market share rather than growing it. In this case too, the marginal cost of new money should be compared to the incremental cost of alternative funding sources.

Another approach helps in setting the interest rate that banks can offer for new accounts. Let us assume that Bank J now estimates that it can raise fresh deposits of ₹25 crores from the market if it offered the rate of 6 per cent offered by Bank L. Bank J also estimates that if it beat the competitor’s offering by 0.5 per cent, i.e., it offered an interest rate of 6.5 per cent, it can double the fresh deposit inflow to ₹50 crores. If Bank J pushed up the deposit rate further to 7 per cent, the fresh deposit inflow estimate would swell to ₹75 crores, while at 7.5 per cent and 8 per cent, the fresh deposits would increase to ₹100 crores and ₹150 crores, respectively.

The new deposits can be used by Bank J to invest in assets that would have an average yield of 10 per cent.

The following table illustrates the analysis using marginal cost to choose the optimum interest rate that can be offered to deposit customers.

It can be observed from the above table that the bank is able to improve its profits as long as marginal revenue exceeds the marginal cost up to a deposit interest rate of 7.5 to 8 per cent. At this point, the spread is highest at ₹2.5 crores. Beyond this point, even if the bank raises deposit rates to garner more deposits, it cannot benefit, since the average yield is estimated at 10 per cent.

Note that with the above analysis, we have gone a step further and incorporated loan or asset pricing into deposit pricing.

BOX 4.3 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DEPOSIT GROWTH AND BANK STOCK PRICES10

Research has indicated that deposit growth has a significant impact on bank stock prices. What could be the reasons for this relationship?

One, deposits lower a bank’s risk. Core deposits, which include transaction and savings accounts, time deposits and money market accounts, are a cheap source of funding. As a result, banks with a high percentage of core funding don’t have to take as much risk in their loan portfolio to generate a strong return.

Two, growing deposits help the balance sheet since equity need not be added, as in the case of loans. Banks have to raise adequate equity before they make loans.

Three, a high proportion of transaction accounts is an advantage to the bank. Transaction accounts (commonly known as CASA (Current account savings account) in India act as ‘hub’ accounts in most retail banking relationships. Industry studies show that banks are more successful in cross-selling additional financial products to their transaction account customers. The typical customer views the transaction account as the core of his banking relationship. Hence, banks get better deposits and a much larger role with these customers than with mortgages or CDs.

Finally, industry experts believe that deposits are universally valuable regardless of the environment and in most rate environments, deposit growth can pay exponentially.

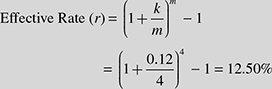

Deposits and Interest Rate Risk11

Even in the 1990s, banks considered ‘core’ deposits insensitive to interest rate movements. However, a declining interest rate environment thereafter threw up some challenges. Bank customers started looking for alternate investment avenues and banks were forced to revisit their pricing strategies. Analysts are now of the opinion that bank deposits carry some interest rate risk, measuring which is not easy in practice.

In theory, measurement of interest rate risk of deposit liabilities is similar to the techniques used for the measurement of bond investments. The steps to be followed are forecasting cash flows, balances and interest; discounting future cash flows to arrive at the present value; calculating duration12 and interest rate elasticity; and stress testing. However, the application of bond valuation methodologies to deposits would require added assumptions or information due to some unique features of bank deposits.13

Box 4.4 presents the similarities and differences between bonds and bank deposits.

BOX 4.4 COMPARATIVE FEATURES OF BONDS AND BANK DEPOSITS

Similarities

- Both bonds and deposits are financial instruments. They form part of the holders’ assets and makers’ liabilities.

- Both create interest income to the holder and interest expense to the maker.

- Bonds and some classes of deposits have a predetermined maturity date.

- Both have economic value, whether traded or not in the financial markets.

- Both can carry embedded options.

Differences

- Typically, banks are holders of bonds and makers of deposits.

- Hence, both impact the financial performance and condition of banks in similar but opposite directions (since bonds are typically assets and deposits are liabilities).

- Deposits can have stated maturity dates and also be payable on demand.

Before looking to quantify interest rate risk, we should appreciate a fundamental difference between banks and other financial firms—that under deposit insurance, banks issue a class of liabilities for which most balances are fully insured by most governments across the world. The resulting market structure could create complications for the implementation of risk management models.

First, deposit insurance insulates the deposit investor from the credit risks of the bank, which are assumed by the deposit insurer. In essence, when a bank issues a deposit it engages in two transactions: it issues a risk-free (government insured) liability to a depositor and it purchases an insurance contract from the insurer to cover the credit risks associated with the priority position of the deposit claim. Thus, the economic value of a deposit depends upon the market yield on a comparable risk-free claim, as well as the pricing of deposit insurance relative to the market pricing of credit risk.

Second, for small depositors, bank search and switch costs, convenience value, information costs and simply limited alternatives make adjusting to changing market conditions difficult.14

The impact of interest rate changes on a bank can be viewed from two possible perspectives—the earnings perspective and the capital perspective.

For viewing the impact from an earnings perspective, we should remember that bank deposits include some that have no direct interest cost for the bank and some that bear interest at rates that could have been administered by managerial decisions not directly linked to market rate movements. Also, research finds that retail deposit markets are characterized by sluggish behaviour in both interest rates and deposit issuance in response to changing market conditions. Since, by definition, competitive markets respond immediately and completely to changing circumstances, it appears that there is no comparable competitively priced instrument that could be used as a reference for deposit profit.

Hence, to measure the ‘earnings-at-risk’ related to deposits, the way in which deposit interest expense reacts to changes in market rates must be known (or assumed). Some movements in market rates may be too insignificant to have any perceptible impact on deposit interest rates, while other market rate movements may be large enough to influence managerial pricing of deposit rates. Such changes in pricing are bound to impact both the deposit balances with and the cost of deposits for the bank.

From the longer term perspective, while demand deposits, by definition, are repayable on demand, much of these deposits could also be held as ‘idle balances’ by customers who prefer convenience or financial security or liquidity. These idle balances form part of the ‘core deposits’ for the bank. Interestingly, research has found that banks’ access to such core deposits forms one of the foundations of ‘relationship lending’, where banks can afford to fund their key borrowers at less than market rates, in order to sustain their relationship.15

Since all types of deposits do not react in a similar fashion to market rate changes, current interest rate shocks translate into changes in profitability over time thus impacting the bank’s ‘value’. From the ‘capital’ perspective, the current economic value of deposits held by a bank is typically measured by the current interest rate paid on the deposits and the cost of alternative funding sources for the bank based on assumptions of maturity or repayment of these balances. For better understanding, if we treat demand deposits as continuously-maturing financial contracts, the existence and magnitude of current deposit base is an indicator of profitable deposit growth in future. Hence, ‘equity at risk’ related to deposits for the bank would be measured by the current economic value of its core deposits and estimates of how the core deposits would change with changes in market rates.

SECTION IV

BANK LIABILITIES—NON-DEPOSIT SOURCES

Over the last three decades or so, banks have been increasingly turning to non-deposit funding sources (also called ‘wholesale funding’ sources).

For example, in the United States of America, prior to the 1970s, domestic deposits made up 80 per cent or more of total bank assets. In the 1970s, however, financial markets changed in response to inflation and higher interest rates, resulting in banks taking on larger amounts of non-deposit liabilities. By 1980, domestic deposits made up only 64 per cent of total assets. During the 1990s, banks’ reliance on domestic deposits for funding continued to decrease as banks increased their usage of borrowed funds, foreign deposits and other liabilities. At the end of 2000, the ratio of domestic deposits to total assets stood at 55.6 per cent. Banks had come to rely more heavily on foreign deposits, fed funds, repurchase agreements, Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances (described in Annexure I ) and other forms of borrowing than they did during the first few decades of the FDIC’s existence.16

The Funding Gap

The funding gap is calculated as the difference between current and projected credit and deposit flows. If the difference shows the projected need for credit exceeding the expected deposit flows, the bank has to raise additional resources either from deposit or non-deposit sources. If the difference shows the projected credit requirements falling short of resources, the bank will have to find profitable investment avenues for the surplus resources.

Assume, Bank X has made the following projections for the ensuing week:

- New credit offtake: ₹300 crores

- Drawings by existing borrowers from credit sanctions already made, but not utilized: ₹500 crores

- New deposits inflow: ₹700 crores

- Planned investments in government and corporate securities: ₹400 crores

The projected funding gap for Bank X would be:

less

The funding gap for Bank X for the following week is expected to be ₹500 crores.

If Bank X wants to bridge the funding gap with non-deposit sources, it would have to weigh the following factors in choosing among the various options available.

- The relative cost of each funding source.

- The relative risk of each funding source.

- The period for which the funding is required.

- The size of Bank X.

- The regulations governing each of the funding sources being considered.

Other factors held constant, management will seek out the lowest cost non-deposit funding sources available, subject to availability and the expected interest rate risk.

Let us further assume that Bank X has the following options to bridge the funding gap of ₹500 crores.

| Alternative Funding Source | Market Interest Rate (per cent) | Cost of Access (per cent) |

|---|---|---|

| Central bank funds | 6.0 | 0.10 |

| CDs | 8.0 | 0.20 |

| Foreign funds | 10.0 | 0.30 |

| Other money market funds | 6.5 | 0.25 |

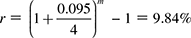

If Bank X plans to raise ₹600 crores this week, of which ₹500 crores will be used to meet the investment and loan commitments made, the effective annual cost of each of the sources would work out as follows:

| Alternate Sources of Funds | Market Rate | Cost of Access | Effective Cost of Funds* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central bank funds | 0.06 | 0.001 | 0.0732 |

| CDs | 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.0984 |

| Foreign funds | 0.1 | 0.003 | 0.1236 |

| Commercial paper | 0.085 | 0.005 | 0.108 |

| Other money market funds | 0.065 | 0.0025 | 0.081 |

*Effective cost of funds is worked out as = [(market rate × 600) + (cost of access × 600)]/500

Bank X will have to compare the effective cost of each type of funds with the cost of getting fresh deposits in the market and the yield it expects to earn on deployment of the funds into loans and investments. It can also consider a mix of various sources of funds, subject to availability and other factors listed above.

The Indian Scenario

Non deposit sources of funds

Banks in India access non deposit sources of funds as “borrowings” from both domestic and international markets. Short term funds are acquired from the ‘Money Market’ and long term funds from the capital and international markets. Non deposit funding sources are usually accessed to augment deposit sources or for a particular purpose, such as capital requirements.

Some prominent money market sources of funds – banking sector securities17

The money market is a market for short-term financial assets that are close substitutes of money. The most important feature of a money market instrument is that it is liquid and can be turned into money quickly at low cost and provides an avenue for equilibrating the short-term surplus funds of lenders and the requirements of borrowers. Maturities in the money market range from overnight to one year.

We have learnt in the preceding chapters that the central bank aligns money market rates with the policy rate in the context of monetary management.

a. Call, notice and term money market

The call/notice money market forms an important segment of the Indian Money Market. Under call money market, funds are transacted on an overnight basis and under notice money market, funds are transacted for a period between 2 days and 14 days. When borrowing/ lending takes place for a period exceeding 14 days, it is called term money.

Scheduled commercial banks (excluding RRBs), co-operative banks (other than Land Development Banks) and Primary Dealers (PDs), are permitted to participate in call/notice money market both as borrowers and lenders. Other financial institutions are not permitted to transact in the call money market

Limits are fixed for borrowing in the market. However, interest rates are determined based on demand and supply of funds in the market. Mode of calculation of interest payable would be based on the methodology given in the Handbook of Market Practices brought out by the Fixed Income Money Market and Derivatives Association of India (FIMMDA).

Please recall that the weighted average Call rate (WACR) is the operating target of monetary policy of RBI, reflecting the liquidity in the banking system.

Other operational details about the market are available on the RBI website.

b. Certificate of deposit (CD)

Certificate of Deposit (CD) is a negotiable money market instrument and issued in dematerialised form or as a Usance Promissory Note against funds deposited at a bank or other eligible financial institution for a specified time period.

CDs can be issued by (i) scheduled commercial banks (excluding Regional Rural Banks and Local Area Banks); and (ii) select All-India Financial Institutions (FIs) that have been permitted (by RBI) to raise short-term resources within the limit fixed by RBI.

Banks have the freedom to issue CDs depending on their funding requirements.

Minimum amount of a CD should be Rs.1 lakh, i.e., the minimum deposit that could be accepted from a single subscriber should not be less than Rs.1 lakh, and in multiples of Rs. 1 lakh thereafter.

CDs can be issued to individuals, corporations, companies (including banks and PDs), trusts, funds, associations, etc. Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) may also subscribe to CDs, but only on non-repatriable basis.

The maturity period of CDs issued by banks should not be less than 7 days and not more than one year, from the date of issue.

CDs are issued at a discount on face value. Banks / FIs are also allowed to issue CDs on floating rate basis provided the methodology of compiling the floating rate is objective, transparent and market-based. The issuing bank / FI is free to determine the discount / coupon rate, that is, the rate is dependent on supply of and demand for funds in the market. Please recall that we had mentioned in a preceding chapter that when banks were flush with funds after demonetization, there was a period in which CDs were not issued.

Banks have to maintain appropriate reserve requirements, i.e., Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) and Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR), on the issue price of the CDs.

Banks / FIs have to account the issue price under the Head “CDs issued” and show it under “Deposits”.

Fixed Income Money Market and Derivatives Association of India (FIMMDA) prescribes, in consultation with the RBI, operational flexibility for smooth functioning of the CD market. More operational details can be found in the Master Directions from the RBI and the RBI website.

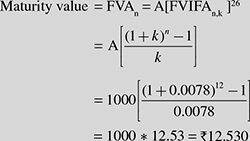

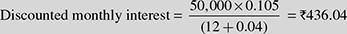

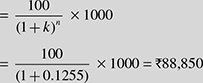

The numerical example provided in Illustration 4.1 clarifies on pricing of CDs.

ILLUSTRATION 4.1

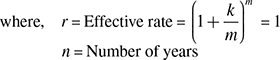

A certificate of deposit with a face value of Rs.10,00,000 is issued at a discount price of Rs.9,70,874 with a term of 6 months. CRR is 4.5% and stamp duty is 0.125% per quarter. What is the cost to the bank and yield to the investor respectively ?

Solution:

- Yield to Investor = ((1000000-970874)/970874)*(12/6) = 6%

- Cost to bank = ((1000000-970874)/(970874*0.955))*(12/6) = 6.3%

Note that the bank’s cost takes into account that funds remaining after CRR maintenance alone can be reckoned for the calculation

If Stamp duty is added, the cost increases to 6.78% (6.3% + .125% *4 quarters) to arrive at annual cost

c. Repo

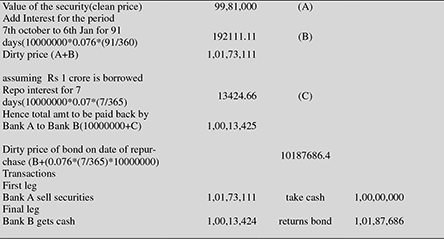

The repo and reverse repo are important instruments in the money market. The Chapter on Monetary Policy has details about various kinds of repo and their operations. The numerical Illustration 4.2 below shows the transactions in a repo between two market participants.

ILLUSTRATION 4.2

Bank A proposes to borrow on Jan 7, 2017 Rs 1 crore from Bank B for 7 days at 7% repo rate.

The security for this transaction is 7.6% 2020 G secs. The current price of this security with face Value Rs 1 crore is Rs 99.81.lakhs.

It pays out interest semi annually on 7th april and 7th october.

What will the transactions be?

Annexure I. contains a brief description of select non deposit sources of funds for banks in the USA.

Long term borrowing by banks18

- Issuing bonds in the domestic market.

- Issuing bonds in international market - Masala bonds have been briefly described in the earlier chapter, and a case study on Masala bonds is being included in the Annexure to this chapter.

- Perpetual Debt Instruments (PDI) qualifying for inclusion as Additional Tier 1 capital.

- Debt capital instruments qualifying for inclusion as Tier 2 capital.

(PDI and debt capital instruments can be issued under Basel III regulations. Details and explanation can be found in the Chapter on Capital adequacy).

- Borrowing in foreign currency is not permitted except for specific purposes, which are laid down by RBI and updated when required.

Are Non-Deposit Sources More Costly and Risky? Borrowings from the market are generally perceived to be more expensive than deposit sources. Where banks tend to rely on borrowings to fund their lending operations, they are exposed to market risks—the cost of such borrowings and their availability may also fluctuate. In contrast, there are quite a large number of deposit customers who put an extremely high value on the safety and accessibility of insured deposits and keep their money with banks even when alternate investments offer more attractive returns.

Generally depositors, whose deposits with banks are insured, may not be very concerned about the financial health of the bank they invest in. However, other lenders who do not enjoy insurance protection would seek interest rates commensurate with the risk profile of the borrowing bank and also expect the bank to match market interest rates.

However, apart from the cost aspect, wholesale funding is not without its risks. Non-deposit sources lack the stability of deposit, especially core deposit sources. Banks accessing wholesale funding markets must develop the capability to not only access the appropriate type of funds at short notice, but also repay them on due date. This implies that these banks would have to ensure back up measures, such as short-term investment in government securities, which can be sold at short notice. Such measures may affect the banks’ profitability since liquid securities yield lower returns. Banks may also have to invest in personnel with the requisite expertise in managing sourcing and repayment of such funds in the market.

On the other hand, such wholesale borrowings may be cheaper at the margin than deposits, even if the rates paid on non-deposit funds are actually higher. One reason would be the lower transaction costs for raising bulk wholesale funds, which banks often raise with a mere phone call. In doing so, banks save on branch, personnel and system costs. Another reason would be that banks need not alter their deposit rates for accessing wholesale funds. As discussed in the earlier section, if a bank has to attract more deposits only by offering higher rates, the overall cost of funds for the bank might increase substantially.

In fact, banks have been finding new funding sources from the money markets, long term and international markets. Of late, loan sale19 (such as securitization) mechanisms have also become a popular means of augmenting banks’ liquidity. Moreover, banks active in the non-deposit funding market are increasingly finding that some wholesale fund lenders are willing to sculpt their repayment schedule to banks’ cash inflows from asset liquidation.

SECTION V

BANK DEPOSITS IN INDIA—SOmE ImPORTANT LEGAL ASPECTS

‘Banking’ Defined

Banking is defined under Section 5(b) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. It means ‘accepting, for the purpose of lending or investment, deposits of money from the public, repayable on demand or otherwise and withdrawable by cheque, draft, order or otherwise’. Some important interpretations follow from the above definition.

- ‘Banking’ means performing two essential functions of: (a) accepting deposits from the public; and (b) lending or investing the deposits. It, therefore, follows that if the purpose of accepting deposits is not to lend or invest, it cannot be called ‘banking business’. For example, companies accepting deposits from the public for financing their business cannot be said to be doing banking business.

- The banker accepts deposits of ‘money’ from the ‘public’ that offers its money as deposit. But it is not mandatory that the banker has to accept all such deposits offered. The banker can refuse to accept money from undesirable elements of society such as thieves, smugglers or terrorists.

- The deposit could be payable on demand (such as transaction deposits, savings deposits) or payable after a fixed term as in the case of term deposits. The essential point to note here is that the bank need not repay the deposit without a ‘demand’ being made by the depositor, even after expiry of the contracted period of deposit. Withdrawal of deposit balances are to be done through cheques, drafts, etc. This implies that a written demand is necessary to end the contract and seek repayment of the depositor’s balances.

It is thus clear that accepting deposits and maintaining deposit accounts is the core activity of any bank.

Annexure II provides a brief overview of some of the important legal provisions that affect banking operations in India.

Who is a Customer?

You will be surprised to know that the term ‘customer’ of a bank is not defined by law. Typically, any person or entity transacting with a bank through a deposit or borrowing account is considered its customer.

From a summary of past important judicial decisions, the following characteristics can be attributed to a customer.

- A customer is one who maintains a deposit account with the bank.

- Duration of the account is immaterial.

- State of the account, that is whether it is in debit or credit, is immaterial.

- Banker–customer relationship would exist even between two banks if one maintains accounts with the other and cheques, etc. are collected through that account.

- Merely visiting a bank frequently for purchasing a draft or for encashing a cheque, etc. does not confer on the visitor the status of a customer, i.e., maintenance of a deposit account is mandatory to be eligible to be termed a ‘customer’.

- A customer of one branch does not automatically become a customer of another branch of the same bank where he does not maintain an account.

- Even an agreement to open an account would make a prospective depositor a customer of the bank.

In modern banking, the vital determinant of the ‘customer’ status of a person or entity is the nature of dealings with the bank. Such dealings should be in the nature of ‘banking business’. Accordingly, the person or entity that does not deal with the bank in respect of its core banking functions—accepting deposits and lending or investing the deposits—but avails of other services from the bank, is not deemed a ‘customer’.

TEASE THE CONCEPT

Which of the following transactions indicate that X is a customer of Bank A?

- deposits cash with Bank A to be credited to the Insurance company on whose behalf A accepts payments.

- deposits cash to purchase a demand draft from Bank A.

- X brings a cheque in his name to Bank A for encashment.

- X brings a cheque in his name to Bank A for crediting to his savings account with A.

- X deposits documents in Bank A’s safe deposit vault.

The primary relationship between a banker and customer is therefore of ‘debtor and creditor’. However, under special circumstances and on the customer’s request, the banker can also act as ‘trustee’ (e.g., holding a designated deposit of the customer for the purpose of paying a third person or holding the customer’s valuables in safe deposit lockers) or as an ‘agent’ (e.g., buying and selling securities on behalf of the customer, making insurance and utilities payments on due date as specified by the customer).

Who is Eligible to be a Customer?

In their role as financial intermediaries, banks are bound to accept public savings as deposits. However, they can enter into legally valid contracts for this purpose only with certain sections of the society.

Thus, deposit accounts can be opened only by those who (a) are capable of entering into a valid contract, (b) follow the banks’ prescribed procedures while entering into the contract and (c) accepts the banks’ terms and conditions while doing so. Thus, banks retain the right to reject an application for opening deposit accounts.

The legal position of some special classes of banks’ customers is outlined in Annexure III.

General Guidelines for Opening Deposit Accounts

The importance of proper introduction and verification of new deposit accounts has been embodied in the Know Your Customer (KYC) guidelines of the RBI.20 These guidelines advise banks to put in place systems and procedures to prevent financial frauds, identify money laundering and suspicious or criminal activities and for scrutiny/monitoring of large value cash transactions, including transactions in foreign currency.

The KYC guidelines of the RBI are modelled on international best practices. Both the World Bank and the IMF have been involved in international efforts to strengthen financial sector supervision and promote good governance, in an effort to reducing financial crime and enhancing the integrity of the international financial system. Since 2001, anti-money laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) measures have come into sharper focus. Both the World Bank and the IMF have worked closely with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on money, the standard setting body in this area, to develop a methodology for assessing the observance of international standards on the legal, institutional and operational framework for AML–CFT.