Chapter 11

Real-World Tasks

By now you may find your eyes glazing over at the scale of the project you have undertaken. However, Google Analytics is one of the easiest web analytics tools to configure, use, and understand. This chapter includes real-world examples of tasks most web analysts regularly need to perform. By presenting them, I hope to demystify the complexities of web analytics. As long as you dedicate the time and resources, you will find that this isn’t rocket science. Even better, you will have a profound impact on the performance of your organization’s website.

The tasks presented here are not intended to be an exhaustive or definitive list; rather, their purpose is help you obtain useful information you can act on. Acting on your data is the single most important aspect of web analytics, yet it is this aspect that most people stumble with.

In Chapter 11, you will learn:

- To identify and optimize poor-performing pages

- To measure the success of internal site search

- To optimize your search engine marketing

- To monetize a non-e-commerce website

- To track offline marketing

- To use Website Optimizer

Identify and Optimize Poor-Performing Pages

With all that visitor data coming in, one thing you will want to do is optimize your pages for the best possible user experience. Often the improvements are straightforward—for example, fixing broken links, changing landing page URLs to match the visitor’s intent, or aligning page content with your advertising message. But which pages should you optimize and how? If your website has more than a handful of pages, where do you start?

Traditionally for web analytics solutions, identifying pages that underperform from the plethora of other pageview data has been a difficult task. However, Google Analytics has several resources and reports to help you. The following highlights the two areas I most commonly turn to:

- Landing pages (bounce rates)

- Funnel visualization

Using Landing Pages (Bounce Rates)

As the name suggests, the Content Site Content Landing Pages report shows the most popular entrance pages for your visitors (Figure 11-1). Note the weighted sort that I have applied to ensure that the volume of traffic—that is, visits—is taken into account when sorting by bounce rate (weighted sort is discussed in Chapter 4, “Using the Google Analytics Interface”).

Figure 11-1: Landing Pages report

For this report, the bounce rate is the key metric; if visitors are arriving at the landing page and then leaving the site after viewing only that one page with no other action or event triggered, it is poor engagement. If a landing page has a high bounce rate, it means that the content of that page did not meet the visitors’ expectations. Beyond looking for page errors, you need insight as to what the visitors’ expectations were, which means looking at the referral details.

Note: My definition of a single pageview with no other action or event constituting poor engagement assumes you are not writing the perfect one-page article. Even if you are, you should be soliciting a further action from your visitors, such as, for example, click to rate, add a comment, a subscription, a share, or a Like on their social network and so forth. If you do not do this, how will you define success? In fact, how will you ever know if your efforts are being appreciated or worthwhile?

What constitutes a high bounce rate is discussed in the section titled “Content Creator KPI Examples” in Chapter 10, “Focusing on Key Performance Indicators.” My rule of thumb is to define high as a bounce rate of greater than 50 percent for nonpublisher websites. Publishing sites such as newspapers, book publishers, and blogs that do not require a user login generally have higher bounce rates—there is simply less incentive for visitors to click through.

Exercises for Bounce Rate Optimization

Once you have a list of your 10 worst-performing landing pages—as defined by high bounce rate weighted by traffic volume, bring in your marketing or agency team to discuss improvements. Include a member of your sales team and your customer service department in the meeting, and ask them to bring a list of the five most common questions customers ask. Then spend a morning brainstorming. The following describes a three-step approach for doing this.

Map marketing campaigns to landing pages As an initial exercise, ask the teams to map out the campaigns that should be driving visits to these landing pages. I emphasize the word should because sometimes something outside of your organization’s control—for example, a news story—can be driving your traffic and your team should also be aware of these. Hopefully, a strong overlap is apparent between your team’s knowledge and where your visitors are coming from. That is, the marketing team has campaigns running that are targeting the pages on your list, including organic search engine optimization campaigns. The important lesson from this exercise is in understanding why visitors arrive on these landing pages and what are the drivers for their doing so.

Check that visitor expectations align with landing page message In your next meeting, discuss how to improve visitor engagement; that is, how to encourage visitors to click through beyond their landing page and explore your website further, therefore decreasing the bounce rate. As a team, view each landing page from your list in a browser. The important question to answer is: Does the landing page match the expectations of the marketing campaigns for it? Perhaps the pricing is wrong, or a special offer is outdated? Are there any errors—images not loading, spelling or grammatical errors? Are your landing pages slow to load? All of these are very off-putting to potential customers.

Tip: When you view your landing pages in a browser, ensure that you use an external route to your server, one that goes via the Internet as if you are a regular visitor and not via your local network. That way you will view your pages as your visitors do—experiencing the same errors and time delays. Also, ensure that you have cleared your browser’s cache.

Define the landing page purpose and optimize. For your third team meeting, examine the purpose of each landing page. All landing pages have a purpose, and that is to help drive goal conversions. This is why you should not use your home page as a campaign landing page—it is too generic and ill focused. The purpose of your home page is to define your brand, not drive conversions directly. An obvious purpose is to present product information, but it may also be providing trust and credibility for your organization as well as managing the visitor’s expectations.

Summary of Methodology

The exercises just described are excellent for getting your teams thinking about the purpose of a page in relation to its marketing rather than focusing on its marketing in isolation, which is often the case. Bounce rate is a powerful metric for understanding content performance, and I find it is often underutilized. The following is a summary of the points discussed in this section:

- Use weighted sort to obtain your list of poor-performing landing pages from the Content Site Content Landing Pages report. Focus on the top 10 worst performing landing pages by bounce rate, and bring in your marketing team and agency for a meeting.

- Map out the current campaign strategy for the listed pages. Understand what should be driving traffic to them. See if this matches your report. For example, if 50 percent of your marketing budget for a landing page is for paid search, does that landing page receive approximately 50 percent of its traffic from that source?

- Load each landing page in your browser, and check what the visitor’s expectation will be. Does the messaging of the campaign align with that of the landing page? Are there any errors or omissions? Do pages load quickly? Improve as required. Ensure that your home page is not being used as a campaign landing page. If it is, assign a dedicated page for it, or build one.

- View the content of each landing page and determine how to increase its engagement. Ask the team what its purpose is in relation to your goals and how the purpose can be strengthened. Add or modify the conversion contributing factors.

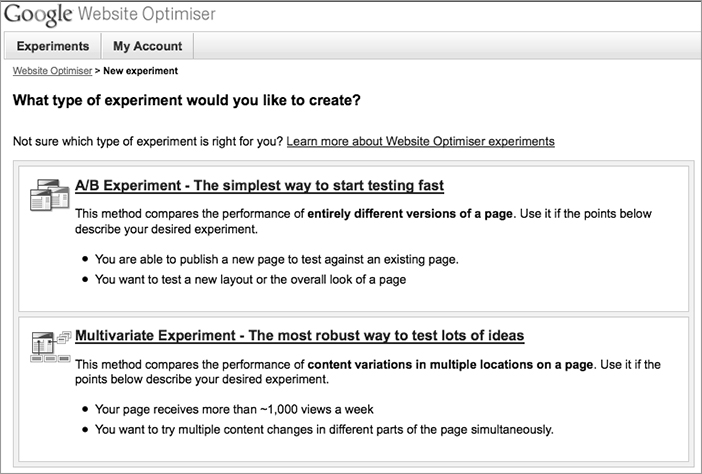

- Where page improvements are not obvious, consider showing alternatives to a small sample of your visitors by using an A/B or multivariate testing tool—see “An Introduction to Google Website Optimizer” later in this chapter.

Conduct this entire exercise quarterly. For example, you may select 10 pages in the first quarter, followed by the next 10 in the second quarter, and so forth. Consider that most websites obey the 20/80 rule; that is, 20 percent of content is responsible for 80 percent of revenue or leads. Therefore, you should find your optimization efforts being rewarded quickly.

For assessing bounce rates in detail, the key dimensions to review are the entrance sources and entrance keywords—because these refer to your visitors’ expectations before arriving on your website. Exercises for doing this are discussed next.

Assessing Entrance Sources

As the term suggests, entrance sources are the referring websites and campaigns that lead visitors to your site—for example, search engines, paid advertising, social networks, affiliates, and email links. An example report for a website home page is shown in Figure 11-2.

Figure 11-2: Entrance sources report for a specific landing page

Discuss this report with your marketing team by considering the following perspectives:

- Offline marketing initiatives

- Paid search campaigns

- Search engine optimization (SEO)

- Social network participation

- Email marketing

In the report shown in Figure 11-2, the source labeled (direct) in row 3 could be the result of offline marketing efforts whereby people have seen your ad and remembered your web address. If you observe a high bounce rate from this source, then look at how you are targeting visitors by offline methods. A common mistake is to send visitors for a specific campaign to a generic home page, leading to poor traction with the visitor. Later in this chapter I discuss how to overcome this (see “Tracking Offline Marketing”).

Note: The label (direct) will also be applied to visitors who bookmark your website (add to favorites) and any non–web referral link that has not been set up correctly, such as email links, mobile apps, and embedded links within PDF files. To ensure that these are tracked, refer to “Campaign Tracking” in Chapter 7, “Advanced Implementation.”

From the report shown in Figure 11-2, identify any paid search campaigns. Pay-per-click advertising is an excellent way to target search engine visitors with a specific message (ad creative) and specific content (landing page URL). Any high bounce rates observed from these sources should be investigated immediately because they reflect poor targeting or a misaligned message. A common mistake is using time- or price-sensitive information in your ad creative that is outdated when the visitor clicks through. Therefore, you should review your ads carefully.

In addition, are your ad landing page URLs targeted for your campaigns? Avoid the use of your generic home page as a landing page URL—use a more specific one. Another area to look at is how you target your visitors with geotargeting; for example, do your pricing and delivery options match the expectations of visitors from different locations? These are discussed later in this chapter in “Optimizing Your Search Engine Marketing.”

From an SEO perspective, think in terms of the visitor experience because ultimately this is what search engines are trying to emulate with their ranking algorithms. For high-bounce-rate pages from organic search visitors, view the source code and read the content within the HTML <title> and <meta name="description"...> tag sections. Are these in alignment with the rest of your page content? This is important because it is the only information about your organization a visitor sees on a search engine results page—the text of the clickable link is taken from your page title tag, while the snippet of text underneath is taken from your meta description tag. Hence, these are important qualifiers for visitors before clicking through to your site. Discuss with your marketing team making adjustments to these HTML tags. Most Content Management Systems (CMSs) allow you to do this without having to edit source code.

Also consider link referrals from other websites. Following a link from another website that turns out to be out of context is obviously a poor experience and waste of time for the visitor (it can also have a negative impact on your SEO rankings). If you find referral links with high bounce rates, use the Traffic Sources Sources Referrals report to investigate further. From there you can identify the referring site and view the exact page that visitors clicked through to arrive on your website. Sometimes a simple, polite email to the webmaster of the referring site can pay you dividends. Specify that you want to ensure that links are in context and point to a relevant, specific landing page on your website. Provide any necessary details in your email.

Assessing Entrance Keywords

The Entrance Keywords report focuses on those visitors who have used search engines to arrive on your website—both paid and nonpaid (organic) search engines. In effect, this report is direct market research—visitors are informing you of exactly what content they expect to see on the page they arrive at on your site. Click the Keyword dimension shown in Figure 11-2 to extend the report, as shown in Figure 11-3.

Figure 11-3: An Entrance Keywords report

As with the Entrance Sources report, high bounce rates here (greater than 50 percent) are an indicator that something may be amiss with your online marketing. Assuming your web server performance is not an issue, look at your visitor targeting, message alignment, and page relevancy, as described in the previous section.

Following this, consider the Entrance Keywords report as an opportunity to build page content around the listed keywords. For example, in Figure 11-3, row 6 for www.advanced-web-metrics.com shows a search term of web analytics ebook, yet I had not considered the term ebook in my content—instead I had been referencing the terminology as PDF. I now know ebook is an important term to my visitors and so have been including it ever since on relevant pages.

This is an example of where viewing low-bounce-rate pages can also provide important information (row 6 shows a relatively low bounce rate). Generally speaking, you will focus your efforts on analyzing high-bounce-rate pages because these are the ones killing your visitors’ user experience. However, it’s important to look at both ends of the spectrum when searching for insights.

Funnel Optimization Case Study

As discussed in Chapter 5, “Reports Explained,” funnel analysis is an important process that helps you recognize barriers to conversion on your website, including the checkout process. I have often seen how understanding the visitor’s journey within a website, followed by subsequent changes to improve the process, can lead to dramatic improvements in conversion rates and therefore the bottom line. For example, the fourfold increase in bookings for a travel website, shown in Figure 11-4, was the result of the following funnel optimization case study.

Figure 11-4: Conversion rate improvement for a travel website before and after funnel optimization

Billions of Dollars Left Abandoned

According to 2010 data from Forrester Research Inc.

www.internetretailer.com/2010/09/28/key-profit-indicators-point

the average shopping cart abandonment rate for US online retailers is 55 percent. In other words, the transaction revenue obtained by site owners is approximately half of what customers are willing to spend and are in the process of spending. That is, on average US retailers leave $1 of the money on the table for every $1 collected! It is an incredible amount statistic when you consider that US online retail is predicted to be worth $279 billion by 2015. See

Schematic funnel shapes and their meanings are discussed in the section “What Funnel Shapes Can Tell You” in Chapter 8, “Best Practices Configuration Guide.” An ideal funnel process would schematically look like Figure 11-5, where there is a gradual decrease in visitors (width of funnel) because of self-qualification through the various steps (height of funnel). The process of self-qualification could be by, for example, price, feature list, delivery location, stock availability, and so on.

Figure 11-5: An ideal schematic wine goblet funnel shape

For this travel website case study, Figure 11-6 schematically illustrates the checkout process (booking a vacation).

The customer follows these steps:

1. Search for a vacation rental.

2. View search results.

3. Check the availability of rental.

4. Book the trip.

5. Confirm the booking.

6. Make payment.

7. Receive confirmation of payment.

Figure 11-6: Schematic funnel process for the travel website case study

Figure 11-7 is the actual funnel process reported in Google Analytics for the travel website using the Conversions Goals Funnel Visualization report.

Note: I am quite biased when it comes to travel websites. On the whole, they tend to be poorly built from a user’s viewpoint. They are pretty, with a lot of colorful images and inspiring photographs, but I never seem to have a good experience when it comes to actually booking my travel plans, let alone a great one. However, as a wise person (@AnderssonSara) once said to me, “Your biggest obstacle is also your greatest opportunity.”

Figure 11-7: Funnel Visualization report for the travel website case study (page names obfuscated for anonymity)

Issues with the Funnel Presented

The steps from the funnel visualization in Figure 11-6 are discussed in the context of the following six issues, indicated by the large letters in Figure 11-7:

Issue A The most obvious metric that stands out in Figure 11-7 is the end conversion rate—a woefully poor 0.30 percent. Put another way, 99.70 percent of all visitors abandon the booking process. Considering the cost of acquiring those visitors by both paid and nonpaid search, that means a very, very negative return on investment.

Note: Although this funnel example is an extreme case, it never ceases to amaze me that online purchase rates can be so low and are accepted as such. For example, the e-tailing group 10th Annual Merchant Survey, April 2011, shows that the most common US merchant conversion rates are between 1.0 and 2.9 percent (see the chart in Figure 1-5 in Chapter 1, “Why Understanding Your Web Traffic Is Important to Your Business”). Surely we can do better than having 97 plus percent of visitors leave a website without conversion? I hope that having read this far, you will agree that it is laudable and entirely possible to improve this percentage significantly.

Issue B Looking at the entire booking process, the length of the funnel, at seven steps, appears overly long. From user experience experiments, it is widely known that users do not like long checkout processes. That’s obvious to anyone who uses the Web! The most effective method to reduce cart abandonment is to streamline the number of steps in the process, and this is applicable here. On inspection, step 5 (confirm the booking) is superfluous because all booking details are displayed at each preceding step.

Issue C The process begins with the search_text.asp page. This is the page where visitors search for their vacation rental (hotel, villa, apartment). From this page, 30 percent drop out of the funnel.

Issue D Following step 1, the search results page (step 2) loses 60 percent of remaining visitors; over half of these (13,313) exit the site completely.

Issue E Looking at the check-availability page (step 3), 83 percent of remaining visitors drop out of the funnel; again, the vast majority are site exits (60 percent). This is clearly a pain point and should be red-flagged as a problem page.

Issue F The next steps in the system have similar problems, but the killer is step 6, which is when payment details from the visitor are requested. Out of the 725 visitors who have had the stamina and persistence to get through what is obviously a difficult process, 80 percent of them (580) abandon at this final step; the vast majority leave the website completely.

Seeing the result of these issues represented schematically, we observe a funnel shape more like what is shown in Figure 11-8, with two clear pain points in the process, step 3 and step 6, that lead to large-scale abandonment.

Figure 11-8: Stacked champagne glass schematic funnel shape

Action Points from the Funnel Optimization

Understanding the real-world funnel process of Figure 11-7 and its problems took less than one hour because the data is so clearly presented. Of course, correcting such issues obviously takes longer; you need to understand why this happened. This is something that web analytics tools cannot do; they cannot tell you why visitors are abandoning your booking process.

To address this, you could deploy a feedback system—a survey that pops up when a visitor abandons the booking process or leaves your website. Example survey tools include Clicktools, Kampyle, SurveyMonkey, and UserVoice. However, if your visitors are leaving because of a bad experience, they usually won’t want to spend further time on your site explaining what went wrong. That said, any feedback from visitors within your shopping cart system who are abandoning is gold dust and worth pursuing. See Chapter 12, “Integrating Google Analytics with Third-Party Applications,” for an example integration with the Kampyle feedback system.

Putting aside having to deploy a feedback survey system, a little lateral thought and visiting your own website as if you were a potential customer can go a long way. For example, in this scenario I focused on steps 3 and 6, where the vast majority of visitors were abandoning the booking process. This led to the development of four key recommendations for improvement:

Improve the availability checker page. Step 3 (the availability checker) indicates either a total lack of accommodation availability, in which case the website owners should turn down the visitor acquisition tap and save marketing budget, or a malfunction in the process of selecting available dates.

Lack of availability was not an issue. When I viewed the availability checker manually, no errors were found, but the process was quite clunky and difficult to interpret. For example, dates themselves were nonclickable. Instead, date-selection controls were located below the fold of the page—that is, not visible without scrolling down.

Correct the layout of the payment form. Step 6 (the payment form) required some additional thought. Although the form was considered to be overly long at seven steps, it did not make sense that such persistent visitors would bail out en masse at the penultimate step (visitors were aware of their progress by the numbering of the steps—for example, with the heading “Step X of Y”). To test for problems, I tried the process of booking a vacation myself.

What I immediately discovered when clicking to submit my dummy payment details was an error page. In addition, the error page did not indicate what caused the problem. Using the Back button, I checked all the required fields and tried again—same error page, no message indicating what the error was. This process was repeated many, many times with no further insight. It really did appear to be a mystery as to why I could not complete my payment.

In fact, the problem was staring me in the face. The credit card type (Amex, Visa, MasterCard) was preselected as Amex by default. However, the HTML drop-down list for selecting the card type was not aligned with the other form fields—it was to the extreme right of the page, while everything else was left aligned.

Despite repeatedly testing the payment system and staring frustratedly at the page, I simply didn’t see the right-aligned card selector. I was filling in all my details correctly and hadn’t noticed the default setting for the credit card as Amex while I was using Visa. In fact, I hadn’t noticed the card type drop-down list at all.

Now the explanation of large-scale abandonment at step 6 is clear. Visitors were receiving the error page, which was probably the straw that broke the camel’s back after such a difficult and torturous booking process, and so they simply abandoned the site.

Streamlining the Checkout Process

Although selecting your card type on a payment form is almost always a manual process, it is possible to automate this and remove any potential errors. You can do this by using the initial digits of the card number, as shown in the following table:

| Card Types | Prefix | Number of digits |

| American Express | 34, 37 | 15 |

| Diners Club | 300 to 305, 36 | 14 |

| Carte Blanche | 38 | 14 |

| Discover | 6011 | 16 |

| EnRoute | 2014, 2149 | 15 |

| JCB | 3 | 16 |

| JCB | 2131, 1800 | 15 |

| MasterCard | 51 to 55 | 16 |

| Visa | 4 | 13, 16 |

Track error pages. Part of the difficulty in identifying the problem visitors were experiencing in step 6 was that the subsequent error page was not being tracked. Had it been, using the methods described in Chapter 9, “Google Analytics Customizations,” the investigation could have taken place much more quickly.

Show clear instructions in your error pages. Even if an investigation into the low conversion rate had not been undertaken, visitors could have corrected the payment problem themselves—that is, if they were told what the problem was. Clearly this is not a solution to the problem, but it is certainly better than slamming the door in their face with nothing more informative than “Error—please try again.”

Summary of Funnel Optimization

Presenting these findings to the client was groundbreaking. They had hired and fired several search engine marketing agencies in the belief that they were receiving poorly qualified leads, resulting in such a low (0.3 percent) conversion rate. In fact, the problem was entirely on their site: a poor user experience. Once the problem was fixed, their conversion rate jumped fourfold, with a concomitant revenue increase of millions of extra dollars per year. I should have billed by commission!

Funnel analysis shows both the power and the weakness of web analytics as a technique for understanding visitor behavior on your website. The power is in identifying the problem areas during a typical path visitors take; for that, your web analytics is capable of telling you what happened and when. That in turn enables you to focus your efforts on improving the particular problem page. The weakness of web analytics is that it does not tell you why visitors made the choices they did. To understand why visitors behave in an unanticipated way, you need to investigate—either directly yourself (try a checkout or booking on your own website) or by conducting a survey or usability experiment.

Tip: If usability experiments is a new term for you, don’t contact a specialist agency until you check out these excellent books by Steve Krug: Don’t Make Me Think (New Riders, 2006) and Rocket Surgery Made Easy (New Riders, 2010).

Measuring the Impact of Site Search

Site search is the internal search engine of your website that visitors often substitute for a menu navigation system. For large websites with hundreds or thousands of content pages (sometimes hundreds of thousands), internal search is a critical component for website visitors, enabling them to find what they are looking for quickly. Internal search engines generally use the same architecture as an external search engine such as Google. In fact, the major search engine companies sell their search technology to organizations. See, for example, the Google Search Appliance:

www.google.com/enterprise/search/gsa.html

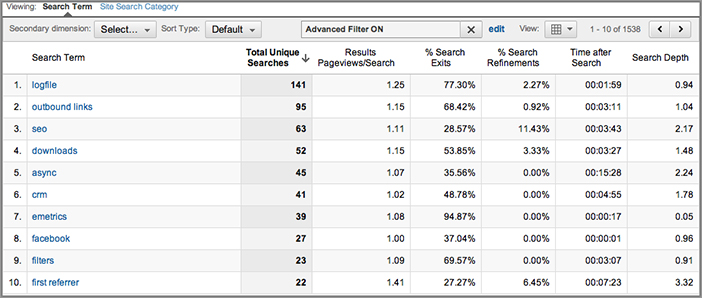

Important site search KPIs were discussed in the section “Webmaster KPI Examples” in Chapter 10. In addition to the Site Search Overview report (refer to Figure 10-25), one of the things you will want to know is what keywords visitors are typing once they arrive on your website. The idea is that once you know these keywords, you include them (or exclude them if they are not relevant to you) in your paid and organic campaigns as well as ensure that landing pages are optimized for them. This is discussed in the section “Optimizing Your Search Engine Marketing” later in this chapter. Example site search terms are shown in Figure 11-9, taken from the Content Site Search Search Terms report.

Figure 11-9: Site Search Terms report showing keywords used

Note: The value of the Site Search Terms report shown in Figure 11-9 should not be underestimated. Visitors on your website are actually telling you what they would like to see, in their own language, using their own terminology. Perhaps you assumed “widgets” was the commonly known name of your product, but you find out that people are searching for “gadgets,” or people are looking for “widgets with feature X,” which your manufacturing team hadn’t thought of. It’s analogous to your potential customers walking into your store or office and providing you with direct feedback—without you having to ask or worry about infringing on visitor privacy.

The Revenue Impact of Site Search

Beyond looking at site search terms used, how do visitors who use your site search facility compare to those who do not? I illustrate this with two screen shots taken from the Content Site Search Usage reports (Figure 11-10 and Figure 11-11).

Figure 11-10: Pages per visit comparison of visitors who use site search and visitors who do not

Figure 11-11: The per visit value difference from using site search

In Figure 11-10, you can see that the percentage of visits resulting in a site search is low at only 2.66 percent. However, the Pages/Visit metric for those visitors is almost five times higher compared to those who did not perform a search. Hence, a better user experience is inferred for those visitors.

Other key metrics can be selected from the drop-down list for comparison. A particular favorite of mine is the Per Visit Value (or Per Visit Goal Value if yours is a nontransactional site), as shown in Figure 11-11. For this metric to be available, ensure that you are in a Goal Set or E-commerce section of your reports—refer to label M of Figure 4-4 in Chapter 4 if needed.

Per visit values measure the value of a visitor. That is, did a visitor go on to complete a transaction or monetized goal? The higher the per visit value or per visit goal value for a visitor using site search, the more important that function is to the value of your website. I am assuming that where a visitor has come from, their referral source, is not a factor in whether they use site search or not.

From Figure 11-11, a visitor who uses site search is six times as valuable as a visitor who does not. For this example site, increasing the usage of the site search feature is clearly going to have a positive impact on the site. Armed with this information, meet with your web development team (those responsible for your internal site search engine) and discuss with them what plans they have for developing and growing the site search service. Before doing so, use the following formula to calculate the revenue impact that site search is having on your website:

Using Figure 11-11 and knowing the number of visitors who used site search for this example website (11,463, taken from the Site Search Overview report, not shown), the calculation is

revenue impact of site search = (1.32 – 0.22) × 11,463 = $12,609 per month

To put this value into context, it represents only 2.66 percent of the total traffic to the site. If site search participation can be increased, say to a around quarter of all visits, their value becomes $126,000 per month—a very significant amount. This may at first sound like an unbelievable target. However, I have achieved these types of gains with several e-commerce site search facilities.

What If Site Search Has a Negative Revenue Impact?

In the previous examples, site search was shown to be clearly beneficial for the site, but what if the metrics are reversed—that is, visitors who use site search have lower Per Visit and Per Visit Goal Values than those who don’t. This would result in a negative revenue impact of site search—its use is costing you money!

It is possible that such a result could be valid. That is, in some scenarios, finding information can best be served by a directory-type structure of navigation rather than a search engine—for example, a visitor looking for location-specific information or where jargon may be a barrier to know what to search for. However, I have found this to be rare.

Instead, a negative revenue impact of site search usually indicates an issue with the quality of the results returned. So far, we have assumed that your internal site search engine is working well, producing accurate and informative results regarding visitors’ searches—the visitor just needs to be encouraged to use it. Unfortunately, most often this is not the case. There can be two reasons for this to happen:

- Your site search cannot find content to match the visitor’s query.

- The results returned by your site search are of poor quality.

Other Metrics for Comparing the Performance of Site Search

Other key metrics can be selected from the drop-down list shown at the top of the table in Figure 11-1. These are as follows:

Goal Conversion Rate

Revenue

revenue = goal value + e-commerce value

Average Value

E-commerce Conversion Rate

Per Visit Value

To get a handle on whether the first reason is valid, look at the zero results produced by your site search engine. The method for tracking zero results is discussed in Chapter 8. Assuming you have used the same setup, select the label Zero from your Content Site Search Search Terms Category report. This reveals the keywords used that generated a zero result—as per Figure 11-12.

Figure 11-12: Viewing zero-result keywords from site search

Export this list into Excel, and highlight the keywords that are directly related to your website content. Meet with your web development team to ascertain why such relevant terms produce zero results. Maybe you have overlooked misspellings, regional differences (think “holiday” versus “vacation”), or visitors using terminology they are not familiar with. However, it may be that there is a problem with how your site search engine works or is configured. Is it picking up newly created or modified pages? Can it index PDF files? How is it ranking results?

Identifying the second reason—poor quality results returned by your site search—is harder to ascertain quantitatively. As discussed in Chapter 1, web analytics tools are great at telling you what happened on your website and when. But they cannot tell you why it happened. To understand the quality of a user’s experience, you need to either ask your visitors (deploy a feedback survey) or put yourself in your visitors’ shoes and go through the experience yourself. I recommend the latter method in the first instance—in fact, you should be regularly visiting your site to test the visitor experience.

Poor-quality results are indicated by a negative value, or a low value, of your revenue impact of site search combined with low frequency of zero results. This is the case when your site search returns irrelevant results, such as, for example, reams of press releases—useful for the media though not interesting for the vast majority of your visitors, or when site search returns product sales information when the visitor is looking for help and support information. Investigate this further by looking at the number of search exits (visitors who exit following a search) and search depth (the number of pages viewed after a search). Review the section “Webmaster KPI Examples” in Chapter 10 and in particular Figure 10-25 as needed.

A high search exit rate and low search depth are indicators of poor site search results. It may mean that the results are either irrelevant or are poorly ranked—too many results with a lower relevancy ranking higher. Perform the searches for your 10 most common keywords and judge for yourself. A simple fix is to allow your visitors to categorize their search requests. For example, using the previously mentioned scenarios, search only within the “product details,” “support information,” and “press releases” categories.

Summary of Site Search Impact

Site search engines are often installed and configured once and then forgotten—that’s a mistake. I often find the greatest opportunity for site improvement, that is, conversion and revenue improvement, is found by looking at its site search performance. Websites evolve rapidly, including new content and new technologies. If site search visitors have a lower revenue impact without good reason, then site search is costing you money. Present this figure to the head of your web team and schedule a meeting to discuss enhancements or a replacement. Showing a dollar amount is a much better motivator than saying, “Our site search is not working effectively.”

With your export list of zero-result site search terms, highlight the keywords visitors used that are not relevant to your organization but are related to the business you are in. If the number of these is significant (more than a few percent of the total number of unique searches), then meet with your product or service team to discuss their meaning. Perhaps the product team never thought people would want to search for feature X combined with product Y. Your site search data could provide valuable insight into this. For example, an action item may be to build a specific landing page for product XY to gain further feedback from those visitors.

Optimizing Your Search Engine Marketing

If you own a commercial website, then you want to drive as much qualified traffic to it as possible. Online marketing options include search engine optimization (nonpaid search, also known as organic search), paid search advertising (text ads, also referred to as pay-per-click or cost-per-click), email marketing, display advertising (banners), and social network participation (comments and links left on sites such as Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, forums, blogs, and so on).

All of these visitor acquisition methods have a cost—either direct with the media owner or indirect in management fees—though there is nothing stopping you as a do-it-yourself enthusiast. Optimizing your marketing campaigns using Google Analytics data can achieve cost savings and expose significant opportunities for your business. The following sections focus on the essential steps for optimizing your search engine marketing (SEM), both paid and nonpaid, including the following:

- Keyword discovery (paid and nonpaid search)

- Campaign optimization (paid search)

- Landing page optimization and SEO (paid and nonpaid search)

- AdWords day parting optimization (paid search)

- AdWords ad version optimization (paid search)

Keyword Discovery

When optimizing for SEM, one of the things you will constantly be on the lookout for is ideas for adding new, relevant keywords to your campaigns. These can be broad (for example, shoes), bringing in low-qualified visitors in the hope they will bookmark your page or remember your brand and website address for later use, or very specific (for example, blue suede shoes), which are highly targeted to one of your products and could lead to an immediate conversion on a visitor’s first visit.

Several offsite tools are available to help you conduct keyword research:

- Google AdWords Keyword Tool (https://adwords.google.com/select/KeywordToolExternal)

- Wordtracker (www.wordtracker.com)

These enable you to discover what people are searching for on the Web as a whole (hence the term offsite tool) that may be related to your products or services and in what numbers. The tools help you determine which search keywords are most frequently used by search engine visitors and then help you identify related keywords, synonyms, and misspellings that could also be useful to your marketing campaigns. Clearly, being language and region specific is important; for example, tap and holiday are terms used in the UK that in the United States are more commonly known as faucet and vacation, respectively.

Note: The differences between offsite and onsite web analytics are discussed in Chapter 1, “Why Understanding Your Web Traffic Is Important to Your Business.”

In addition to these offsite tools, your Google Analytics reports contain a wealth of onsite information that can help you hunt for additional suitable keywords. There are two areas to look at: search terms used by visitors to find your website from a search engine and internal site search queries, that is, those used by visitors within your website.

Farming from Organic Visitors

The Traffic Sources Sources Search Organic report is dedicated to referral keywords—keywords used by visitors who come from all organic search engines (see Figure 11-13). As an initial exercise, export all of your organic keywords. Compare them with those targeted by your paid campaigns from the Traffic Sources Sources Search Paid report. Organic terms that are not in your paid campaigns are excellent candidates to be added to your pay-per-click account. After all, you will wish to maximize your exposure to relevant search terms.

Figure 11-13: Keyword research from organic visitors

When adding keywords used by organic search visitors to your pay-per-click campaigns, consider your current organic search rankings for those terms. For example, if you are number one for your brand or product name in the organic results, should you also add this to your paid campaigns? If you do, you are likely to cannibalize your own free organic traffic.

My recommendation is to not bid if you have no pay-per-click competitors for a specific brand term (such as your company name)—otherwise you will be paying for traffic that will already come to you. On the other hand, if your competitors are bidding on your brand terms you should also bid on them, even with your number one organic ranking. The hypothesis is that you receive an additional boost in traffic (a 2 + 2 = 5 effect) by picking up traffic from your competitors. The additional traffic comes from pushing down your competitors’ ranking in the paid result and occupying more “shelf space” on the results page itself.

The screen shown in Figure 11-13 is an excellent example of the wealth of information readily available within reports for improving your SEO efforts. In this case I have selected the pivot view to show visits and bounce rates on a per-search-engine basis. The secondary dimension is also used to provide the landing page URL for each keyword. The result is a report of search engines (shown horizontally across the top of the data table) that correlates keywords with landing pages, showing bounce rate and visit metrics. This is information that will surely keep any marketer busy for several hours!

What Does the Keyword (Not Provided) Mean?

Row 4 in Figure 11-13 shows a keyword labeled “(not provided)”. This is the entry that Google sets when a visitor conducts a search on a Google property while they were logged into their Google account—for example, a Gmail user who is logged into their mail account and opens another window to perform a search.

Google’s reasoning for this is privacy—that is, users often access their email via open Wi-Fi networks, and their search query terms could contain personally identifiable information. When logged in to their Google account, the user’s search is encrypted and so not viewable over an open Wi-Fi connection. In October 2011, Google also made the decision to remove any referral keyword information transferred to a website when a user clicks through from a search result. Because the keyword information is removed, this affects all web analytics vendors.

Oddly, this setting does not affect visitors who click ads while logged in and conducting their search. For more discussion on this see

www.advanced-web-metrics.com/blog/2011/10/19/organic-search-terms-blocked-by-google

Farming from Site Search Visitors

If your site has an internal search engine to help visitors find what they are looking for, then this is an excellent feedback mechanism for your marketing department—that is, visitors telling you exactly what they want to see on your website. Your Content Site Search Search Terms report is a rich seam of invaluable keyword information for you to mine. We looked at measuring the success of site search in the preceding section and also in Chapter 10, in the section “Webmaster KPI Examples.”

From within your Google Analytics account, export your site search keywords and compare them with those in your paid search accounts (pay-per-click). Site search keywords not in your pay-per-click accounts are strong candidates to be added. As described for farming from organic search visitors, when selecting new keywords from your Site Search reports, also check your organic rankings for them. If you have a relevant landing page ranked as number one organically for a particular search engine and no pay-per-click competition for that term, I suggest that you do not add that term to your paid campaigns for that search engine. There is no point—you just cannibalize your own free organic traffic.

In addition to comparing keywords from site search with your paid campaigns, also compare them with your nonpaid search terms. Perhaps there are variations in usage or spelling you can take account of in your page content. Perhaps visitors are using relevant keywords after they are on your site that you are not aware of. For example, visitors looking for books may also use keywords such as “how-to guides,” “manuals,” “white papers,” and “tech sheets” on your internal site search. This is a perfect opportunity to build and optimize your website content for those additional, related terms.

Campaign Optimization (AdWords)

After farming for new keywords from organic search engines and site search users, and adding them to your paid campaigns (if applicable) and to the content of relevant pages, the next stage is to ensure that these keywords are optimized—that is, that they give you the best possible chance of conversion.

Within the Advertising side menu is a dedicated section for AdWords. This enables you to drill down into campaign, ad group, and keyword levels for details of conversion rates, return on investment (ROI), margin, and more. As a business entity, you want to invest more in campaigns that produce more conversions and leads for you than in those that merely create visibility for your brand. However, you must take care here because by default Google Analytics gives credit for a conversion to the last referrer. In other words, spending more on campaigns that are reported as generating conversions and culling those that don’t may result in you chopping off the head that feeds the tail.

The Multi-Channel Funnels report discussed in Chapter 5 enables you to see the path and interaction of different referral sources that lead to conversion. Therefore, it is important to refer to this report when optimizing all of your marketing efforts. This is discussed in “Attribution Optimization” later in this chapter.

Calculating Your Real ROI

The calculation performed by Google Analytics for the AdWords Return on Investment is very straightforward, as follows:

ROI = (revenue – cost) / cost

Therefore, if the ROI for a keyword is shown in your reports as 500 percent, this means you are receiving a $5 return for every $1 spent on AdWords. Assuming your revenue is $600 from $100 spent, this is calculated as follows:

However, Google Analytics has no idea what margins you operate under, so the default ROI displayed by Google Analytics is misleading. Figure 11-14 shows the default ROI on a per-keyword basis—available in the Clicks area of your reports in the Advertising AdWords Keywords section.

Figure 11-14: The ROI values of AdWords keywords

You will need to factor in your operating profit to get the true ROI figures. For example, assuming the same revenue and cost figures, if your profit margin (excluding marketing costs) is 40 percent, your real ROI is calculated as follows:

Table 11-1: Comparing ROIreal versus the reported ROI from Google Analytics

Table 11-1 illustrates the importance of taking into account your profit margins when interpreting your ROI values. While the trends will remain the same, the more accurate ROIreal values are important because they determine how much money you can bid for competitive terms in order to stay profitable. This is discussed next.

Note that when a keyword does not generate any revenue, its ROI and ROIreal values show as –100%.

Note: At the beginning of a campaign launch, your ROI may be negative as you build up brand awareness and visibility for your website. Visitors to a new website (new to them) usually require multiple visits before they convert. However, a negative ROI should be acceptable for only a short period of time—on the order of weeks, depending on your circumstances. See also Figure 10-6 in the section titled, “E-Commerce Manager KPI Examples,” in Chapter 10.

The ROI of Other PPC Networks

Within Google Analytics you can track visitors from any search engine, and any referral, right down to campaign and keyword levels. However, at present, cost data can only be imported from AdWords. That is, within your reports, ROI data can be calculated only for AdWords visitors. To perform the same calculations for other marketing channels, export your visit and revenue data to a spreadsheet and merge it with your third-party cost data.

Calculating Your Maximum Bid Amount

Your maximum bid (max bid) is the maximum amount you are prepared to pay for a keyword in the AdWords auction system. The actual amount you pay depends on many factors. For example, how many competitors are also bidding on the same keyword, how effective their ads are at gaining click-throughs, how effective your ads are at gaining click-throughs, how well you retain your visitors—that is, not bouncing them back to AdWords because your landing page failed to meet their expectations. These are the basis of the AdWords Quality Score system.

Being able to calculate your max bid is therefore an important aspect of your AdWords optimization. Your ROIreal determines the amount. That is, the ROIreal you wish to maintain while bidding will determine the max bid amount. The following is a detailed explanation. Unfortunately, describing the process on paper is cumbersome. However, in Excel the process is quite straightforward. I show this in the next section, “Simplifying the Task.”

First, select a ROIreal that you are comfortable with—that is, one that drives more traffic to your website while still providing a healthy profit margin for you. For an online retailer this may be 25 percent, for example (making $0.25 profit for every $1.00 spent). With your preferred ROIreal set, calculate the maximum amount this allows you to spend on customer acquisition—the maximum cost per acquisition (cpamax)—by using the following procedure:

For this example, I use the data for Keyword 1 from Table 11-1. Setting a target ROIreal of 25 percent and a profit margin of 40 percent, the calculation is as follows:

This is the total cost you are willing to pay for a visitor with keyword 1 in order to achieve an average order of $192.78. Of course, not every visitor who clicks your ad is going to become a customer, so knowing your conversion rate for each keyword, you calculate your maximum cost per click (cpcmax) allowed for that keyword. Here I use the e-commerce conversion rate for keyword 1 (0.8 percent), taken from the E-commerce section of the reports (the menu link adjacent to Clicks), though it is not shown.

For this example keyword, you could bid up to $0.49 in AdWords to generate as much traffic as possible and be assured that you will make a gross profit of $1.25 for every $1.00 spent. You will never overbid for your AdWords keywords—even if you reach your cpcmax within your AdWords account, you will still maintain a 125 percent ROIreal. Because the actual bid you pay in AdWords is determined by the market and is in constant flux, your ROIreal is likely to be higher than this for all but your most competitive keywords.

Tip: As you will have noticed from this exercise, the data you are accessing comes from two reports within your Advertising AdWords Keywords report—the Clicks and E-commerce reports. Clicking backward and forward between these is obviously cumbersome. Therefore, use the Better AdWords custom report as described in Chapter 9 to merge the relevant data points. One change is required to this custom report—change the dimension from campaign to AdWords keyword.

Note: If you are a nontransactional site, substitute Total Goal Value for Revenue, Per Visit Goal Value for Average Order Value, and Goal Conversion Rate for E-commerce Conversion Rate in the calculations. Your goals will need to be monetized for this to work—see Chapter 8.

Simplifying the Task

The calculations of cpcmax appear cumbersome when written on paper, but with a spreadsheet it is actually quite simple, as shown in Figure 11-15. First, you need to export your Advertising AdWords Keywords report. However, as explained in the previous tip, the data you require is in two reports—the Clicks and E-commerce reports. To make things easier for you, use the Better AdWords custom report as shown in Chapter 9. This allows you to have all the data in one report (you will need to change the dimension from campaign to AdWords keyword).

Figure 11-15: Excel spreadsheet to calculate per-keyword cpcmax

With the Better AdWords custom report loaded, export the data to a CSV file (or schedule a report email on a regular basis), and open the file in Excel. From this spreadsheet, you require only three columns of data: Keyword, Average Value, and E-commerce Conversion Rate; the rest can be discarded unless you are a nontransactional site—see the previous sidebar note about substituting goal values for transaction values. From the screen shown in Figure 11-15, inputting your profit margin (cell E2) and desired ROIreal (cell E3) will display the cpcmax (column F).

Note: You can download this Excel template from www.advanced-web-metrics.com/chapter11.

As you can see, the cpcmax calculation is at the keyword level throughout. However, if you are bidding on large volumes of keywords (I once reviewed an AdWords account with over a million bid terms!), it is more likely that you will be bidding a single cpc amount for groups of keywords—that is, ad groups. In that case, the more focused your ad groups are, the more accurate the cpcmax calculation will be.

Attribution Optimization

Multi-Channel Funnels reports are described in the section “Top Standard Reports” in Chapter 5. They allow you to view the entire referral path that visitors use when they convert—that is, not just the last click, as has been traditionally the case. An example of this is shown in Figure 11-16, taken from the Conversions Multi-Channel Funnels Top Conversion Paths report.

Figure 11-16: Top conversion paths report

Figure 11-16 shows referrers grouped into color-coded dimension named channels. These are analogous to referral mediums. The default view is to show the basic channel grouping path. This is an insightful report in itself. However, I encourage you to explore other channels, using the links at the top of the report table—for example, source path, campaign path, and keyword path.

Why Copy the Basic Channel Grouping Template?

The second menu item shown in the drop-down list in Figure 11-17 allows you to copy the existing template used for the basic channel grouping, which is the default display for the Conversions Multi-Channel Funnels Top Conversion Paths report. You will need to alter this template if the default report does not match your existing campaign tracking setup. For example, Google Analytics groups together all referrals where medium=email as the channel named Email. That is obviously correct, but perhaps in your campaign tracking you have set medium=e-mail, e-mail marketing, or e-post (Swedish). With the default template these will not be grouped together in the Email channel. To do so, copy the basic channel grouping and edit accordingly.

Other common edits to the default grouping include Feed and Social Network. For example, Feed is set to use medium=feed by default to detect visits from your RSS feed. Yet you may have custom-tagged your feed as something else—the section “Integrating with Feedburner” in Chapter 6, “Getting Started: Initial Setup,” describes how to do this. The channel Social Network is compiled using a list of over 150 social network sites, determined by Google. Although the list is extensive, you may have niche social sites you wish to include with Google’s list.

As your knowledge of Multi-Channel Funnels reports grows, you will want to go deeper into understanding the finer correlations that exist. To assist with this, you can create your own custom channel groupings—either from scratch or using an existing channel, as shown in Figure 11-17.

Figure 11-17: Creating your own custom channel grouping

A common custom channel grouping I recommend is to compare brand search terms and generic search terms—that is, search engine visitors who already know of your company or product names versus those who are unaware of you. Knowing what interaction exists between these search engine visits clearly impacts your digital marketing. Figure 11-18 shows an example custom channel grouping for this book’s website (advanced-web-metrics.com).

In Figure 11-18, I have used two rules—one using a regular expression to include my specific brand terms. These are brian|clifton|advanced web metrics|measuring success. The second rule is the inverse of this, the same regular expression match but with the condition set to exclude my brand terms; that is, every other keyword used by my visitors. You could be more specific here. For example, using “company brand” keywords, “product A brand” keywords, “product B brand” keywords, and so forth.

Figure 11-18: Custom channel grouping set up for search engine visitors using brand terms versus generic terms

The result of applying my custom channel grouping is the report shown in Figure 11-19. This has branded search terms color-coded as gold and nonbranded search terms color-coded as black and shows conversions where the referral path contains two or more referrals (the default view).

What is interesting to observe from Figure 11-19 is that 51 of 121 transactions have visitor interactions between brand and generic terms, accounting for 21 percent of the revenue. (Note that to illustrate the point, I have used only the data shown for the first 10 conversion paths for this calculation—not the full channel grouping contents of 149 rows).

Figure 11-19: Custom channel grouping report produced from Figure 11-18

As Figure 11-19 clearly shows a strong interaction between brand and nonbranded search terms, I recommend a further refinement of this method. That is, creating two additional custom channel groupings to differentiate between paid and organic search and between head terms and long-tail keyword terms. See Figure 11-20a and b, for example.

Figure 11-20: Refining your custom channel grouping: (a) differentiating paid versus organic terms and (b) differentiating organic head versus long-tail terms

Note: By head terms, I am referring to the key phrases you wish your site to be found for and that therefore should have the highest volume of visitors. By contrast, “long-tail” phrases are more specific and therefore individually generate less traffic. The sum of traffic from the long-tail phrases, however, can be very large—which is why they are important.

Landing Page Optimization and SEO

For search engine marketing, a landing page is defined as the page your visitors land on (arrive at) when they click through from a search engine results page. As such, landing pages need to be focused on the keywords your visitors have used—that is, keywords relevant to what they are looking for—and be as close to the conversion point as possible. That way, you give yourself the best possible chance of converting your visitors into customers.

For paid search, controlling which landing page a visitor arrives at is straightforward: You enter the URL in your pay-per-click campaigns. For example, in AdWords, each ad group can have its own unique landing page relevant to the displayed advertisement. For all paid search campaigns, you need to append tracking parameters to your URLs. This is done automatically for you in AdWords, but you must apply this manually for other paid networks (see “Campaign Tracking” in Chapter 7).

Robots.txt

Not all pages on your site are relevant to search engine visitors, such as, for example, your privacy policy or your mission statement to be carbon neutral by the end of this year. Although both are laudable, unless they are a key aspect of your business, consider removing such pages from the search engine indexes—the file robots.txt is used to do this.

The use of robots.txt stops search engines from indexing pages on your website. If you have an existing page indexed and you add it to your robots.txt file as an exclusion, then over time it will be removed from the indexes.

For example, create a text file in the root of your web space named robots.txt with the following contents:

User-agent: *

Disallow: /images/

Disallow: /offer_codeY.aspx

This file tells all search engines that follow the robots exclusion standard (all the main ones do) to not index any files in the directory named /images or the specific file named offer_codeY.aspx. For more information on the robots exclusion standard, see www.robotstxt.org.

For nonpaid search (organic search), controlling landing pages is much harder to achieve because search engines consider all pages on your website when deciding which are most relevant to a visitor’s search query. If you describe a product on multiple pages, then any or all of the pages may appear in the search engine results. However, the highest-ranked page may not be your best-converting page. By optimizing the content of your best-converting page, you can influence its position within the search engine results, thereby gaining a higher position than other related pages from your site. Landing page optimization is therefore a subset of search engine optimization (SEO).

Principles of SEO and Landing Page Optimization

For both paid and nonpaid search visitors, you want to ensure that the landing page is as effective as possible—optimized for conversion—once a visitor arrives. That does not mean the visitor’s next step is necessarily to convert from this initial landing page; the landing page could be the beginning of the relationship, with the conversion happening much later or on a subsequent visit. By optimizing the content of your landing pages for a better user experience, you not only increase conversions for all visitor types but also improve your organic search engine rankings. Often the effects of this optimization process can be dramatic.

A key part of the optimizing process is understanding why visitors landed on a particular page of your website in the first place. The keywords they used on the referring search engine tell you this. Within Google Analytics you can view keywords for your top landing pages in a couple of ways:

- From the Traffic Sources Sources Search section, select the Organic or Paid report to view the respective keywords from each. Click a keyword, and select Landing Page as the secondary dimension.

- From the Content Site Content Landing Pages report, click a landing page and select Keyword as the secondary dimension.

Generally I prefer the latter: focusing on a landing page and viewing which search keywords led visitors to it. This method is referrer agnostic, meaning you cannot tell whether your visitors arrived on a particular landing page by clicking an organic listing or a paid ad. This difference is not important; a visitor arriving on your website by a well-targeted link (paid or nonpaid) should be just as likely to convert regardless of the referrer used.

For the optimal user experience, focus your landing pages on a particular keyword theme, such as a specific product or service. The exception to this would be your home page, which shouldn’t be used as a landing page except for your company or brand name keywords.

Note: Your home page is generally poor as a landing page for anything other than your company name. This is simply because by its very nature your home page is a generalist page that focuses on creating the right image, branding, and mission statements. Usually you will notice low conversion rates for this page, which is expected. Therefore, focus your efforts on your content pages.

Keyword theme is a term used in search engine marketing to describe a collection of keywords that accurately describe the content of a page. For example, if you sell classic model cars, keyword themes would center on particular makes and models, such as the following:

classic alpha romeo model car

replica model alpha romeo

classic alpha romeo toy car

Less-product-specific pages—for example, a category page—would use a less-specific keyword theme:

model cars for purchase

classic toy cars for sale

scale model cars to buy

As a rule of thumb, themes generally consist of 5 to 10 phrases per page that overlap in keywords (the preceding examples list three such phrases for each page). Having more than 10 overlapping phrases dilutes the impact and effectiveness of the page, from the perspective of both the user experience and search engine ranking. If you already have a page that targets more than 10 keyword phrases, consider creating a separate page to cater to the additional keywords.

At this stage I am assuming you have been through the process described earlier in this chapter under the heading “Identify and Optimize Poor-Performing Pages.” If not, do this first because it ensures that the user experience for each page is optimized; improving the user experience often reaps large rewards. Then, as an exercise, view your top 10 landing pages from your Content Site Content Landing Pages report.

For each page listed in the report, click through and select Keyword as the secondary dimension. Print out the top 10 entrance keywords and repeat this process for each of your landing pages. Visit your website and print out each of your top 10 landing pages. That gives you your top 10 landing pages with a list of the top 10 keywords associated with each.

Note: If your Keywords report for each landing page contains hundreds of table rows, it may be because it is poorly focused or targeted. Also, check the landing page URLs specified in your paid campaigns. Are they pointing to the most appropriate pages? If not, change them accordingly.

For each landing page URL, view the two corresponding printouts. Is the page content tightly focused on its listed Entrance Keywords report? This is quite a subjective process, though as a guide, if you read the first three paragraphs (or approximately the first 200 words) of your landing page and you don’t come across every one of your top 10 entrance keywords, then the page can be said to be unfocused. The extent of this is relative to the percentage of missing entrance keywords from those first paragraphs; for example, three keywords missed and you can say your page is 70 percent focused.

If you determine that a landing page is unfocused, revise its content, ensuring that all 10 of your top target keywords are placed within the first 200 human-readable words (that is, not part of the HTML syntax). Pay particular attention to placing keywords in your paragraph headings—for example, assuming a target keyword of “blue widget,” use a heading of <h1>Our blue widget selection</h1>.

Use Text to Display Text—Not Images

Machine-readable text is text that can be selected within your browser and copied and pasted into another document or other application such as Word or TextPad. If you cannot do that, then the text is likely to be a rastered image (GIF, JPG, PNG, and so on) or in another embedded format such as Flash. Often, design agencies prefer the image format when referring to a product or company name so that nonstandard fonts and smoothing or special effects can be applied. However, it is doubtful this has any impact on conversions over plaintext—if images are necessary, use them elsewhere on your pages—not as a substitute for text.

For SEO rankings, machine-readable text is king. The inappropriate use of images or other embedded content as headings will be detrimental to your SEO efforts. Search engines ignore images for ranking purposes, and embedded objects such as Flash can be only partially indexed. To mitigate this, it is good practice to include an alt tag (alternative text attribute) for each image to improve the usefulness of your document for people who have reading disabilities. However, it has very little positive impact on search engine ranking. Therefore, where possible, use HTML and CSS to style your text because these are the right tools for the job. Use images to display pictures and Flash for movie or animation effects.

Other prominent areas where you should place your target keywords that are not visible on the page include the title tag and description metatag. Using the same keyword examples, these could be written as follows:

<title>Purchase blue widgets from ACME Corp</title> <meta name="description" content=" ACME Corp, the blue widgets division of BigCorp, is a US sales and support channel for the industry-leading blue widget package." />

Page title tags are visible by reading the text in the title bar at the top of your browser (usually blue in Windows, silver on a Mac), but visitors generally do not read this on your page because it is located above the browser menu and navigation buttons—separately from your content. However, the title tag is the same text that is listed as the clickable link on search engine results pages and is therefore very, very (deliberate double emphasis) important for SEO ranking purposes. Ensure that each page has a unique title and description tag relevant to its content, with its most important keywords included.

A best practice tip is to also include your target keywords within call-to-action statements and make them hyperlinks to the beginning of a goal process—an Add to Cart page, for example. This is illustrated with the following text examples (the hyperlink text is underlined italic):

Bad SEO example To purchase and get a free gift click here.

Good SEO example Purchase blue widgets and get a free gift with your first order.

The second example contains three important elements that have proven to be many times more effective than the first (see “An Introduction to Google Website Optimizer,” later in the chapter, for ways to test this hypothesis):

- The call-to-action statement contains the target keywords.

- The call-to-action keywords are highlighted as a hyperlink.

- The hyperlink takes the visitor to the start of the goal conversion process.

The techniques described here for optimizing and focusing your landing pages will undoubtedly increase your conversion rates and decrease page bounce rates regardless of visitor referral source. In addition, as a consequence of improving the user experience, such changes also have a significant and positive impact on your search engine rankings. Therefore, once you have optimized the top 10 landing pages, move on to the next 10.

From a paid search point of view, you need to ensure that campaigns point to one of these optimized landing pages—or create new ones. The worst possible thing you can do is use your home page as the landing page. If you take away only one lesson from this section, it should be to avoid this mistake!

A Note on SEO Ethics

When optimizing your landing pages to place keyword phrases in more prominent positions, always consider the user experience. Overly repeating keywords or attempting to hide them (using CSS or matching against the background color, for example), though not illegal, will inevitably result in your entire website being penalized in ranking and possibly removed from search engine indexes altogether—and this can happen at any time without warning, even years later.

Although it is possible to get back into the search engine indexes once you have removed the offending code, this can be a long, drawn-out process that damages your reputation. Essentially, spamming the search engines is not going to win you any friends, either from your visitors or the search engines themselves, so avoid it.

Summary of Landing Page Optimization and SEO Techniques

Optimizing landing pages for better performance is a complicated business; indeed, it’s a specialized branch of marketing. However, here is a 10-point summary for you to follow that will give you a solid start:

- Always put your visitors and customers first; design for them, not search engine robots.

- Use dedicated landing pages for your campaigns, for both paid and nonpaid visitors.

- Ensure that landing pages are close to the call to action.

- Structure your landing page content around keyword themes of 5 to 10 overlapping keywords and phrases.

- Place your keyword-rich content near the top of the page, that is, within the first 200 words. Think like a journalist writing for a newspaper, with structured titles, headings, and subheadings that contain keywords.

- Use keywords in your HTML <title> tags.

- Use keywords in your anchor links—that is, HTML <a> tags.

- Avoid placing text in images or Flash or other embedded content.

- Use a robots.txt file to control what pages are indexed by search engines.

- Never “keyword stuff” or attempt to spam the search engines; it’s not worth it, and you can achieve better results by legitimate means.

If you have completed all 10 steps and are still thirsting for improvement (pages can always be improved), consider testing alternative page elements, as discussed in “An Introduction to Google Website Optimizer” later in this chapter.

Note: It’s important to recognize that I have attempted to cover only the principles of SEO. Many factors affect your search engine rankings. The more important ones are page content (keyword density, keyword prominence), site architecture, internal link structure, and the number and quality of incoming links from other websites—including social network sites. For further in-depth reading on the subject, see Search Engine Optimization (SEO) Best Practice Guide by Jake Hird et al. (Econsultancy, 2011); Search Engine Marketing, Inc.: Driving Search Traffic to Your Company’s Web Site by Bill Hunt and Mike Moran (IBM Press, 2008); and Search Engine Optimization: An Hour a Day, by Jennifer Grappone and Gradiva Couzin (Wiley, 2011).

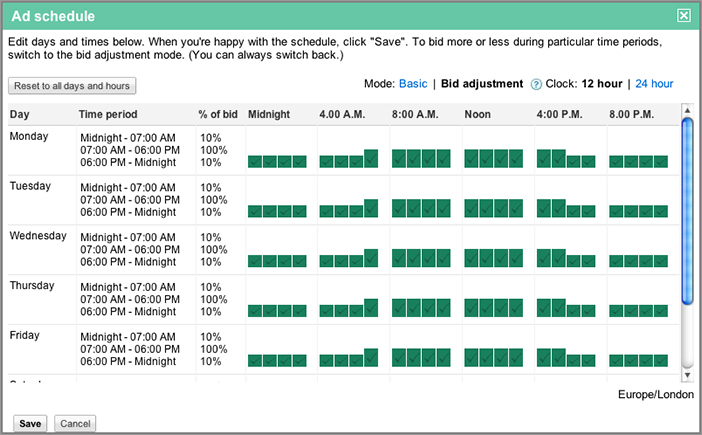

AdWords Day Parting Optimization

By knowing at what time of day visitors are accessing your website, you can better tailor your advertising campaigns to match. For example, if you are a business-to-business website, then most of your visits will probably occur during normal working hours. Rather than display your ads in equal distribution throughout the day, it would make sense to run and maximize your pay-per-click campaigns at around the same time your potential audience is looking on the Web.

Other examples of day parting optimization include targeting magazine readers, who are likely to be online in the early evenings; targeting social networking sites, whose potential audience is most likely to be online from 5:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m.; and coinciding with radio and TV advertisements, where remembering your website URL can be difficult and so the interested audience may subsequently conduct a search to find your site.

By viewing hourly reports, you can view the distribution of your visitors throughout the day. Hourly visitor reports are available in the Advertising AdWords Day Parts report (see Figure 11-21). Of course, time zones should be taken into consideration. For example, if your audience is global, ensure that your reports are first segmented by location—a proxy for time zone.

As with all data analysis, it is important to avoid looking at short time frames such as a single day. Visitors over short periods can vary significantly and randomly, making reports difficult (if not impossible) to interpret. Instead, select a longer period and ensure that the date range includes relevant days of the week for you. For a business-to-business website, for example, select Monday to Friday, or use Friday to Sunday if your target audience is more likely to be looking for your products or services in their leisure time. In addition, try to choose a discrete day range—one that does not overlap with national holidays if that would affect your visitor numbers. Whatever business you are in, also compare weekend visitors to weekday visitors because this can reveal surprising insights.

Figure 11-21: Viewing hourly reports for day parting optimization

From Figure 11-21, which is a business-to-business website with no day parting optimization, you can see that there are very few visitors in the early morning (midnight until 7:00 a.m.), significant numbers climbing to a peak just before lunchtime, a large drop during lunch, and then a steady decline in traffic until the end of the working day around 6:00 p.m. If you have e-commerce reporting enabled, also compare your day parting visitor information with when transactions take place: Go to the E-commerce section (refer to label M of Figure 4-4 to locate this).