Euclidean Constructions

According to tradition, it was Plato (ca. 427–347 BCE) who decreed that all geometric constructions should be done with a straightedge (an unmarked ruler) and compass alone. Of course, there is nothing intrinsically special about these tools, except perhaps their simplicity (you can still get them for a dollar or two at any drugstore), but Plato made their use into an art. Hundreds of constructions can be done with them, from very basic drawings to highly complex designs. Indeed, straightedge and compass constructions became so fundamental to geometry that Euclid incorporated them in his Elements from the very beginning. Proposition 1 of Book I—the very first of the 465 theorems in his Elements—shows us how to construct an equilateral triangle when its side is given. It is the same construction that generations of students have learned in their geometry class:

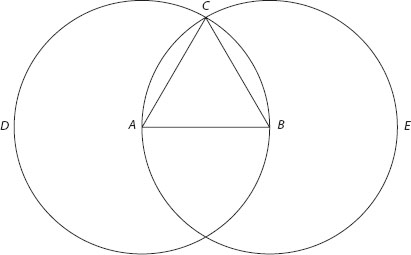

Let the given side be line segment ![]() (figure 18.1). With A as center, draw circle BCD. With B as center, draw circle ACE. The two circles meet at C. Now join C with A and with B. We have

(figure 18.1). With A as center, draw circle BCD. With B as center, draw circle ACE. The two circles meet at C. Now join C with A and with B. We have ![]() ; therefore,

; therefore, ![]() , proving that the required triangle is indeed equilateral.

, proving that the required triangle is indeed equilateral.

Figure 18.1

We should note that Euclid’s compass was different from the familiar modern compass: it “collapsed” when lifted from the paper and, therefore, could not be used to transfer line segments from one place to another. We do not know whether Euclid actually used it as a physical tool or whether he intended it merely as an abstract device with which one could do the construction in principle. Whichever the case, constructions with the straightedge and compass—jointly known as the Euclidean tools—became the subject of endless fascination, “a geometric solitaire which over the ages has attracted hosts of players, and though now well over two thousand years old, has lost none of its singular charm and appeal.”1

In fact, you don’t even need a straightedge. As the Danish geometer Jørgen Mohr (1640–1697) proved in 1672, every construction that can be done with a straightedge and compass can be done with a compass alone—provided you think of a line as given by the two intersection points of a pair of circles. Because Mohr published his result in Danish rather than Latin—the language of scientific discourse at the time—it received little attention until it was rediscovered in 1797 by the Italian Lorenzo Mascheroni (1750–1800). It was only by a curious incident that Mohr’s original theorem came to light, when a young mathematics student found a copy of his work in a secondhand bookstore in Copenhagen.

The result is now known as the Mohr-Mascheroni theorem.

By itself, a geometric construction is a stark, black-and-white array of lines and circles. But add color to it, and it can become an exquisite work or art, as plate 18, Seven Circles a Flower Maketh, shows. In the coming chapters we will look at some particular constructions, among them the regular pentagon.

NOTE:

1. The quote is from Howard Eves, A Survey of Geometry, p. 154. It might be supposed that the modern compass, being capable of transferring distances, can do more than its collapsible predecessor, but this is not the case: it can be shown that the two are completely equivalent in the sense that each can do everything the other can, although perhaps requiring more steps. For a proof, see Eves, p. 155.