Thales of Miletus

Thales (ca. 624–546 BCE) was the first of the long line of mathematicians of ancient Greece that would continue for nearly a thousand years. As with most of the early Greek sages, we know very little about his life; what we do know was written several centuries after he died, making it difficult to distinguish fact from fiction. He was born in the town of Miletus, on the west coast of Asia Minor (modern Turkey). At a young age he toured the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, spending several years in Egypt and absorbing all that their priests could teach him.

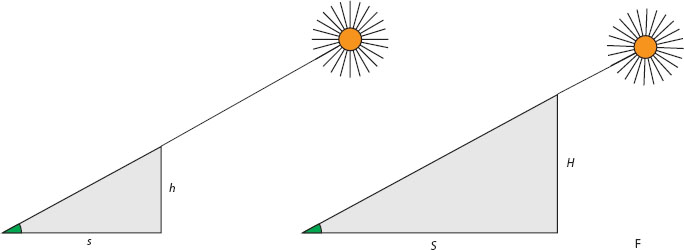

While in Egypt, Thales calculated the height of the Great Cheops pyramid, a feat that must have left a deep impression on the locals. He did this by planting a staff into the ground and comparing the length of its shadow to that cast by the pyramid. Thales knew that the pyramid, the staff, and their shadows form two similar right triangles. Let us denote by H and h the heights of the pyramid and the staff, respectively, and by S and s the lengths of their shadows (see figure 1.1). We then have the simple equation H/S = h/s, allowing Thales to find the value of H from the known values of S, s, and h. This feat so impressed Thales’s fellow citizens back home that they recognized him as one of the Seven Wise Men of Greece.

Mathematics was already quite advanced during Thales’s time, but it was entirely a practical science, aimed at devising formulas for solving a host of financial, commercial, and engineering problems. Thales was the first to ask not only how a particular problem can be solved, but why. Not willing to accept facts at face value, he attempted to prove them from fundamental principles. For example, he is credited with demonstrating that the two base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal, as are the two vertical angles formed by a pair of intersecting lines. He also showed that the diameter of a circle cuts it into two equal parts, perhaps by folding over the two halves and observing that they exactly overlapped. His proofs may not stand up to modern standards, but they were a first step toward the kind of deductive mathematics in which the Greeks would excel.

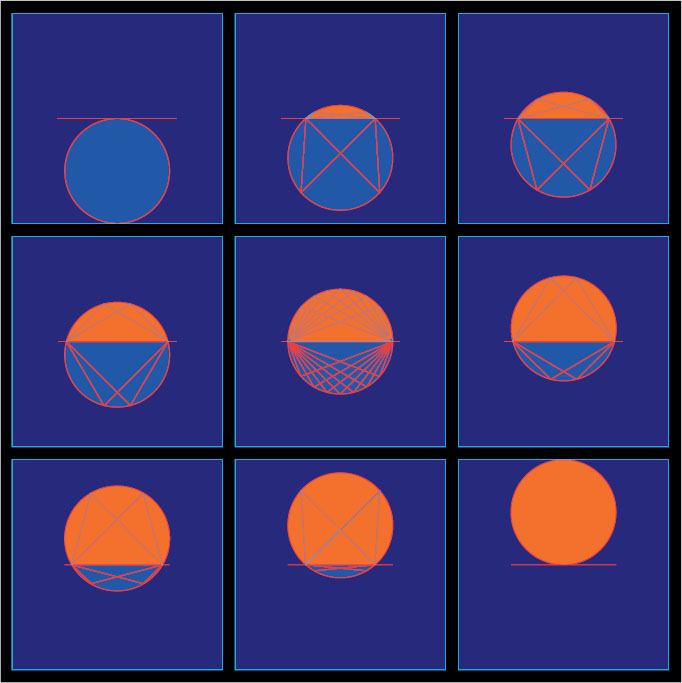

Thales’s most famous discovery, still named after him, says that from any point on the circumference of a circle, the diameter always subtends a right angle. This was perhaps the first known invariance theorem—the fact that in a geometric configuration, some quantities remain the same even as others are changing. Many more invariance theorems would be discovered in the centuries after Thales; we will meet some of them in the following chapters.

Thales’s theorem can actually be generalized to any chord, not just the diameter. Such a chord divides the circle into two unequal arcs. Any point lying on the larger of these arcs subtends the chord at a constant angle α < 90°; any point on the smaller arc subtends it at an angle β = 180° – α > 90°.1 Plate 1, Sunrise over Miletus, shows this in vivid color.

NOTE:

1. The converse of Thales’s theorem is also true: the locus of all points from which a given line segment subtends a constant angle is an arc of a circle having the line segment as chord. In particular, if the angle is 90°, the locus is a full circle with the chord as diameter.